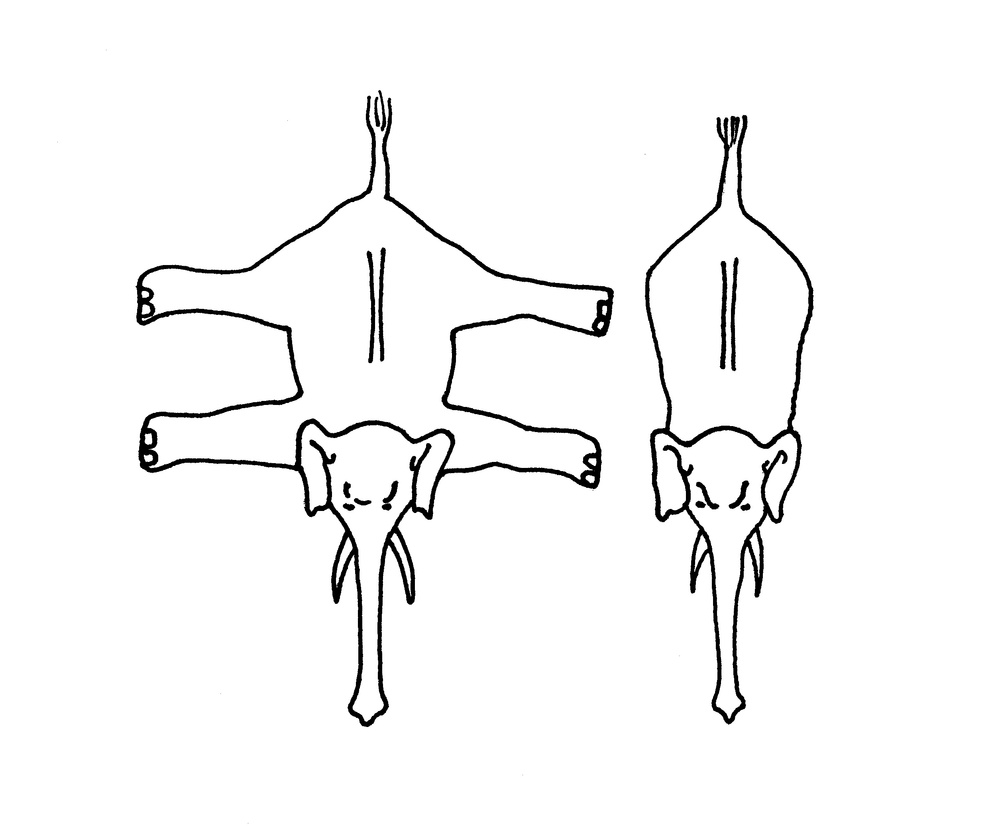

On paper, Pierre Huyghe’s new exhibition at the Serpentine Gallery in London is a rather Spartan effort. Gone are the fictional characters, the films, the drawings; the collaborative manga flim-flam of No Ghost Just a Shell; the nested, we’re not-in-Kansas-any-more fictions, meta-fictions and crypto-documentaries of Streamside Day Follies. In place of Huyghe’s usual stage blarney come five large LED screens. Each displays a picture that, as we watch, shivers through countless mutations, teetering between snapshot clarity and monumental abstraction. One display is meaty; another, vaguely nautical. A third occupies a discomforting interzone between elephant and milk bottle.

Huyghe has not abandoned all his old habits. There are smells (suggesting animal and machine worlds), sounds (derived from brain-scan data, but which sound oddly domestic: was that not a knife-drawer being tidied?) and a great many flies. Their random movements cause the five monumental screens to pause and stutter, and this is a canny move, because without that arbitrary grammar, Huyghe’s barrage of visual transformations would overwhelm us, rather than excite us. There is, in short, more going on here than meets the eye. But that, of course, is true of everywhere: the show’s title nods to the notion of “Umwelt” coined by the zoologist Jacob von Uexküll in 1909, when he proposed that the significant world of an animal was the sum of things to which it responds, the rest going by virtually unnoticed. Huyghe’s speculations about machine intelligence are bringing this story up to date.

That UUmwelt turns out to be a show of great beauty as well; that the gallery-goer emerges from this most abstruse of high-tech shows with a re-invigorated appetite for the arch-traditional business of putting paint on canvas: that the gallery-goer does all the work, yet leaves feeling exhilarated, not exploited — all this is going to require some explanation.

To begin at the beginning, then: Yukiyasu Kamitani , who works at Kyoto University in Japan, made headlines in 2012 when he fed the data from fMRI brain scans of sleeping subjects into neural networks. These computer systems eventually succeeded in capturing shadowy images of his volunteers’ dreams. Since then his lab has been teaching computers to see inside people’s heads. It’s not there yet, but there are interesting blossoms to be plucked along the way.

UUmwelt is one of these blossoms. A recursive neural net has been shown about a million pictures, alongside accompanying fMRI data gathered from a human observer. Next, the neural net has been handed some raw fMRI data, and told to recreate the picture the volunteer was looking at.

