Watching Last and First Men (2020) directed by Jóhann Jóhannsson for New Scientist

“It’s a big ask for people to sit for 70 minutes and look at concrete,” mused the Icelandic composer Jóhann Jóhannsson, about his first and only feature-length film. He was still working on Last and First Men at the time of his death, aged 48, in February 2018.

Admired in the concert hall for his subtle, keening orchestral pieces, Jóhann Jóhannsson was well known for his film work: Prisoners (2013) and Sicario (2015) are made strange by his sometimes terrifying, thumping soundtracks. Arrival (2016) — about the visitation of aliens whose experience of time proves radically different to our own — inspired a yearning, melancholy score that is, in retrospect, a kind of blockbuster-friendly version of Last and First Men. (It’s worth noting that all three films were directed by Denis Villeneuve, himself no stranger to the aesthetics of concrete — witness 2017’s Blade Runner 2049.)

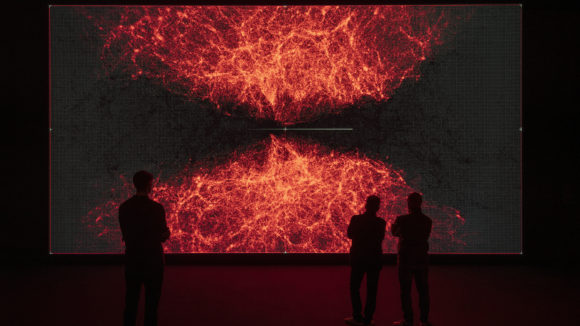

Jóhannsson’s Last and First Men is, by contrast, contemplative and surreal. It’s no blockbuster. A series of zooms and tracking shots against eerie architectural forms, mesmerisingly shot in monochrome 16mm by Norwegian cinematographer Sturla Brandth Grøvlen, it draws its inspiration and its script (a haunting, melancholy, sometimes chilly off-screen monologue performed by Tilda Swinton) from the 1930 novel by British philosopher William Olaf Stapledon.

Stapledon’s day job — lecturing on politics and ethics at the University of Liverpool — seems now of little moment, but his science fiction novels have never been out of print, and continue to set a dauntingly high bar for successors. Last and First Men is a history of the solar system across two billion years, detailing the dreams and aspirations, achievements and failings of 17 different kinds of future Homo (not including sapiens).

In the light of our ageing sun, these creatures evolve, blossom, speciate, and die, and it’s in the final chapters, and the melancholy moment of humanity’s ultimate extinction, that Jóhannsson’s film is set. Last and First Men is not a drama. There are no actors. There is no action. Mind you, it’s hard to see how any attempt to film Stapledon’s future history could work otherwise. It’s not really a novel; more a haunting academic paper from the beyond.

The idea to use passages from the book came quite late in Jóhannsson project, which began life as a film essay on (and this is where the concrete comes in) the huge, brutalist war memorials, called Spomenik, erected in the former Republic of Yugoslavia between the 1960s and the 1980s.

“Spomeniks were commissioned by Marshal Tito, the dictator and creator of Yugoslavia,” Jóhannsson explained in 2017 when the film, accompanied by a live rendition of an early score, was screened at the Manchester International Festival. “Tito constructed this artificial state, a Utopian experiment uniting the Slavic nations, with so many differences of religion. The spomeniks were intended as symbols of unification. The architects couldn’t use religious iconography, so instead, they looked to prehistoric, Mayan and Sumerian art. That’s why they look so alien and otherworldly.”

Swinton’s cool, regretful, monologue proves an ideal foil for the film’s architectural explorations, lifting what would otherwise be a stunning but slight art piece into dizzying, speculative territory: the last living human, contemplating the leavings of two billion years of human history.

The film was left unfinished at Jóhannsson’s death; it took his friend, the Berlin-based composer and sound artist Yair Elazar Glotman, about a year to realise Jóhannsson’s scattered and chaotic notes. No-one, hearing the story of how Last and First Men was put together, would imagine it would ever amount to anything more than a tribute piece to the composer.

Sometimes, though, the gods are kind. This is a hugely successful science fiction film, wholly deserving of a place beside Tarkovsky’s Solaris and Kubrick’s 2001. Who knew that staring at concrete, and listening to the end of humanity, could wet the watcher’s eye, and break their heart?

It is a terrible shame that Jóhannsson’s did not live to see his hope fulfilled; that, in his own words, “we’ve taken all these elements and made something beautiful and poignant. Something like a requiem.”