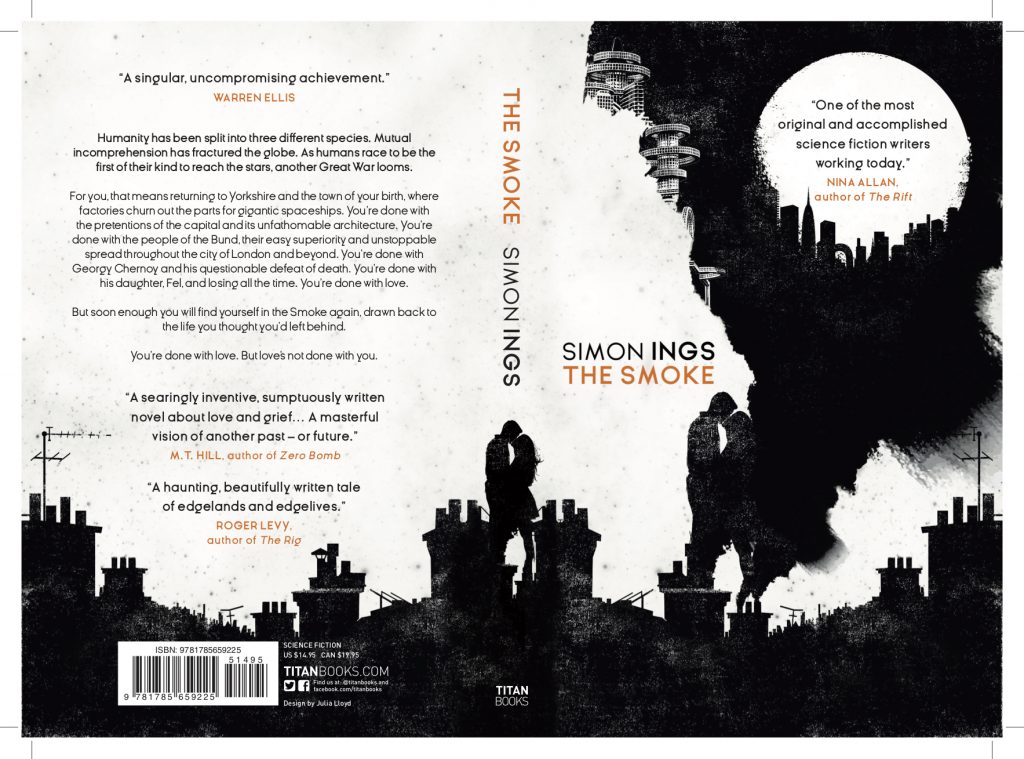

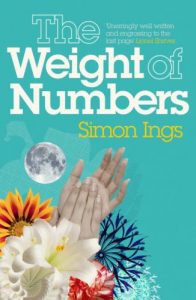

On July 21, 1969 two astronauts set foot on the moon; far below, in ravaged Mozambique, a young revolutionary is murdered by a package bomb.

Strung like webs between these two unconnected events are three lives: Anthony Burden, a mathematical genius destroyed by the beauty of numbers; Saul Cogan, transformed from prankster idealist to trafficker in the poor and dispossessed; and Stacey Chavez, ex-teenage celebrity and mediocre performance artist, hungry for fame and starved of love. All are haunted by Nick Jinks, a man who sows disaster wherever he goes. As a grid of connections emerges between a dusty philosophical society in London and an African revolution, between international container shipping and celebrity-hosted exposés on the problems of the Third World, The Weight of Numbers sends the spectres of the baby boom’s liberal revolutions floating into the unreal estate of globalization and media overload

What the reviewers said

Having cut his teeth on a series of intelligent thrillers, Ings makes a bid for the literary big time with this stunning, gutsy novel that takes a single incident—the suffocation of 58 immigrants in a lorry bound for Scotland—and traces back its causes through the life stories of those involved. Dozens of deftly drawn characters, an acute understanding of geopolitics, an epic historical sweep and a serious talent for storytelling make this one of the most exciting—and relevant—books of the last year. Booker material, for sure.

Arena

In the corner of the literary landscape in which a few of us sit, hunting for ways to work ever exciting and dynamic thinking from the sciences into the contemporary novel, The Weight of Numbers is extremely good news. It’s a dynamic, innovative, and compelling book that brings into focus some of the most interesting trends in contemporary fiction, and Simon Ings deserves more than a sniff of at least one prize for his efforts.

James Flint, The Daily Telegraph

It is unlikely there will be a finer written fiction this year. . . . Ings stalks his targets with the relentlessness of a bounty hunter, until he arrives at a new heart of darkness with the important discoveries that in the vacuum of contemporary life there is nothing to distinguish the apparently morally dubious world of human trafficking from the ‘migrainous white noise of the subsidised arts,’ and that self-expression is no more guarantee of satisfaction than silence.

Chris Pettit, The Guardian

[An] ambitious, exciting novel . . . Ings’s prose can ascend into theoretical, visionary territory, but is rooted in the mess of human experience. A sudden sexual encounter in a bombed-out London library, an anorexic slicing a muffin in a Florida restaurant, a horror show of violence in Mozambique — these are unforgettable scenes, evoked with a lean, immediate physicality.

Tom Gatti, The Times

Its stupendous breadth leaves you giddy.

Nottingham Evening Post

The scale of Ings’s ambition is proportionally matched by the precision of his prose. Every sentence, image and line of dialogue is balanced and true. It isn’t its clever design or technical achievement that makes it compelling so much as its beating human heart.

The Independent on Sunday (UK) (5/5 Stars)

This novel could have collapsed under the scale of its own ambition. But instead it triumphs.

Sunday Business Post

Ings weaves an ingenious, shimmering web of contiguity and chance. . . . A feat of meticulous plotting . . . Ings’s project is not dissimilar from David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas, with which it has been compared.

Alistair Sooke, The New Statesman

Characters emerge from different places, periods and experiences, and yet their fraying threads are teasingly revealed to be of the same fabric….Ings has wrought an unorthodox anti-history of the past six decades. The Weight of Numbers is a dizzying feat, redolent of Don DeLillo and David Mitchell in its density. Only when its framework is revealed are its mysteries unraveled.

Gavin Bertram, New Zealand Listener

Simon Ings’ ambitiously genre-defying The Weight of Numbers is a virtuoso display of imaginative plotting.

Financial Times, ‘Novels of 2006’

A Scheherazade of a novel, executed with scope, daring, and humour. The Weight of Numbers is unerringly well written, and engrossing to the last page.

Lionel Shriver, author of We Need to Talk About Kevin

Like Don DeLillo’s Underworld, Simon Ings’s remarkable new work delivers nothing less than a secret key, a counterhistory, of the last sixty years. Ings’s fiction is vivid and swift, a thing of scenes and people, smugglers and astronauts, spies and revolutionaries. But beyond the topical excitements lies something even grander—a vision of our culture as a death ship. The Weight of Numbers is amazing.

Mark Costello, author of Big If