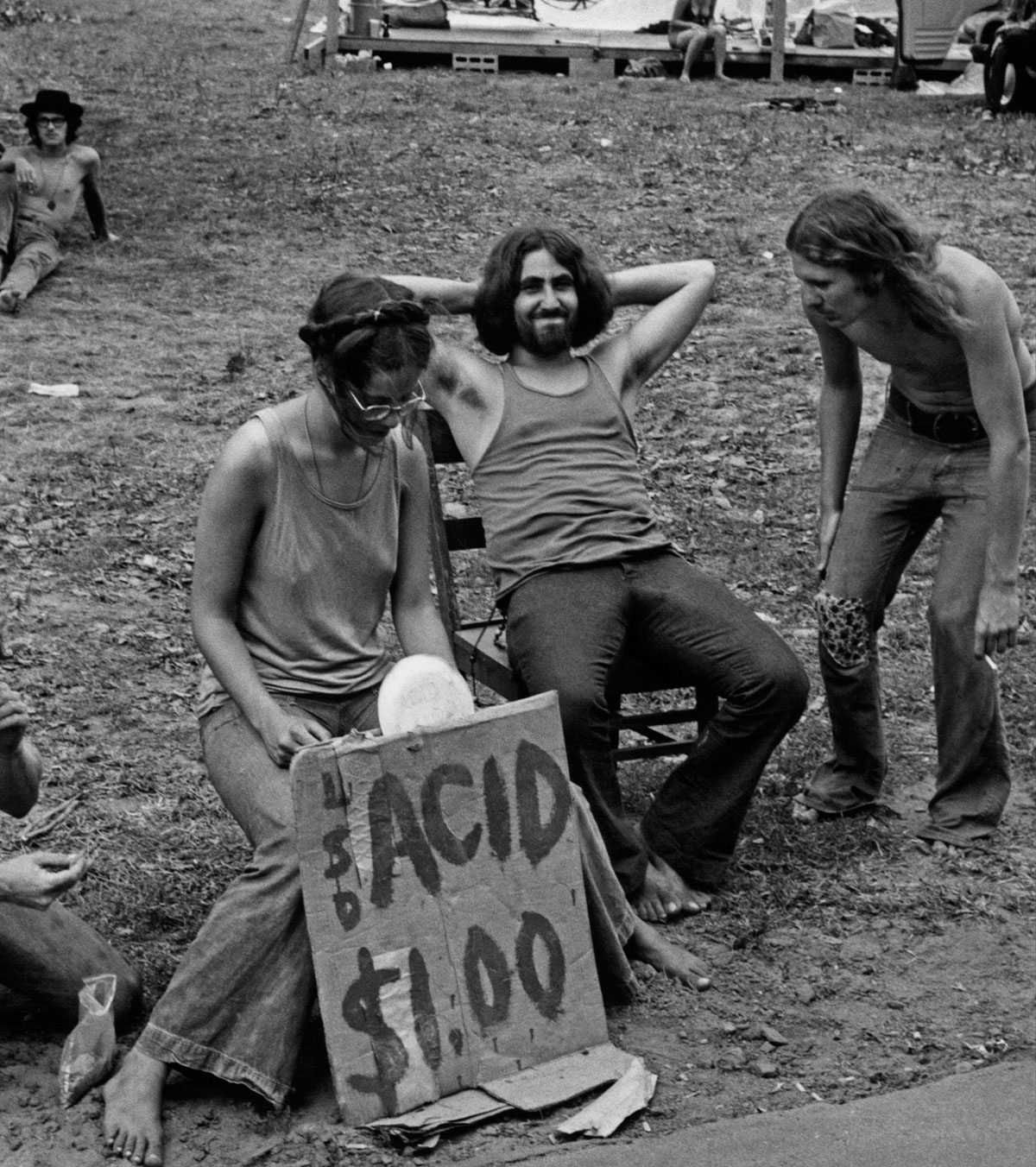

Huyghe has turned the ensuing, abstruse struggles of the Kamitani Lab’s unthinking neural net into an exhibition quite as dramatic as anything he has ever made. Only, this time, the theatrics are taking place almost entirely in our own heads. What are we looking at here? A bottle. No, an elephant, no, a Francis Bacon screaming pig, goose, skyscraper, mixer tap, steam train mole dog bat’s wing…

The closer we look, the more engaged we become, the less we are able to describe what we are seeing. (This is literally true, in fact, since visual recognition works just that little bit faster than linguistic processing.) So, as we watch these digital canvases, we are drawn into dreamlike, timeless lucidity: a state of concentration without conscious effort that sports psychologists like to call “flow”. (How the Serpentine will ever clear the gallery at the end of the day I have no idea: I for one was transfixed.)

UUmwelt, far from being a show about how machines will make artists redundant, turns out to be a machine for teaching the rest of us how to read and truly appreciate the things artists make. It exercises and strengthens that bit of us that looks beyond the normative content of images and tries to make sense of them through the study of volume, colour, light, line, and texture. Students of Mondrian, Duffy and Bacon, in particular, will lap up this show.

Remember those science-fictional devices and medicines that provide hits of concentrated education? Quantum physics in one injection! Civics in a pill! I think Huyghe may have come closer than anyone to making this silly dream a solid and compelling reality. His machines are teaching us how to read pictures, and they’re doing a good job of it, too.