“It’s like a cheetah going after a wildebeest,” says Judith Armitage, lead scientist for Bacterial World, an exhibition at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History. She’s struggling to find a simile adequate to describe Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus, a predatory bacterium found, among other places, in the human gut. Indeed, it’s monstrously fast: capable of swimming 100 times its own body length every second.

Other bacteria are built for strength, not speed. Campylobacter jejuni, which we have to thank for most of our food poisoning, has a propeller-like flagellum geared so that it can heave its way through the thick mucus in the gut.

Armitage has put considerable effort into building a tiny exhibition that gives bacteria their due as the foundational components of living systems –and all I can think about is food poisoning. “Well that’s quorum sensing, isn’t it?” says Armitage, playing along. “After 24 hours or so biding their time, they decide there’s enough of them they can make you throw up.”

Above our heads hangs artist Luke Jerram’s gigantic inflatable E. coli, seen floating over visitors at the first New Scientist Live festival in 2016. It seems an altogether more sinister presence in Oxford’s Museum of Natural History: the alien overseer of a building so exuberantly Gothic (built in 1860, just in time for the famous evolution debate between Thomas Huxley and “Soapy Sam” Wilberforce, the Bishop of Oxford) that it appears more grown than made.

Armed with just 55 exhibits, from the Wellcome Collection, the Pitt Rivers Museum and the Natural History Museum in London, Armitage has managed to squeeze 3.8 billion years of history along a narrow balcony just under the museum’s glass roof. Our journey is two-fold: from the very big to the very small, and from the beginnings of life on Earth to its likely future.

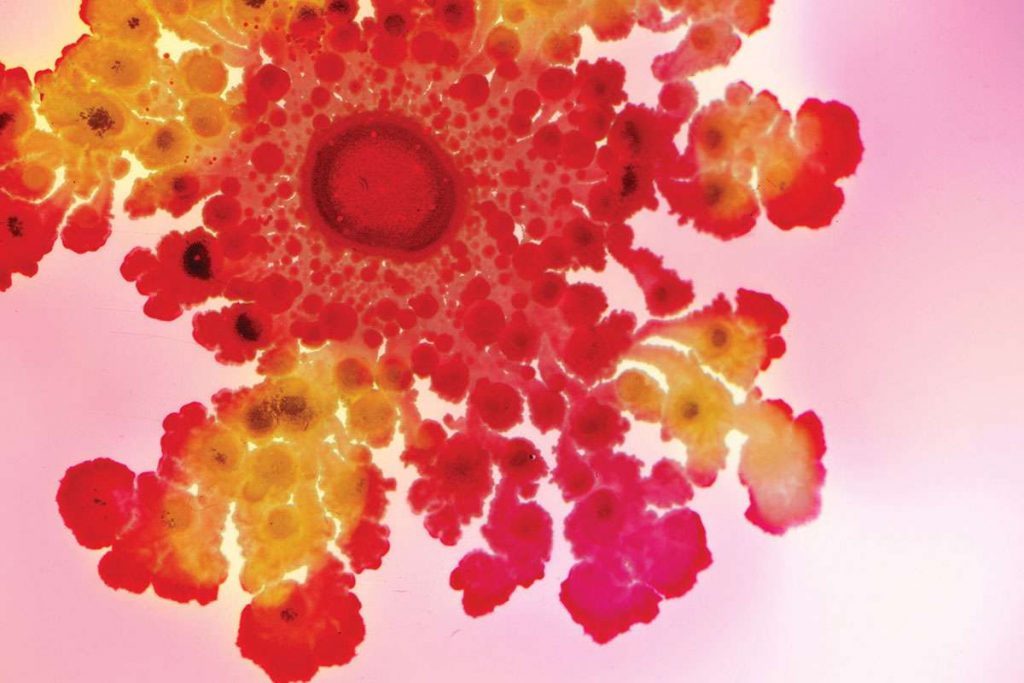

Towering stromatolites, the earliest fossil evidence of life on Earth, reveal the action of countless anaerobic bacteria whose trick of splitting water would result, a million years later, in an extremely rusty planet filling up with toxic oxygen. To survive, let alone thrive, in the ghastly conditions ushered in by the Great Oxygenation Event required bacterial adaptations on which all living things today depend. For example, Paenibacilla (pictured) promote crop growth, and symbiotic bacteria of the genus Rhizobium pack essential hard-to-get at iron into our vegetables. Cellular adaptations defend against caustic oxygen, and have, incidentally, thrown up all manner of unforeseen by-products, including the bioluminescence of certain fish.

As multicellular organisms, we owe the very structure of our cells to an act of bacterial symbiosis. Our biosphere is shaped to meet the needs of ubiquitous bacteria like Wolbachia, without which some species of environmentally essential insect cannot reproduce, or even survive.

Naturally, we humans have tried to muscle in on this story. For a while we’ve been able to harness some bacteria to fight off others, thereby ridding ourselves of disease. But Armitage fears the antibiotic era was just a blip. “New antimicrobials are too expensive to develop,” she observes. “Once they’re shown to work they’ll be kept on the shelf waiting for the microbial apocalypse.”

But look on the bright side. At least once the great Throwing Up is over and the human population shrinks to a disease-racked minimum, the bacteria released from our ballooning guts can get back to what they’re good at: creating vibrant ecosystems out of random raw material. “Bacteria will eat all the plastic.” Of this Armitage is certain. “But,” she adds, “it takes time for metabolic cascades to evolve. We’ll probably not be around to see it happen.”

On the way out, my eye is caught by another artwork: uneasy and delicate pieces of crochet by Elin Thomas depicting colonies of bacteria. The original colonies were grown on personal objects: a key, a gold wedding ring; a wooden pencil. A worn sock.

Microbial World is a tremendous exhibition, punching way above its tiny weight. It doesn’t half put you in your place, though.