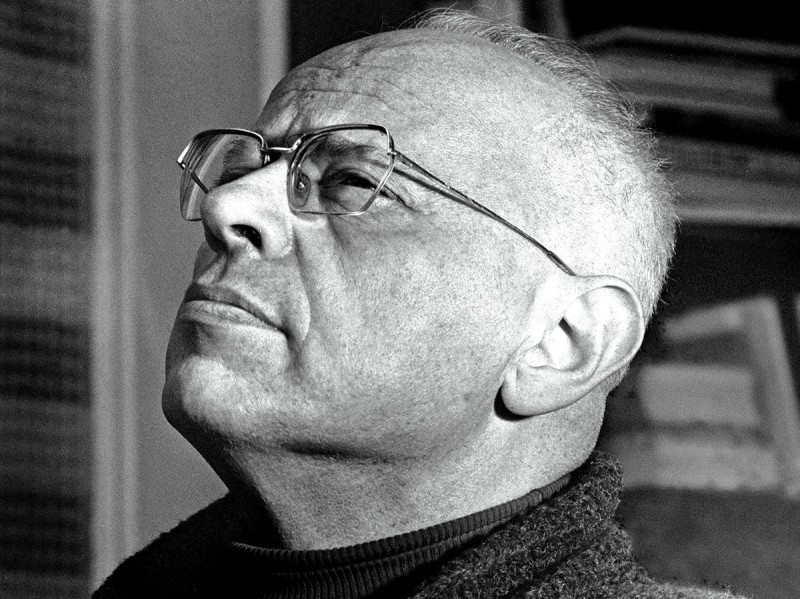

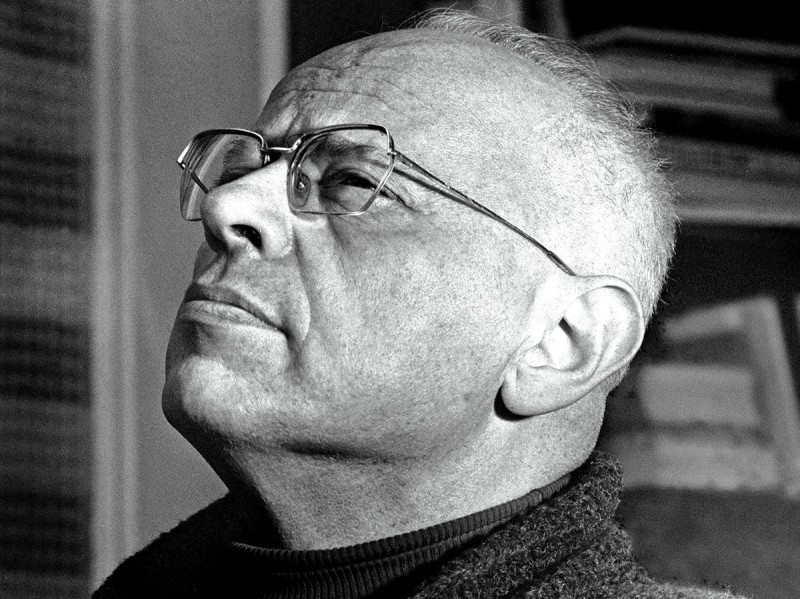

From the 1950s, science fiction writer Stanisław Lem began firing out prescient explorations of our present and far beyond. His vision is proving unparalleled.

For New Scientist, 16 November 2016

“POSTED everywhere on street corners, the idiot irresponsibles twitter supersonic approval, repeating slogans, giggling, dancing…” So it goes in William Burroughs’s novel The Soft Machine (1961). Did he predict social media? If so, he joins a large and mostly deplorable crowd of lucky guessers. Did you know that in Robert Heinlein’s 1948 story Space Cadet, he invented microwave food? Do you care?

There’s more to futurology than guesswork, of course, and not all predictions are facile. Writing in the 1950s, Ray Bradbury predicted earbud headphones and elevator muzak, and foresaw the creeping eeriness of today’s media-saturated shopping mall culture. But even Bradbury’s guesses – almost everyone’s guesses, in fact – tended to exaggerate the contemporary moment. More TV! More suburbia! Videophones and cars with no need of roads. The powerful, topical visions of writers like Frederik Pohl and Arthur C. Clarke are visions of what the world would be like if the 1950s (the 1960s, the 1970s…) went on forever.

And that is why Stanisław Lem, the Polish satirist, essayist, science fiction writer and futurologist, had no time for them. “Meaningful prediction,” he wrote, “does not lie in serving up the present larded with startling improvements or revelations in lieu of the future.” He wanted more: to grasp the human adventure in all its promise, tragedy and grandeur. He devised whole new chapters to the human story, not happy endings.

