Visiting Nam June Paik at Tate Modern for the Financial Times, 24 October 2019

In 1963 one of the more notorious members of Darmstadt’s new music community, Nam June Paik, stuck around fifty strips of audio tape to the wall of the Galerie Parnass in Wuppertal in Germany.

“I wanted to let the audience… act and play by itself,” he wrote, “so I have resigned the performance of music… I made various kinds of musical instruments… to expose them in a room so that the congregation may play them as they please.”

Exhausted and alienated by the difficult musics coming out of Darmstadt — Pierre Boulez, Karlheinz Stockhausen, serialism and all the rest — visitors lapped up Paik’s free-wheeling alternative. You’d go up to the wall and rub the playback head of a dismantled tape recorder along the strips, back and forth, hunting for sounds, scratches, white noise, and hey presto! you almost became a composer.

“You have to be a lot rougher with this than you think,” a gallery worker explained, showing me the Tate’s recreated Random Access. “Really scrape.”

So I scraped. And I still couldn’t get much of a sound out of the wall-mounted speakers, and now the gallery wall is covered in dirty brown ferrous oxide streaks.

The original wasn’t very effective, either. The point was that Paik was giving you permission to play, to experiment. The Swiss artist and career eccentric Josef Beuys took Paik at his word and destroyed one of the the pianos in Paik’s first solo show with an axe. And Paik dug it; they became lifelong friends.

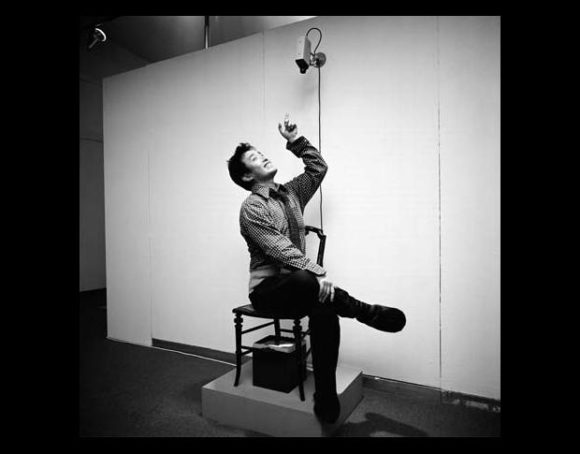

How do you represent an artist whose chosen medium is the audience? Who spends his time chivvying it into life by gestures, situations, shocks, pornography? How do you preserve Zen of Head (1962), in which Paik dipped his head in black ink and used it to draw a line on a length of paper? How do you honour his nearly thirty-year collaboration with the cellist and performance artist Charlotte Moorman, when Variations on a Theme by Saint-Saens (1969) involves her climbing up a ladder and vanishing into a water-filled oil drum?

The many representative works gathered by the Tate can only go so far to represent Paik’s whole practice. TV Buddha (1974) is a statuette of a seated Buddha, gazing at its own televised image. Three Eggs (1975-82) — one real, one nested in an empty television, and the third a televised image of the first egg — goes beyond mere solipsism to suggest something more complex. There are robots made from TV sets here, lines of code from early experiments at Bell Labs in New Jersey, abd TV bras and TV spectacles that seem to have fallen out of one of the calmer moments of the Japanese cyberpunk horror flick Tetsuo: The Iron Man. Newcomers would be left hopelessly at sea were it not that the Tate has also assembled a huge amount of documentation, and arranged it in a fashion that is not just informative: it’s revelatory.

Programmes. Posters. Photographs. Snatches of 8mm. Mostly they record events in tiny rooms, the visitors all crammed together, everyone laughing, having a good time. Wall by wall, case by case, we begin to understand what we missed.

Paik was a collector, a collaborator, an impresario. He urged others to enact the strangest dreams. In New York, in 1964, a topless Charlotte Moorman saws away at her cello, and Alison Knowles sheds her panties and shoves them down the throat of the least talented art critic in the room.

But Paik had other dreams, too, which which for years he kept strictly to himself. As early as 1961 he had given up studying art and was avidly reading Popular Mechanics. In Tokyo, with the engineer Shuya Abe, he co-invented the Paik-Abe Video Synthesizer. This added single-colour channels to broadcast images in real time, distorted, colorised, and superimposed multiple images, and was in essence the technology that would soon give Top of the Pops and the MTV music channel their visual signature.

Paik’s use of TV as a medium is now what everyone most remembers about him, thanks mostly to his monumental “matrices”: sculptural video collages assembled using steel gantries and neon tubing and multiple cathode-ray televisions. There’s a late example here called Internet Dream (1994), and nearby, a recreation of the video installation Sistine Chapel, which in 1993 graced the pavilion of a newly-unified Germany at the Venice Biennale. Thrown across walls and ceiling by TV projectors, disembodied David Bowies and Janis Joplins, Lou Reeds and Ryuichi Sakamotos jostle for space with parties of Gobi desert Mongolians. It’s intoxicating. Dated. Kitsch. It’s the fruit both in flower and in rot.

“Thanks to Paik,” he wrote about himself (never a good sign) ” we discover that our entire world can become sound — or rather that it *is* sound… he does away with structure once and for all.”

And, oh dear, just look where that liquefaction has led. By giving us permission to create, Paik stripped away the structures that let us receive, appreciate, and judge. His mentor John Cage did much the same for music. And around Cage and Paik, Moorman and Beuys swirled a loose, revolutionary band of brothers and sisters who, under the banner of a movement called Fluxus, abandoned the commodified single art object and sought to create democratic art; an art of the everyday.

The idea that audiences also knew something about art filled these self-appointed shamans with impatience. The audience’s ideas were third-hand, third-rate, bourgeois prisons from which they might yet be liberated.

Liberated into what, though? Into boredom? Into consumption? All you can do with this work is participate in it. Swallow it. Go see In Real Life, Olafur Eliasson’s collection of kid-friendly novelties, if you want to see where this attitude leads. It runs next door till January 5.

As I left Paik’s show, I paused by a wall-mounted TV, where pianist Manon-Liu Winter plays her own composition on Paik’s prepared piano (now too fragile to travel). The one with the barbed wire, whose keyboard once triggered sirens, heaters, ventilators and tape recorders.

Now, though, it’s just a ruined piano. Winter picks her way across its atrocious keyboard like Jack Skellington, trying to discover the secret of Christmas by measuring the presents under the tree with a tape measure. This is indeed a revelatory exhibition — but you may come away liking Paik less.