Watching Brian and Charles, directed by Jim Archer, for New Scientist, 6 July 2022

Amateur inventor Brian Gittins has been having a bad time. He’s painfully shy, living alone, and has become a favourite target of the town bully Eddie Tomington (Jamie Michie).

He finds some consolation in his “inventions pantry” (“a cowshed, really”), from which emerges one ludicrously misconceived invention after another. His heart is in the right place; his tricycle-powered “flying cuckoo clock”, for instance, is meant as a service to the whole village. People would simply have to look up to tell the time.

Unfortunately, Brian’s invention is already on fire.

Picking through the leavings of fly-tippers one day, the ever-manic loner finds the head of a shop mannequin — and grows still. The next day he sets about building something just for himself: a robot to keep him company as he grows ever more graceless, ever more brittle, ever more alone.

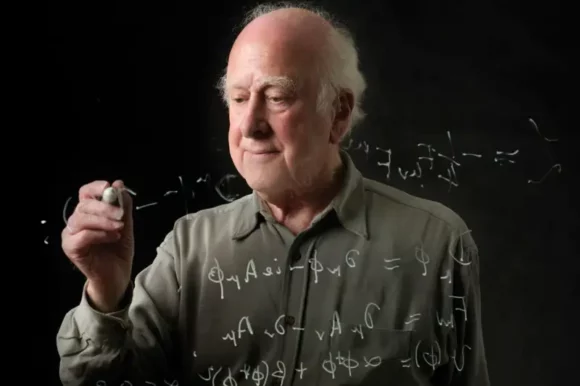

Brian Gittins sprang to life on the stand-up and vlogging circuit trodden by his creator, comedian and actor David Earl. Earl’s best known for playing Kevin Twine in Ricky Gervais’s sit-com Derek, and for smaller roles in other Gervais projects including Extras and After Life. And never mind the eight-foot tall robot: Earl’s Brian Gittins dominates this gentle, fantastical film. His every grin to camera, whenever an invention fails or misbehaves or underwhelms, is a suppressed cry of pain. His every command to his miraculous robot (“Charles Petrescu” — the robot has named himself) drips with underconfidence and a conviction of future failure. Brian is a painfully, almost unwatchably weak man. But his fortunes are about to turn.

The robot Charles (mannequin head; washing machine torso; tweeds from a Kenneth Clark documentary) also saw first light on the comedy circuit. Around 2016 Rupert Majendie, a producer who likes to play around with voice-generating software, phoned up Earl’s internet radio show (best forgotten, according to Earl; “just awful”) and the pair started riffing in character: Brian, meet Charles.

Then there were three: Earl’s fellow stand-up Chris Hayward inhabited Charles’s cardboard body; Earl played Brian, Charles’s foil and straight-man; meanwhile Majendie sat at the back of the venue (pubs and msuic venues; also London’s Soho Theatre) with his laptop, providing Charles’s voice. This is Brian and Charles’s first full-length film outing, and it was a hit with the audience at this year’s Sundance Film Festival.

In this low-budget mockumentary, directed by Jim Archer, a thunderstorm brings Brian’s robot to life. Brian wants to keep his creation all to himself. In the end, though, his irrepressible robot attracts the attention of Tomington family, his brutish and malign neighbours, who seem to have the entire valley under their thumb. Charles passes at lightning speed through all the stages of childhood (“Does it all stop at the tree?” he wonders, staring over Brian’s wall at the rainswept valleys of north Wales) and is now determined to make his own way to Honolulu — a place he’s glimpsed on a travel programme, but can never pronounce. It’s a decision that draws him Charles out from under Brian’s protection and, ineluctably, into servitude on the Tomingtons’ farm.

But the experience of bringing up Charles has changed Brian, too. He no longer feels alone. He has a stake in something now. He has, quite unwittingly, become a father. The confrontation and crisis that follow are as satisfying and tear-jerking as they are predictable.

Any robot adaptable enough to offer a human worthwhile companionship must, by definition, be considered a person, and be treated us such, or we would be no better than slave-owners. Brian is a graceless and bullying creator at first, but the more his robot proves a worthy companion, the more Brian’s behaviour matures in response. This is Margery Williams’s 1922 children’s story The Velveteen Rabbit in reverse: here, it’s not the toy that needs to become real; it’s Brian, the toy’s human owner.

And this, I think, is the exciting thing about personal robots: not that they could make our lives easier, or more convenient, but that their existence would challenge us to become better people.