Longing for the Bomb: Oak Ridge and atomic nostalgia, Lindsey A. Freeman (University of North Carolina Press)

Seeing Green: The use and abuse of American environmental images, Finis Dunaway (Chicago University Press)

for New Scientist (4 April 2015),

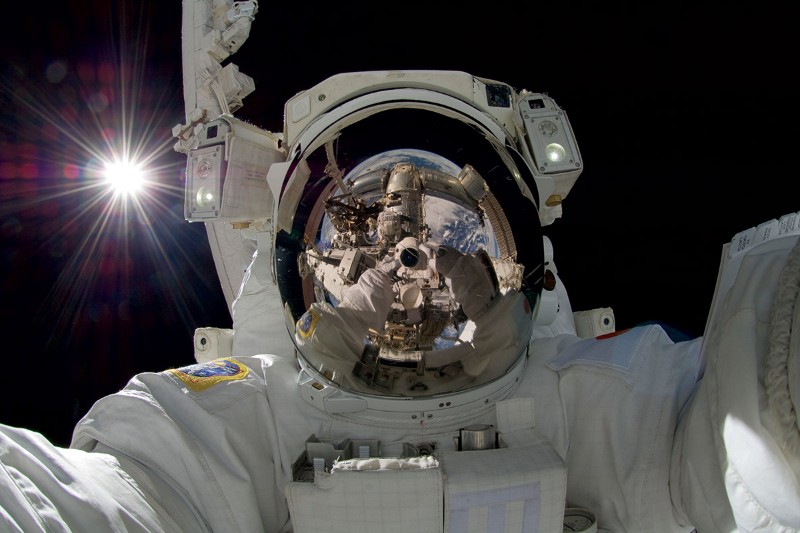

THE past can’t be re-experienced. It leaves only traces and artefacts, which we constantly shuffle, sort, discard and recover, in an obsessive effort to recall where we have come from. This is as true of societies as it is of individuals.

Lindsey Freeman, an assistant professor of sociology at the State University of New York, Buffalo, is the grandchild of first-generation residents of Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Once a “secret city”, where uranium was enriched for the US’s Manhattan Project, Oak Ridge opened its gates to the world in 1949 as America’s first “Atomic City”: a post-war utopia of universal healthcare, zero unemployment and state-owned housing.

In Longing for the Bomb, Freeman describes how residents of Oak Ridge dreamed up an identity for themselves as a new breed of American pioneer. He visits Oak Ridge’s Y-12 National Security Complex (an “American Uranium Center of Excellence”) during its Secret City Festival, boards its Scenic Excursion Train and cannot decide if converting a uranium processing site into a wildlife reserve is good or bad.

It would have been easy to turn the Oak Ridge story into something sinister, but Freeman is too generous a writer for that. Oak Ridge owes its existence to the geopolitical business of mass destruction, but its people have created stories that keep them a proud and happy community. Local trumps global, every time.

