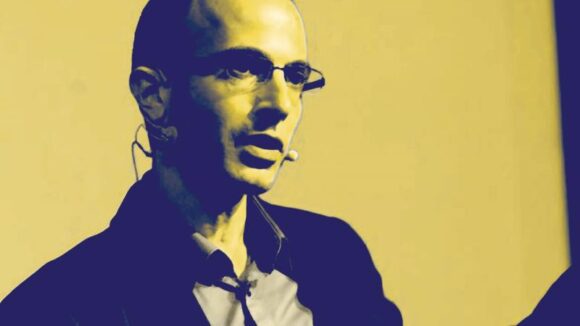

“And just think how sad the last mammoth must have been all on her own,” writes Yuval Noah Harari, as he invites his pre-teen audience to contemplate our species’ long track record in wiping out countless varieties of big animal (giant flightless birds; elephantine sloths; the list is long).

Harari is spreading his young person’s history of humankind across four illustrated volumes. This is the first, and describes how we managed to exterminate our way to planetary dominance (so a certain mawkishness is allowable). Following the Bauplan of Harari’s 2011 adult bestseller Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, we can reasonably look forward to a triumphalist futuristic fourth volume in which all the monsters that terrified and/or fed our ancestors are resurrected by our CRISPR-wielding post-human descendants and released into some sort of 3D-printed world zoo.

Why survey such a vast sweep of evolutionary history through the keyhole of “what we really know”? Why not say what you’ve got to say, and leave the error-correction to your young reader’s own curiosity and further reading? When I was a kid, Patrick Moore was still writing about Venus’s already rather unlikely world ocean. I was inspired by such unchained speculation, and I don’t think I sustained any lasting intellectual harm.

But we are where we are: the world is haunted by the spectre of untruth and is besotted with the wisdom of crowds, and Harari is at pains in his afterword to point out how carefully staff at Penguin and his own “social impact company” Sapienship weighed every sentence and every illustration, lest it might misrepresent something or “hurt people”.

As a consequence, How Humans Took Over the World is, for all its many strengths, one of the least odd books I have ever read.

How Humans Took Over the World is an easy-to-read epic that sets out to be scrupulously truthful about what we do and do not know about the past. In simple, direct terms, Harari explains that we’re the only species that believes stories; stories enabled cooperation; and cooperation made it possible for us to smother and consume large amounts of the planet.

Harari’s ebullience as a storyteller is infectious. No sooner does he dry his eyes over the fate of the mammoth, than he is gleefully explaining how easy they were to get rid of. (With that long a gestation period, and that small a herd, you only had to kill a couple of mammoths a year to wipe them out.)

Harari’s concludes that we’re not a very nice species. This is risky, if only because self-hate is cheap and saves us the trouble of doing anything or changing anything about ourselves. The gloomy shade of Jean-Jacques Rousseau hovers over Harari’s dismissal of religion as a means by which powerful hominins cozened an unfair quantity of bananas from their weaker brethren. The idea that religion might be humanity’s millennia-old effort to tell uplifting stories about itself, all in the teeth of cosmic meaninglessness and the inevitability of death, gets no look-in here, though Harari still spends an inordinate amount of time being kind to the blarney and tosh spun by animists and shamans, those snake-oil salesmen of yore.

Harari’s setting us up for a thunderous and inspiring last chapter, in which we see Homo sapiens poised to use its storytelling superpower to more constructive effect.

If thousands of people believe in the same story, then they’ll all follow the same rules, and this is why we rule the world (“whereas poor chimps are locked up in zoos”).

To save the world we have been so busy consuming, we need to come up with a story about ourselves that’s better than the ones we’ve told each other in the past (or, to be less judgemental about it, a story that’s better suited to our planet’s present).

“If you can invent a good story that enough people believe,” Harari writes, “you can conquer the world.”

It is unlikely that this will be written by Harari. Though he’s packaged as a seer, there’s little in his work that is truly surprising or sui generis.

His chief skill — displayed here even more remarkably than in his work for adults — is his ability to spin complex material into a rollicking tale while still telling the truth.