Chasing an old adversary through a world containers made; salvaged from Arc magazine

1

It’s Christmas 2006 and I’m walking beside the creek in Dubai. The pavements and central reservations teem with tourists and Russian prostitutes in roughly equal numbers. Tied up six deep at the quay, dhows are being packed to the gunwales with second-hand Toyota Hiluxes. Piles of tyres, plucked off wrecked and defunct cars, are being hauled by hand into the rusted holds of boats bound for retreading factories in Navlakhi and Karachi. From China, mattresses. Piles of flashlights. Chairs, tables, oxytetracycline injections. Chilean softwoods. Foam mattresses. Drums of sorbitol from Mumbai.

Container shipping serves the great ports of the earth, but there are few enough of

them, and none in north Africa. With no deep harbours, the region depends on little ships like these. The scene fills me with an intense (though false) nostalgia. It’s an echo of the way shipping used to be, as recorded in the writings of my literary heroes. Joseph Conrad, James Hanley, Malcolm Lowry…

Patrick Hamilton: at the end of The Midnight Bell, Bob, defrauded and betrayed, stares across the Thames. The river runs beneath him, “flowing out to the sea…

“The sea! The sea! What of the sea? “The sea!

“The solution – salvation! The sea! Why not? He would go back, like the great river, to the sea!”

This is not suicide. This is a career move.

“He had wasted enough time. He would go down to the docks now, and see what was doing. Now! Now! Now!”

Now, of course, is too late. It used to take days to unload a ship and a ship’s crewmen could spend most of this time resting and drinking and whoring themselves silly on shore. Such capers are relegated to the storybooks now. These days, time in port is measured in hours; junior officers pull twelve-, even eighteen-hour shifts, and regular seamen like Bob (these days a Bangladeshi or Malay) are rarely allowed off the ship. These days, a crew works itself to exhaustion in harbour and spends the voyage recuperating.

Since April 1956 the shipping container has been ushering in a more ordered world. No stench, no sweat. No broken limbs. No sores, no sprains. No ham-boned supermen rolling drunk on Friday night on wages their children never see.

This new, clean, modular world arrives in boxes. From port to port, big, square-built ships carry ever bigger quantities of it about the earth. Great cranes lift it and deposit it on truck beds and railway cars. It is borne inland to every town, every settlement. Ships were once shackled, constipated, squeezing out their goods for weeks on end on the backs of men made beasts. Today they evacuate themselves in hours.

The shipping container was developed by Malcolm McLean, an American entrepreneur who realised his trucking business was being undercut by domestic shipping. After the war, you could buy a war-surplus cargo ship for next to nothing. “Jumboize” it by adding a German-made midsection, and you had a craft capable of moving goods more cheaply than road or rail. The only drawback, before McLaren, was trying to get your goods on and off the vessel. That consumed time and labour enough to represent half your costs – even if you were carting products halfway round the world.

Standardised containers, and the machinery developed to juggle them, can now disgorge vessels a fifth of a mile long in hours.

Two-hundred-foot-high cranes reach across ships broader than the Panama Canal. Some of the more powerful commercial computer applications on the planet ensure that goods are stacked in the right order, in the right containers, in the right section of the right hold of the right ship plying the right route to ensure that these goods are delivered at the right place at the right time. The drive to efficiency has squeezed schedules to the point where Ford and Walmart and Toyota are wholly dependent on timely deliveries for their operation. If their boxes are more than a few days late, they go into hibernation.

Logistics used to be a military term. Now it’s a core function of business. By stripping the fat and inefficiency out of its resource chain, developed Western commerce has placed itself on a permanent war footing. And the war goes well. The variety of goods the First World consumes has increased fourfold, while expanding markets have brought economic and social benefits, however unevenly, to the poorest people on the planet.

Like the fatuous “War on Terror”, however, this is an open-ended conflict: we will never know when we have won it. At what point does an industry’s athleticism start to undermine its health? At what point does a strict diet bloom into galloping anorexia?

2

Construction in the Persian Gulf stops

altogether in summer, when the skies are white and people (if they’re outside at all, which is seldom) huddle in pitiful scraps of shade. Even the more temperate months prove too much for some. The furnace light, the dust, the scale of things.

July 2009. A fence, not much higher than a man and topped with razor wire, runs rifle straight beside the road all the way to a granular horizon. Behind the fence stretch mile after mile of prefabricated houses. The narrow lanes between them are slung with clothes lines. Construction workers sit knocking pallets together. Here and there mounds of graded gravel rise in parody of the great ranges to the south. The road has begun to disintegrate, its surface crazed and sunken under the weight of so many trucks bound for Dubai with loads of boulders and gravel. The World and The Palm began life here, as the insides of mountains.

I come to a roundabout. There is a fountain at its centre: a dry cement tower clad in blue swimming-pool tile, sterile as a bathroom fitting. There isn’t a hint of what places the roundabout might one day serve. No buildings. No traffic. No signs. Just a tarmac sunburst in the sand, its exits blurred and feathered by encroaching dust. On the horizon there are whole city blocks that aren’t even on a map yet. New

developments, bankrolled by the Saudis. University cities thrown up at miraculous speed by Bangladeshi guest workers. Fawn crenellations hover inches off the horizon on a carpet of illusory blue.

