Last week I received a press release headlined “1 in 4 Brits say ‘No’ to Covid vaccine”. This is was such staggeringly bad news, I decided it couldn’t possibly be true. And sure enough, it wasn’t.

Armed with the techniques taught me by biologist Carl Bergstrom and data scientist Jevin West, I “called bullshit” on this unwelcome news, which after all bore all the hallmarks of clickbait.

For a start, the question on which the poll was based was badly phrased. On closer reading it turns out that 25 per cent would decline if the government “made a Covid-19 vaccine available tomorrow”. Frankly, if it was offered *tomorrow* I’d be a refusenik myself. All things being equal, I prefer my medicines tested first.

But what of the real meat of the claim — that daunting figure of “25 per cent”? It turns out that a sample of 2000 was selected from a sample of 17,000 drawn from the self-selecting community of subscribers to a lottery website. But hush my cynicism: I am assured that the sample of 2000 was “within +/-2% of ONS quotas for Age, Gender, Region, SEG, and 2019 vote, using machine learning”. In other words, some effort has been made to make the sample of 2000 representative of the UK population (but only on five criteria, which is not very impressive. And that whole “+/-2%” business means that up to 40 of the sample weren’t representative of anything).

For this, “machine learning” had to be employed (and, later, “a proprietary machine learning system”)? Well, of course not. Mention of the miracle that is artificial intelligence is almost always a bit of prestidigitation to veil the poor quality of the original data. And anyway, no amount of “machine learning” can massage away the fact that the sample was too thin to serve the sweeping conclusions drawn from it (“Only 1 in 5 Conservative voters (19.77%) would say No” — it says, to two decimal places, yet!) and is anyway drawn from a non-random population.

Exhausted yet? Then you may well find Calling Bullshit essential reading. Even if you feel you can trudge through verbal bullshit easily enough, this book will give you the tools to swim through numerical snake-oil. And this is important, because numbers easily slip past the defences we put up against mere words. Bergstrom and West teach a course at the University of Washington from which this book is largely drawn, and hammer this point home in their first lecture: “Words are human constructs,” they say; “Numbers seem to come directly from nature.”

Shake off your naive belief in the truth or naturalness of the numbers quoted in new stories and advertisements, and you’re half way towards knowing when you’re being played.

Say you diligently applied the lessons in Calling Bullshit, and really came to grips with percentages, causality, selection bias and all the rest. You may well discover that you’re now ignoring everything — every bit of health advice, every over-wrought NASA announcement about life on Mars, every economic forecast, every exit poll. Internet pioneer Jaron Lanier reached this point last year when he came up with Ten Arguments for Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now. More recently the best-selling Swiss pundit Rolf Dobelli has ordered us to Stop Reading the News. Both deplore our current economy of attention, which values online engagement over the provision of actual information (as when, for instance, a review like this one gets headlined “These Two Books About Bad Data Will Break Your Heart”; instead of being told what the piece is about, you’re being sold on the promise of an emotional experience).

Bergstrom and West believe that public education can save us from this torrent of micro-manipulative blither. Their book is a handsome contribution to that effort. We’ve lost Lanier and Dobelli, but maybe the leak can be stopped up. This, essentially, is what the the authors are about; they’re shoring up the Enlightenment ideal of a civic society governed by reason.

Underpinning this ideal is science, and the conviction that the world is assembled on a bedrock of truth fundamentally unassailable truths.

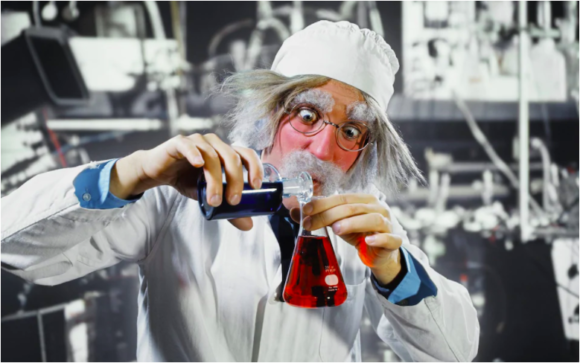

Philosophical nit-picking apart, science undeniably works. But in Science Fictions Stuart Ritchie, a psychologist based at King’s College, shows just how contingent and gimcrack and even shoddy the whole business can get. He has come to praise science, not to bury it; nevertheless, his analyses of science’s current ethical ills — fraud, hype, negligence and so on — are devastating.

The sheer number of problems besetting the scientific endeavour becomes somewhat more manageable once we work out which ills are institutional, which have to do with how scientists communicate, and which are existential problems that are never going away whatever we do.

Our evolved need to express meaning through stories is an existential problem. Without stories, we can do no thinking worth the name, and this means that we are always going to prioritise positive findings over negative ones, and find novelties more charming than rehearsed truths.

Such quirks of the human intellect can be and have been corrected by healthy institutions at least some of the time over the last 400-odd years. But our unruly mental habits run wildly out of control once they are harnessed to a media machine driven by attention. And the blame for this is not always easily apportioned: “The scenario where an innocent researcher is minding their own business when the media suddenly seizes on one of their findings and blows it out of proportion is not at all the norm,” writes Ritchie.

It’s easy enough to mount a defence of science against the tin-foil-hat brigade, but Ritchie is attempting something much more discomforting: he’s defending science against scientists. Fraudulent and negligent individuals fall under the spotlight occasionally, but institutional flaws are Ritchie’s chief target.

Reading Science Fictions, we see field after field fail to replicate results, correct mistakes, identify the best lines of research, or even begin to recognise talent. In Ritchie’s proffered bag of solutions are desperately needed reforms to the way scientific work is published and cited, and some more controversial ideas about how international mega-collaborations may enable science to catch up on itself and check its own findings effectively (or indeed at all, in the dismal case of economic science).

At best, these books together offer a path back to a civic life based on truth and reason. At worst, they point towards one that’s at least a little bit defended against its own bullshit. Time will tell whether such efforts can genuinely turning the ship around, or are simply here to entertain us with a spot of deckchair juggling. But there’s honest toil here, and a lot of smart thinking with it. Reading both, I was given a fleeting, dizzying reminder of what it once felt like to be a free agent in a factual world.