WOLVES BEGAN with an argument. One Christmas, my nephew had a school project to do about grandparents. He asked to copy some wartime photographs of Dad, who’s been dead more than twenty years now. Mum wouldn’t dig any out for him. When I tried to intervene, Mum said my brother must have “got to” me. “I’m not having you two stamping about in my things,” she said. She was in tears.

Well, it’s not much of a step from that to the tale of the Three Little Pigs, is it? A vision of two great rough men huffing and puffing outside the little old lady’s door. And so the title of Wolves – a book that features no such animal – was fixed. What does it mean to discover you’re a wolf? You don’t just wake up one morning and choose to be a predator. It’s a role people hand you sometimes –the dearest, least likely people, often as not. And, whether you want it or not, that’s your mask now. Get used to it.

There were other monkeys on my back at the time. One in particular was John Christopher’s novel The Death of Grass.

For my money, this is the best disaster novel ever written. First published in 1956, it tells the story of a man’s journey from London to a valley hideaway as a virus eradicates all grasses. The science is robust enough but Christopher’s focus, and the book’s lasting value, lie elsewhere: in the sympathetic account of how an ordinary, likeable family man becomes an ordinary, likeable mass-murderer, intruder, kidnapper and procurer of children, fratricide and — finally — King. Because if John doesn’t adapt, disaster will overtake and destroy him, his family, and his followers. “Before all this is over… are we going to hate ourselves?”

I wrote a sort of chatty homage to Christopher for Interzone, some years ago. Wolves is my attempt to do him greater justice – to write a disaster novel for the media-saturated 2010s and say something about why civilisations collapse – almost never through natural disasters; almost always from mounting internal collapse. (Joseph Tainter’s The Collapse of Complex Societies is the other big influence on Wolves, and on much else.)

Wolves began as a memoir and I kept it as close to memoir as I could, even when it began to dawn on me that it might be worth publishing. Everything in Wolves is true apart from the events. How this works is, you wreak a small number of tiny, devastating changes upon your own memories. The nearness of the army base at Sandhurst to where I grew up becomes wounded veterans of Iraq become blind servicemen via the prosthetic vision experiments of Paul Bach y Rita become faceless plastic army men via Toy Story. The skill is in the selection rather than in the free-association itself, just as the secret of a good pizza lies in what you leave out.

What else? I wanted to write something about my brother. But some old and long-lost faces nudged their way in and eventually my two-hander about siblings became a one-hander about a boy’s love of a school friend, and where that leads them both as they grow into adulthood: into power and personal commitments and middle age.

When I was done with it, Mum died, and I went and had a ridiculous affair that destroyed my marriage. I began seeing my brother a lot more, and bought a strange cold flat on a hill and fell in love again. And all the while Wolves – this short, strange tale of personal and globe collapse – was sitting unsold in the back of a drawer, somehow predicting every damned change in my life.

It’s hard for me to remember just how different things were when I wrote the thing, back in 2011 or so. I remember my lovely wife reading and discussing early drafts with me and a shudder rolls down my back.

