Exploring London’s hidden rivers for the Financial Times, 8 June 2019

Early in the eleventh century, King Cnut sailed his troops from the Thames all the way up the river Effra to Brixton. But by the time Victoria took the throne, a millennium later, the Effra had vanished: polluted; canalised; in the end, buried.

The story goes that once during Victoria’s reign, a coffin from West Norwood Cemetery was found bobbing out to sea along the Thames. The Effra had undermined the burial plot from below, then carried the coffin four miles to its outflow, under what is now the MI6 building in Vauxhall.

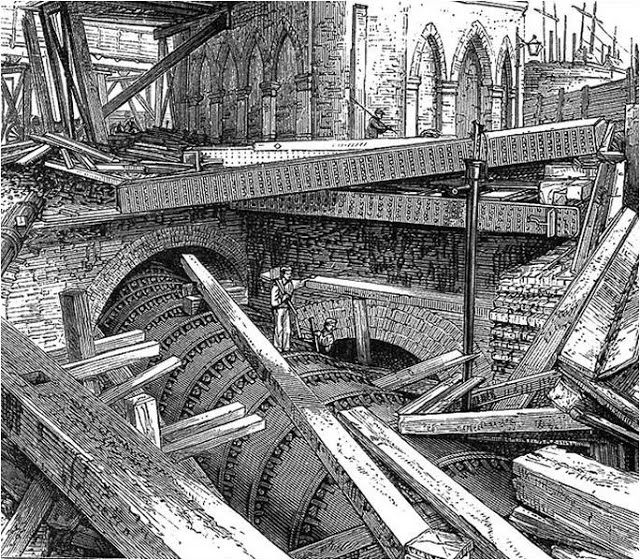

It’s stories of this sort which make Londoners grateful for Joseph Bazalgette, the civil engineer who got London’s rivers working again. Following the Great Stink of 1858, he was given the job of turning them into closed sewers. By integrating the Thames’s tributaries into his underground system, Bazalgette sealed the capital’s noisome waterways from view, and used them to move London’s effluent ever eastwards and away.

The problem Bazalgette solved was an old one. London’s Roman founders also had trouble with its rivers. They’d first camped along the banks of the Walbrook, between the two low lying hills of Ludgate and Cornhill. “At first the river was full and reasonably fast-flowing,” explains Kate Sumnall, archaeologist and co-curator of the Secret Rivers exhibition at the Museum of London Docklands. “Twenty years later, the character of the river had completely changed.” River levels dropped dramatically while, at the same time, floods became more frequent. The Romans tried to manage the river by raising ground levels, building revetments, and straightening its course, all with the idea of getting flood waters away as fast as possible. It’s an approach urban planners copied, with refinements, well into the 1960s, and all over London the consequences run, unseen, below people’s feet

I’ve met Sumnall and her co-curator Thomas Ardill at a cafe in Smithfield Market, not far from the banks of the noisome Fleet river — a stretch of waterway no one in their right mind would ever want to uncover; a ditch that inspired Ben Jonson’s coprophilic masterwork “On the Famous Voyage”, once dubbed the filthiest and most deliberately and insistently disgusting poem in the English language.

After the Great Fire, Christopher Wren wanted to turn the Fleet into a sort of Venetian canal: the sheer number of dead dogs floating in the ooze defeated his plans. It’s has since been given a decent burial under Farringdon Road.

In the company of Sumnall and Ardill, the vanished Fleet Ditch comes to life beneath our feet. Every side street was once a wharf. Coal was piled up in Newcastle Close. Dig under Stonecutter Street and you come up with whetstones and knives. Every hump in Farringdon Road marks an old bridge.

Could things have turned out differently for London’s lost rivers? Probably not, but it’s fun to tinker. Ardill tells me about a group of artist-activists called Platform. In 1992 they set up a mock Effra Redevelopment Agency to consult the residents of Brixton about their plans to open up the local river. A sylvan wonderland awaited those who didn’t mind losing their houses.

