The New York-based artist Matthew Day Jackson takes mixed media seriously. Behind the techniques and materials, the molten lead and the axe handles, the T-shirts and laser-etched Formica, Jackson’s aesthetic sees the world not as a continuum but as a mass of odd juxtapositions. Since his first big solo show in 2004, he has intertwined the grotesque and the beautiful. Every ten years, he paints a picture of himself as a corpse, but the majority of his work is mischievous, holding the autobiographical and the cerebral in an uneasy balance.

Hauser and Wirth, an international gallery with a strong educational remit, regularly brings its spikier artists to its property in Bruton, Somerset, to stay, work and reflect. The residencies come without strings, there are no prescribed outcomes, and one suspects there’s a certain mischief in who gets chosen. First to arrive, in 2014, was the (intermittently scary) video artist Pipilotti Rist. Seduced by her surroundings, she came up with sensuously observed close-ups of bodies and leaves in intimate proximity. Nothing wrong with that, of course. But it’s a risk for the gallery, and a challenge for the artists who stay here, that the landscape round about is so ridiculously seductive.

Showing next door to Matthew Day Jackson, Eve, an exhibition of paintings by the Somerset-based artist Catherine Goodman, is unashamedly paradisal. Even its edge of Freudian melancholy proves heartwarming in the end.

What on earth will Jackson, a cerebral city-dwelling proponent of an aesthetic he dubs the “horriful”, do with all this serried loveliness? He says that at first he found the landscape hard to read. “It’s more like urban space”, he says. “Everywhere you look, you can trace how humans have engaged with this place.” He can’t get over the time-worn depth of the lanes here. There’s no equivalent back home: “Maybe in Oregon and Wyoming, you can find tracks still rutted by wagon wheels”.