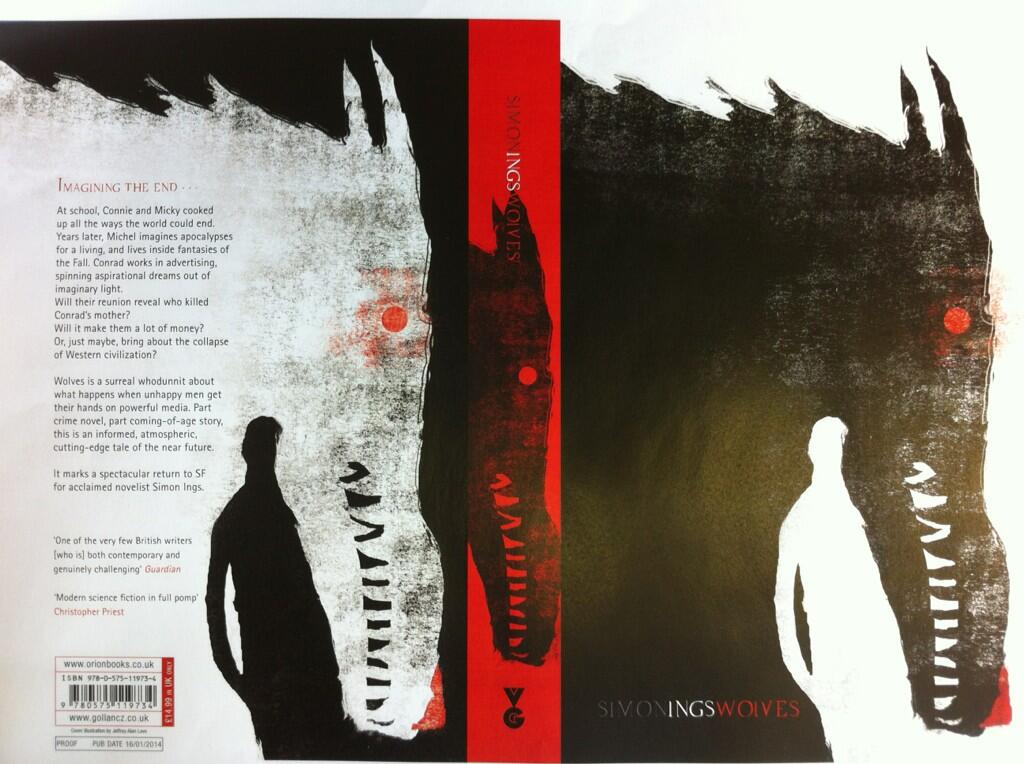

My editor at the time told me Wolves was not publishable. He went so far as to say that publishing it would spoil my reputation (I have one?). When I told my agent this he grinned from ear to ear; I’d handed him exactly the sort of ammunition he needed as he set about moving me to a new house.

All we had to do was sell the idea. And as for that:

Augmented reality – this Google-glassed business of dropping seamlessly contextualised digital artefacts into your visual and auditory frame – is one of a handful of technologies that are likely to transform our lives in the very near future. People talk about the great things AR can show you. Every wall becomes a picture! Every picture becomes a movie! Every object becomes something other, something better than itself – or seems to.

Oddly nobody talks about AR’s ability to hide things. It’s this ability to subtract from the real which interests me the most.

AR has the potential to render the world down to a kind of tedious photographic grammar – the kind employed by commercial image libraries, whose job it is to illustrate stock ideas like ‘busy at work’ or ‘looking after the children’.

This is nothing new. Photography has the ability to do this, obviously. But photography cannot be stuck over (or in) your eyeballs twenty-four hours a day.

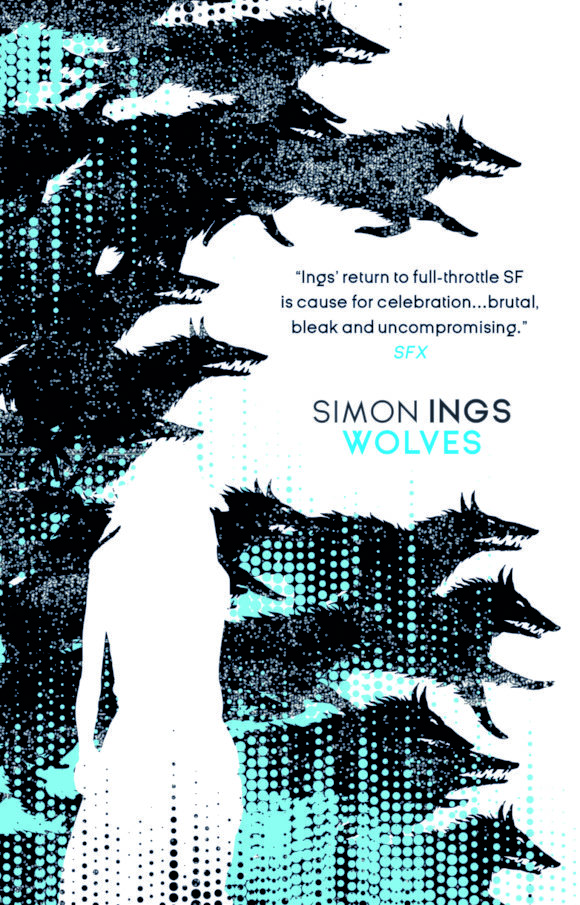

The problems thrown up by AR will not be new. They will be old. They will be fairytale-like problems. The school friends of Wolves create a world that looks modern, looks mediated, looks cool and entertaining and very West Coast. In truth, what they’ve made is a deep, dark wood straight out of the Brothers Grimm. Realising this, they eventually come to see others as sheep, themselves as wolves.

So there you are. That is how we sold the thing. It’s an honest pitch. It tells the truth about the book – though not maybe the deepest truth.

The deepest truth is that for over a year Wolves sat in my drawer, unsellable, malign, predicting, chapter by chapter, the worst year of my life.

So maybe there are wolves in the thing, after all, howling at a CGI moon.

What the reviewers said

Ings has managed to create a convincing present that is, at the same time, as saturated with the comfy patina of the 1970s as Instagram and as prescient as any futurologist – now that Ballard is gone – is likely to get.

Toby Litt, The Guardian

The Guardian, Strange Horizons, Fantasy Book Review, Independent, Flickering Myth, Nerd Like You, Adam Roberts, Rising Shadow, Christopher Priest, the Daily Mail, Nina Allan, Locus, Iain Emseley and Niall Alexander have opinions.