And, as far as I can tell, Lem got everything – everything – right. Less than a year before Russia and the US played their game of nuclear chicken over Cuba, he nailed the rational madness of cold-war policy in his book Memoirs Found in a Bathtub (1961). And while his contemporaries were churning out dystopias in the Orwellian mould, supposing that information would be tightly controlled in the future, Lem was conjuring with the internet (which did not then exist), and imagining futures in which important facts are carried away on a flood of falsehoods, and our civic freedoms along with them. Twenty years before the term “virtual reality” appeared, Lem was already writing about its likely educational and cultural effects. He also coined a better name for it: “phantomatics”. The books on genetic engineering passing my desk for review this year have, at best, simply reframed ethical questions Lem set out in Summa Technologiae back in 1964 (though, shockingly, the book was not translated into English until 2013). He dreamed up all the usual nanotechnological fantasies, from spider silk space-elevator cables to catastrophic “grey goo”, decades before they entered the public consciousness. He wrote about the technological singularity – the idea that artificial superintelligence would spark runaway technological growth – before Gordon Moore had even had the chance to cook up his “law” about the exponential growth of computing power. Not every prediction was serious. Lem coined the phrase “Theory of Everything”, but only so he could point at it and laugh.

He was born on 12 September 1921 in Lwów, Poland (now Lviv in Ukraine). His abiding concern was the way people use reason as a white stick as they steer blindly through a world dominated by chance and accident. This perspective was acquired early, while he was being pressed up against a wall by the muzzle of a Nazi machine gun – just one of several narrow escapes. “The difference between life and death depended upon… whether one went to visit a friend at 1 o’clock or 20 minutes later,” he recalled.

Though a keen engineer and inventor – in school he dreamed up the differential gear and was disappointed to find it already existed – Lem’s true gift lay in understanding systems. His finest childhood invention was a complete state bureaucracy, with internal passports and an impenetrable central office.

He found the world he had been born into absurd enough to power his first novel (Hospital of the Transfiguration, 1955), and might never have turned to science fiction had he not needed to leap heavily into metaphor to evade the attentions of Stalin’s literary censors. He did not become really productive until 1956, when Poland enjoyed a post-Stalinist thaw, and in the 12 years following he wrote 17 books, among them Solaris (1961), the work for which he is best known by English speakers.

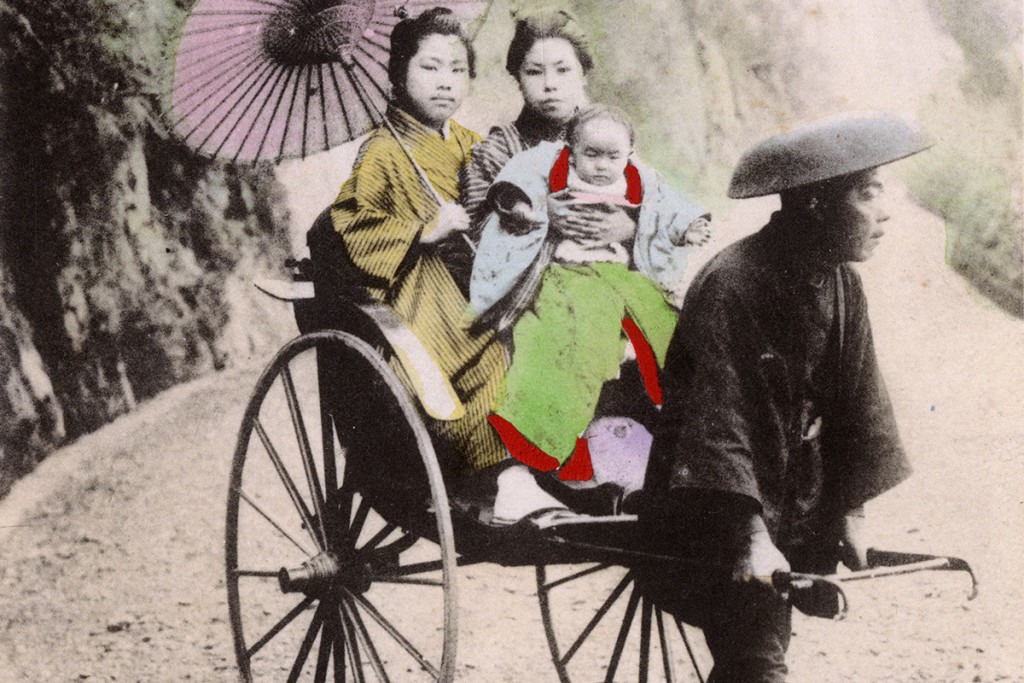

Solaris is the story of a team of distraught experts in orbit around an inscrutable and apparently sentient planet, trying to come to terms with its cruel gift-giving (it insists on “resurrecting” their dead). Solaris reflects Lem’s pessimistic attitude to the search for extraterrestrial intelligence. It’s not that alien intelligences aren’t out there, Lem says, because they almost certainly are. But they won’t be our sort of intelligences. In the struggle for control over their environment they may as easily have chosen to ignore communication as respond to it; they might have decided to live in a fantastical simulation rather than take their chances any longer in the physical realm; they may have solved the problems of their existence to the point at which they can dispense with intelligence entirely; they may be stoned out of their heads. And so on ad infinitum. Because the universe is so much bigger than all of us, no matter how rigorously we test our vaunted gift of reason against it, that reason is still something we made – an artefact, a crutch. As Lem made explicit in one of his last novels, Fiasco (1986), extraterrestrial versions of reason and reasonableness may look very different to our own.