Compare this mischievous exercise in grass-roots democracy with the paralegal shenanigans of the Tyburn Angling Society, which explores the legal aspects of restoring the river so that it flows freely through the more exclusive enclaves of west London. Levies charged on newly river-fronted properties will pay for the compulsory purchase orders. Buckingham Palace is one of the buildings the Society has earmarked for demolition.

Real-world efforts to restore stretches of London’s rivers began in 2009. Of London’s nearly 400 miles of river network, just twenty have been restored, but developers and councils are beginning to appreciate the cachet a river can add to an area, plus the improvements it can bring by way of social cohesion and well-being. Sixty more miles of waterway run through the city’s public parks and existing urban regeneration schemes, and can be restored at relatively low cost.

Dave Webb, the ecologist who chairs the London River Restoration Group, began his working life trying to ameliorate the effects of engineering projects that canalised and culverted “unsightly” and “dangerous” watercourses. Now he’s bringing these formerly dead rivers back to light and life.

One difficulty for advocates like Webb is in conveying what restoration actually entails. “Architects have a habit of dreaming up a lovely wildlife space, only to insist that it mustn’t then change. Restoring a river is not like restoring a table. You’re reawakening a natural process. You’re enabling the river to adjust and move around.”

Webb has been energetically promoting London Rivers Week, a festival to promote London’s stretches of restored river. The point is not just to prettify the city. It’s to make London sustainable as the climate changes. If the capital leaves its waterways running underground in concrete channels much longer, flash flooding will start to erode its infrastructure. Toxins concentrated on road surfaces during droughts will enter the water system after a single downpour, poisoning everything downstream. Not that much would survive a drought anyway, since smooth concrete surfaces do not provide plants and animals with sanctuary in dry weather, the way a river’s pools and puddles will.

Webb shows me an alternative to London’s existing bleak, brutalist riverine architecture: the restoration of the Quaggy River in Sutcliffe Park, in the Royal Borough of Greenwich. The park works as a giant sponge, against the day a flood-swollen Quaggy threatens to inundate the neighbouring borough of Lewisham. In normal weather the Quaggy also overflows, less spectacularly, to feed a small wetland which you can enter along a boardwalk. There are dragonflies and mayflies. There are fish, and kingfishers to eat the fish. Above all there are people — twice as many as there used to be when the park was flat and dry. Plus they spend double of the amount of time here that they used to.

“I remember walking along one London river when it was still a concrete channel,” Webb recalls. “I asked what all the iron railings were for and I was told it was to stop kids falling into the water, which was about five inches deep. ‘Well,’ I was told, ‘there’s also the business of them throwing shopping trolleys in it.’ I’ve found that if you give people a river, they won’t spoil it.”

And sure enough, in this not very affluent and fairly unprepossessing stretch of south London, the river shimmers under the dappled shade of self-seeded willow trees. Webb reckons there was nothing particularly heroic about the engineering involved: “In a lot of cases, there’s not even any need for planting. The ecologies of the river’s headwaters will work their way downstream in the course of a few seasons, and birds and insects follow very quickly.”

Webb also recommends a walk along the Wandle, which passes through Croydon, Sutton, Merton, and Wandsworth to join the River Thames. This chalk stream was once the heaviest-worked river in the capital, driving mills to produce everything from paper to gunpowder, snuff to textiles. Declared dead in the 1960s, now it’s a breeding spot for chub and dace and brown trout. From certain angles, it will fool you into thinking you’ve hit a particularly idyllic nook of the South Downs. Turning a corner will quickly remind you of the city’s presence, but that’s the peculiar, liminal charm of an urban river.

While Thames 21, the charity behind London Rivers Week, organises citizen science projects, clean-ups and campaigns, the Museum of London Docklands’ Secret Rivers exhibition has scheduled a series of guided walks to enjoy over the summer. On 8 June you can follow the track of the the Walbrook, the river that made Londinium possible. In July you can sneak off from the line of the Tyburn to go shopping in Bond Street, or follow the gruesome Neckinger, the foul, lead-poisoned stream in which Bill Sykes got his just desserts in Dickens’s Oliver Twist. And I’m particularly looking forward to mid-August, when stretches of the Wandle will dazzle in the sun.