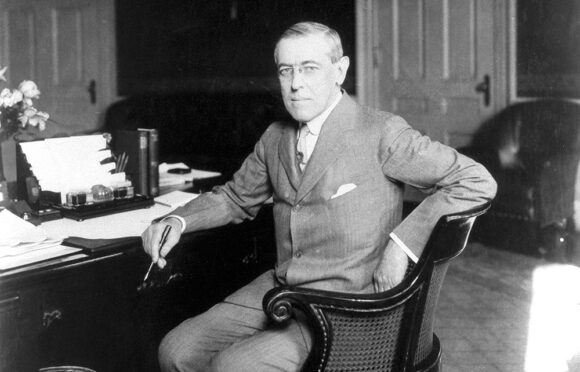

It was a vision US president Woodrow Wilson could not resist, and it was instrumental in bringing the US into the Great War.

The treaty at Versailles and the League of Nations founded during the negotiations were meant, not just to end the current war, but to end all future wars, by ensuring that a country taking up arms against one signatory would be treated as a belligerent by all the others.

Wilson took his advisor Edward “Colonel” House’s vision of a new world order and careered off with it.

Against advice, he attended Versailles in person, let none of his staff in with him during negotiations, was quickly overwhelmed, saw his principled “fourteen points” deluged by special provisions and horse-trading, and returned home, convinced, first, that his dearest close colleagues had betrayed him (which they hadn’t); second, that the League of Nations alone could mend what the Treaty of Versailles had left broken or made worse (which it didn’t); third, that that he was the vessel of divine will, and that what the world needed from him at this crucial hour was a show of principle and Christ-like sacrifice. “The stage is set,” he declared to a dumbfounded and sceptical Senate, “the destiny is disclosed. It has come about by no plan of our conceiving, but by the hand of God who has led us into this way. We cannot turn back.”

Winston Churchill had Wilson’s number: “Peace and Goodwill among all Nations abroad, but no truck with the Republican party at home. That was his ticket and that was his ruin and the ruin of much else as well.”

When it was clear he would not get everything he wanted, Wilson destroyed the bill utterly, needlessly ending US involvement in the League before it had even begun.

Several developments followed ineluctably from this. Another world war, of course; also a small but vibrant cottage industry in books explaining just what in hell Wilson had thought he was playing at. Patrick Weil’s new book captures the anger and confusion of the period. His evenness of manner that sets the hysteria of his subjects into high relief; take, for example, Sigmund Freud, who wrote of Wilson: “As far as a single person can be responsible for the misery of this part of the world, he surely is.”

Anger and a certain literary curiosity drove Freud to collaborate with William C. Bullitt, Wilson’s erstwhile advisor, on a psychobiography of the man. His daughter Anna hated the final book, but one has to assume she was dealing with her own daddy issues.

Delayed by decades so as not to derail Bullitt’s political career, Thomas Woodrow Wilson: a psychological study was published in bowdlerised form, and to no very positive fanfare, in 1967. Bullitt, by then a veteran anti-communist, was chary of handing ammunition to the enemy, and suppressed his book’s most sensational interpretations, involving Wilson’s suppressed homosexuality, his overbearing father, and his Christ complex.

In 2014, Weil, a political scientist based in Paris, happened upon the original 1932 manuscript.

Are the revelations contained there enough on their own to sustain a new book? Weil is circumspect, enriching his account with a quite detailed and acute psychological biography of his own — of William Bullitt. Bullitt was a democratic idealist and political insider who found himself pushed into increasingly hawkish postures by his all-too-clear appreciation of the threat posed by Stalin’s Soviet Union. He made strange bedfellows over the years: on his deathbed he received a friendly note from Richard Nixon, “Congratulations incidentally on driving the liberal establishment out of their minds with your Wilson.”

Those readers who’ve come for bread and circuses will find that John Maynard Keynes’s 1919 book “The Economic Consequences of the Peace” chopped up Wilson nicely long ago, tracing “the disintegration of the president’s moral position and the clouding of his mind.” Then there’s the 1922 Wilson psychobiography that Freud did not endorse, though he wrote privately to its author, William Bayard Hale, that his linguistic analysis of Wilson’s prolix pronouncements had “a true spirit of psychoanalysis in it.” Then there’s Alexander and Juliet Georges’ Woodrow Wilson and Colonel House, a psychological portrait from 1956 that argues that Wilson’s father represented a superego whom Wilson could never satisfy. And there are several others, if you go looking.

So, is Madman a conscientious but unnecessary book about Wilson? Or an insightful but rather oddly proportioned book about Bullitt? The answer is both, nor is this necessarily a drawback. Bullitt’s growing disillusion with Wilson, his hurt, and ultimately his contempt for the man, shaped him as surely as his curiously unhappy childhood and a formative political debacle at Princeton shaped Woodrow Wilson.

“Dictators are easy to read,” Weil writes. “Democratic leaders are more difficult to decipher. However, they can be just as unbalanced as dictators and can play a truly destructive role in our history.”

This is well put, but I think Weil’s portrait of Bullitt demonstrates something broader and rather more hopeful: that politics — even realpolitik — is best understood as an affair of the heart.