Lem understood the importance of history as no other futurologist ever has. What has been learned cannot be unlearned; certain paths, once taken, cannot be retraced. Working in the chill of the cold war, Lem feared that our violent and genocidal impulses are historically constant, while our technical capacity for destruction will only grow.

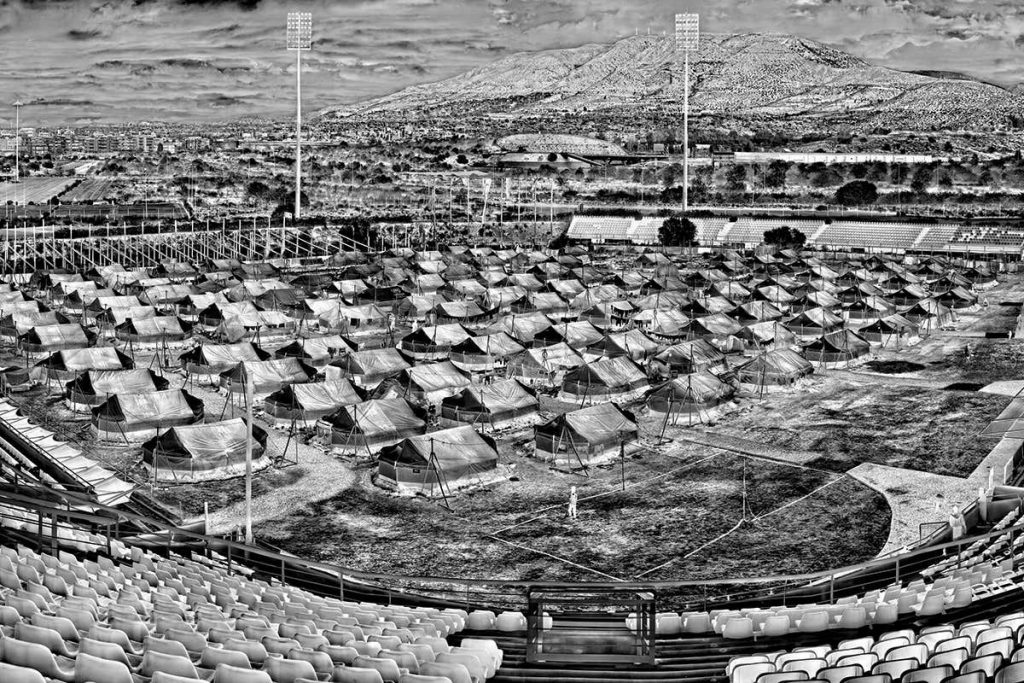

Should we find a way to survive our own urge to destruction, the challenge will be to handle our success. The more complex the social machine, the more prone it will be to malfunction. In his hard-boiled postmodern detective story The Chain of Chance (1975), Lem imagines a very near future that is crossing the brink of complexity, beyond which forms of government begin to look increasingly impotent (and yes, if we’re still counting, it’s here that he makes yet another on-the-money prediction by describing the marriage of instantly accessible media and global terrorism).

Say we make it. Say we become the masters of the universe, able to shape the material world at will: what then? Eventually, our technology will take over completely from slow-moving natural selection, allowing us to re-engineer our planet and our bodies. We will no longer need to borrow from nature, and will no longer feel any need to copy it.

At the extreme limit of his futurological vision, Lem imagines us abandoning the attempt to understand our current reality in favour of building an entirely new one. Yet even then we will live in thrall to the contingencies of history and accident. In Lem’s “review” of the fictitious Professor Dobb’s book Non Serviam, Dobb, the creator, may be forced to destroy the artificial universe he has created – one full of life, beauty and intelligence – because his university can no longer afford the electricity bills. Let’s hope we’re not living in such a simulation.

Most futurologists are secret utopians: they want history to end. They want time to come to a stop; to author a happy ending. Lem was better than that. He wanted to see what was next, and what would come after that, and after that, a thousand, ten thousand years into the future. Having felt its sharp end, he knew that history was real, that the cause of problems is solutions, and that there is no perfect world, neither in our past nor in our future, assuming that we have one.

By the time he died in 2006, this acerbic, difficult, impatient writer who gave no quarter to anyone – least of all his readers – had sold close to 40 million books in more than 40 languages, and earned praise from futurologists such as Alvin Toffler of Future Shock fame, scientists from Carl Sagan to Douglas Hofstadter, and philosophers from Daniel Dennett to Nicholas Rescher.

“Our situation, I would say,” Lem once wrote, “is analogous to that of a savage who, having discovered the catapult, thought that he was already close to space travel.” Be realistic, is what this most fantastical of writers advises us. Be patient. Be as smart as you can possibly be. It’s a big world out there, and you have barely begun.