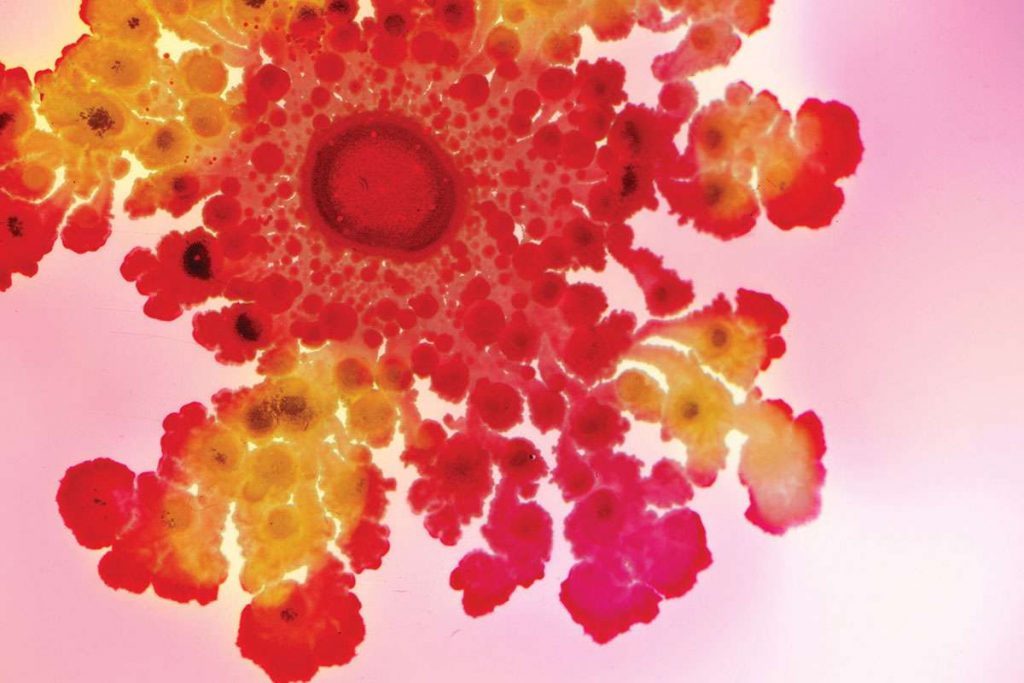

Predictably, for an artist who’s spent his career mapping the failures of American utopianism, Jackson has responded to the beauty around him by mourning its passing. His Solipsist collage-paintings of silk-screened Formica zoom out to encompass large swathes of the planet. Seen from various orbital viewpoints (the images are based on photographs taken by NASA astronauts) four elements emerge. Mine workings strip the Earth back to, well, its earth. The hopelessly polluted Ganges and the virtually vanished Ural Sea stand for water. Smoke plumes from forest fires give a shape to air. Yellowstone Lake inhabits a caldera that, if it erupted, would consume most life on Earth.

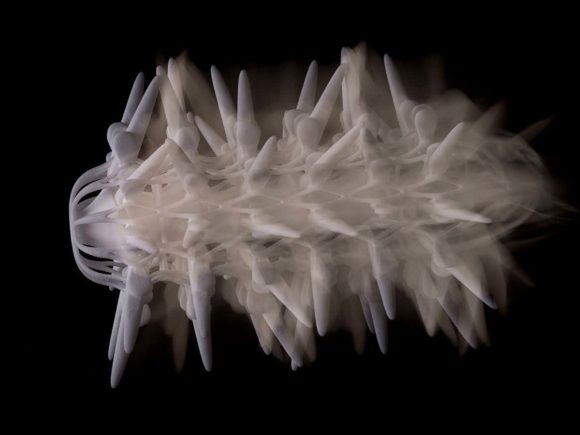

Each landscape, weirdly colourized (“Formica limits your colour palette”), laser etched with precise contours and subtle, uninterpretable boundary lines, resembles a computer-readable map. “Over” it (or, to be literal about this, embedded in it) is the flattened image of a satellite, made of cast lead.

The fact that the satellite observing the view is itself melted into the picture suggests a colossal foreshortening. There’s something suggestive of Jean Dubuffet, too, in the way the texture of the satellite is employed to convey a radical flatness. There’s no shade here, no occlusion, no hint of curvature. Human activity and human destiny are being measured and metricized to the point where even the planet has nowhere to turn.

Jackson’s flower paintings in the next room continue the theme: vases of hallucinatory Formica and fabric blooms, backlit by unearthly aurorae that may reference the tie-dye fad of the early 1970s but are more likely – given the way this show is going – something ghastly to do with nuclear testing.

The paintings work with the Astroturf floor and Jackson’s experimental, sculptural furniture to explore the idea that we only ever see things through their use. This isn’t a human foible: living things generally only sense what is relevant to their survival. So if Jackson is holding humanity to account here, it is a gentle and considered judgement. “What we most want is to feel that we exist”, he says, as we contemplate vanished seas and shredded mountain ranges. “We want not be lonely. Hence the appeal of metrics: they give us a sense of accomplishment.”

It can be a nuisance, having the artist around when you’re viewing a show. I was initially thinking about our greed and rapacity, and now, looking at these spoiled and garishly mapped earths, all I can see is our pathos: how we are polishing our rock down to the granite, just so we can glimpse ourselves in it.

Pathetic Fallacy is a well-chosen title for this show. John Ruskin coined the phrase to have a dig at the emotional falsity of poets who made clouds weep and trees groan. Jackson’s show is more in the spirit of Wordsworth’s defence of the practice, arguing that “objects . . . derive their influence not from properties inherent in them . . . but from such as are bestowed upon them by the minds of those who are conversant with or affected by these objects”.

In other words, we impose ourselves on the world because we feel we are the only meaning makers. On the way out, I pass more pictures: flattened lead satellites, cast in moulds made of corrugated cardboard, twine, sawdust, glue. This close, they appear slightly fleshy, slightly scabby, cast adrift, and travelling out into space.