Watching Ian Cheney’s The Arc of Oblivion for New Scientist, 28 February 2024

“Humans don’t like forgetting,” says an archivist from the Al Ahmed Mahmoud library in Chinguetti. Located on an old pilgrim route to Mecca, Chinguetti in Mauretania is now disappearing under the spreading Sahara. And not for the first time: there have been two previous cities on this site, the first built in 777 AD, and both have vanished beneath the dunes.

Ian Cheney, a documentary maker from Maine in the US, visits the Arabo-Berber libraries of Chinguetti towards the end of a film that’s been all about what we try to preserve and hang on to, born as we are into a universe that seems willfully determined to forget and erase our fragile leavings.

You can understand why Cheney becomes anxious around issues of longevity and preservation: as a 21st-century film-maker, he’s having to commit his life’s work to digital media that are less durable and more prone to obsolescence than the media of yesteryear: celluloid, or paper, or ceramic.

Nonetheless, having opened his film with the question “What from this world is worth saving?”, Cheney ends up asking a quite different question: “Are we insane to imagine anything can last?”

“Humans don’t like forgetting” may, in the end, be the best reason we can offer for why we frantically attempt hold time and decay at bay.

This film is built on a pun. We see Cheney and various neighbours and family friends building an ark-shaped barn in his parents’ woodland, and made from his parents’ lumber. It’s big enough, he calculates that if all human knowledge were reduced to test-tubes of encoded DNA, he could just about close the barn doors on it all.

(The ability to store information as DNA is one of the wilder detours in a film that delights in leaping down intellectual and poetic rabbit holes. The friability of memory, music and memory, ghost stories, floods and hurricanes — the list of subjects is long but, to Cheney’s credit, it never feels long).

Alongside that Ark in the woods, there is also an arc — the “arc of oblivion” that gives this film its title, and carrying the viewer away from anxiety, and into a more contemplative and accepting relationship with time. Perhaps it is enough, in this life, for us to be simply passing through, and taking in the scenery.

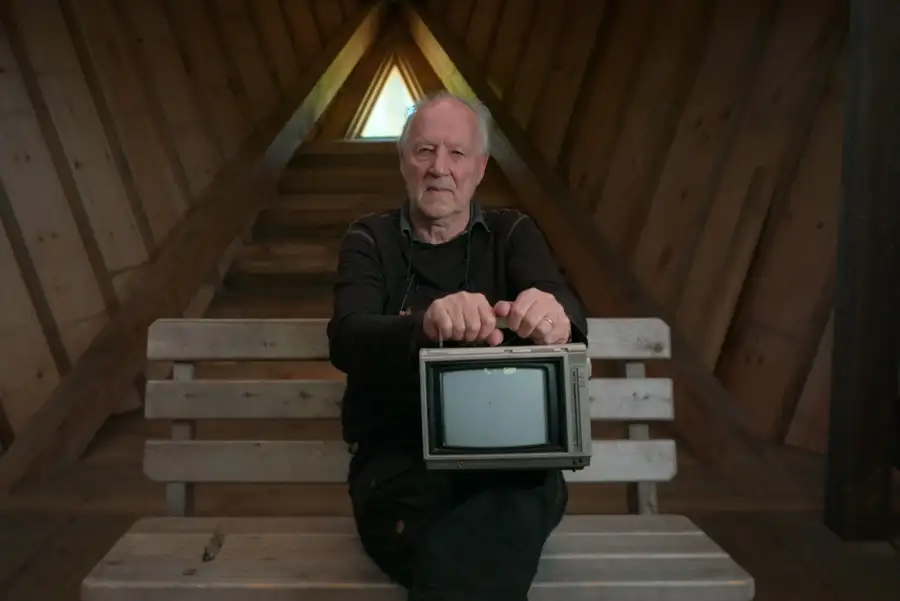

Executive producer Werner Herzog, a veteran filmmaker, appears towards the end of the movie. Asked why he destroys all the preparatory materials generated by his many projects, he replies “The carpenter doesn‘t sit on his shavings, either.”

This is good philosophy, and sensible practice for an artist — but it’s rather cold comfort for the rest of us. At least while we’re saving things we might be able to forget, for a moment, about oblivion.

If human happiness is what you want, then the trick may be to collect for the pure pleasure of collecting. Even as it struggles to preserve Arabo-Berber texts that date back to the time of the Prophet, the Al Ahmed Mahmoud library finds time to accept and catalogue books of all kinds donated by people who are simply passing through. We also meet speliologist Bogdan Onuc, who traces the histories of Majorcan caves by studying their layered deposits of bat guano (and all the while the caves’ unique interiors are being melted away by the carbonic acid generated by visitors’ breaths…) But Onuc still finds time to collect ornamental hedgehogs and owls.

Cheney’s cast of friends and acquaintances is long, and the film’s discursive, matesy approach to their experiences — losing photographs, burying artworks, singing to remember, singing to forget — teeters at times towards the mawkish. The Arc of Oblivion remains, nonetheless, an enjoyable and often moving meditation on the pleasures and perils of the archive.