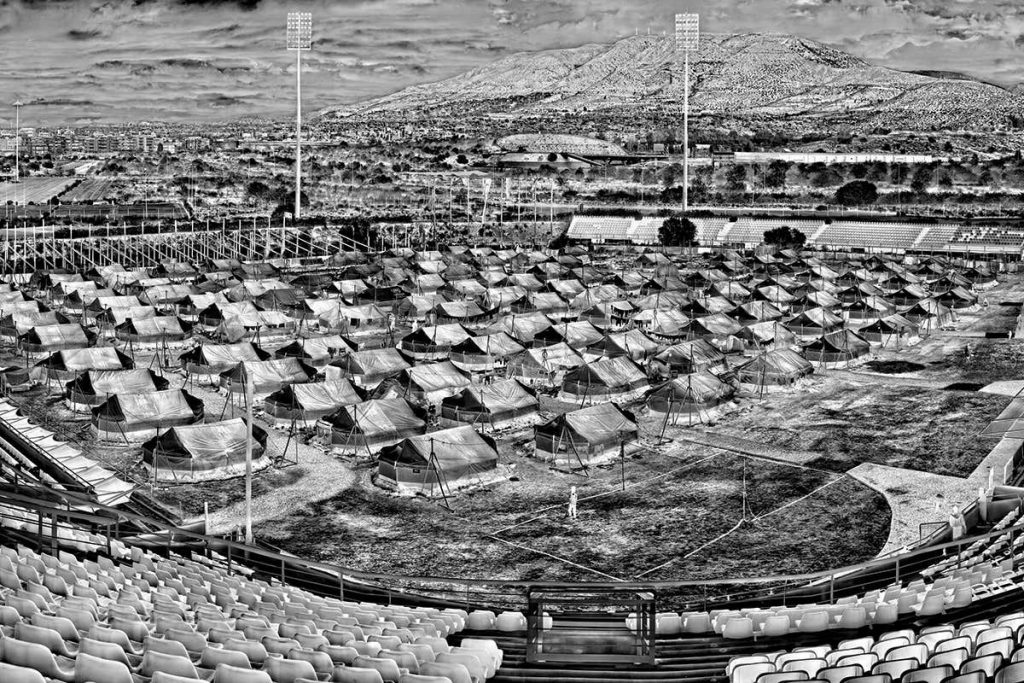

This is good for the founders of communities, but a problem for those who want to wake up those communities to the need for change. As historian Finis Dunaway puts it in Seeing Green, his history of environmental imagery, “even as media images have made the environmental crisis visible to a mass public, they often have masked systemic causes and ignored structural inequalities”.

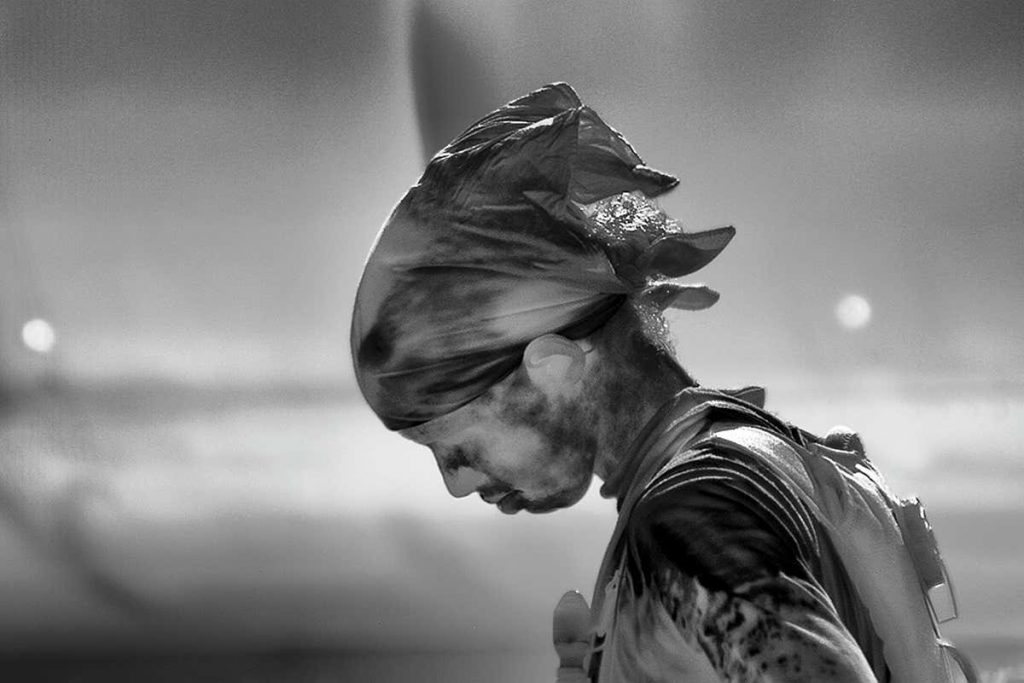

Reading this, I was reminded of a talk by author Andrew Blackwell, where he told us just how hard it is to take authentic pictures of some of the world’s most polluted places. Systemic problems do not photograph well. Some manipulation is unavoidable.

Dunaway knows this. Three months after the nuclear accident at Three Mile Island in 1979, the worst radioactive spill in US history occurred near Church Rock, New Mexico, on lands held by the Navajo nation. It took a week for the event to be reported, once, on a single news channel.

The remoteness of the site and a lack of national interest in Native American affairs might explain the silence but, as Dunaway points out, the absence of an iconic and photogenic cooling tower can’t have helped.

The iconic environmental images Dunaway discusses are essentially advertisements, and adverts address individuals. They assume that radical social change will catch on like any other consumer good. For example, the film An Inconvenient Truth, chock full of eye-catching images, is the acme of the sincere advertiser’s art, and its maker, former US vice-president and environmental campaigner Al Gore, is a vocal proponent of carbon offset and other market initiatives.

Dunaway, though, argues that you cannot market radical social action. For him, the moral seems to be that sometimes, you just have to give the order – as Franklin Roosevelt did when he made Oak Ridge a city.