It’s late afternoon by the time I find my way back to the city. My hotel room in Dubai has hyperactive air conditioning, a view of the Emirates Towers, and Miami Vice reruns on an endless loop.

In an episode entitled “Tale of the Goat” nobody seems to know whether to take the plot seriously or not. One minute Crocket is joking about voodoo, the next he’s taking advice on Haitian religious practices from Pepe the janitor.

He’s right to be worried. Papa Legba, a Haitian voodoo priest, has faked his own death, been buried, disinterred, and shipped in his coffin to Miami, all to take revenge on a business rival. Clarence Williams III’s portrayal of Papa – brain damaged, half-paralysed, sickeningly malevolent – kicks a hole in the TV big enough for the nightmares to slip out.

People do this kind of thing for real. In 1962 the Haitian petty speculator Clarvius Narcisse was poisoned, buried alive, dug up and drugged into believing that he was a zombie.

Notoriously, shipping containers have cleaned up and expanded even the business of self-burial. Vanishing into a box has never been simpler. According to figures from the United Nations, in 2007 slave traders made more money than Google, Nike and Starbucks combined, their global logistics smoothed by the advent of container shipping.

Incarceration doesn’t even have to be uncomfortable. Five weeks after the September 11 attacks, a dockworker in the Italian container port of Gioia Tauro discovered a stowaway inside a container appointed for a long voyage. There was a bed, a heater, a toilet and a satellite phone. The box, bound for Chicago via Rotterdam and Canada, was chartered by Maersk Sealand’s Egyptian office and loaded in Port Said onto a German-owned charter ship flying an Antiguan flag. Where the stowaway was bound is anyone’s guess. Incredibly, he was granted bail and vanished, abandoning his cellphone, his laptop, airport security passes and an airline mechanic’s certificate valid for Kennedy and O’Hare.

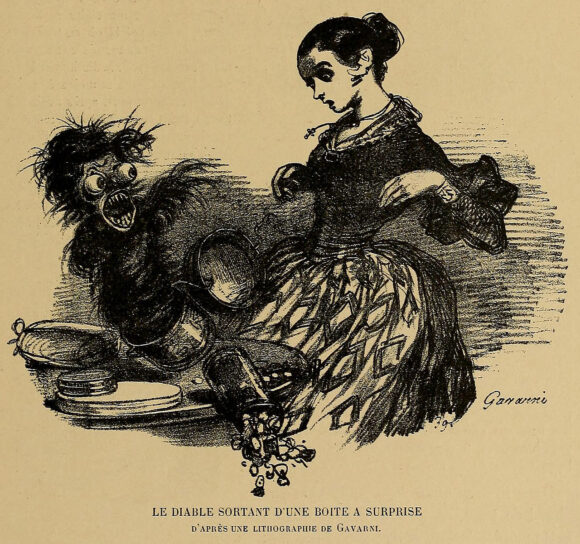

It’s an old nightmare, perhaps the oldest: waking up inside a sealed coffin. The strange voyage of “Container Bob” epitomises its flipside: fear of what leaps out at you when you prise the lid open. This too is an old anxiety; so old, the words that express it no longer line up properly. Pandora’s box was actually a jar (a ritual container for the dead, as it happens, so the frisson survives the mistranslation.) And the first jack-in-the-box hid in a boot. The English prelate Sir John Schorne was supposed to have cast the devil into a boot some time in the 1200s, saving the village of North Marston in Buckinghamshire from perdition.

Since then the “diable en boîte” has been springing out at us at the least expected moments, maturing from a crank-operated children’s toy in the 1500s to a pyromanic McGuffin in director Robert Aldrich’s nuclear noir Kiss Me Deadly, to a headline grabbing red herring at international security conferences. (The “suitcase nuke” is still a myth, though one creeping uncomfortably close to reality: backpack nukes have been around since the 1970s.)

The shipping container is, according to security analysts, the old devil’s current mode of transportation. Why would the world’s whirling axes of evil go to all the trouble of developing an intercontinental ballistic missile when a container can do the same job, more accurately and over a greater distance, for under $5000?

Around 150 companies in the US alone – from tiny start-ups to giants like IBM – are using technical fixes to plug Homeland Security’s very real fear of a container delivered chemical, biological or nuclear attack on the US mainland. With more than two million steel and aluminium boxes moving over the earth at any one time, the scale of the work is Herculean: to fit tamper proof sensors providing real-time geolocation data on every can on earth. Meanwhile America’s megaport Los Angeles/Long Beach unloads its containers in long parallel rows, like trains. An imaging machine mounted on tall steel legs trundles over them. The machines are popular, but they’re not without flaws. Concealed nuclear bombs are not the only sources of radiation on the dockside. There are ceramic tiles. There are bananas. Caesium and cobalt are famously hard to distinguish from kitty litter. And the more sensitive the detectors, the more false positives the port authority has to handle.

In any open-ended conflict, the enemy we most have to fear is fear itself: our crippling overreaction to false positives. It is more than possible, in a system lean enough to admit no delay, that the entire world economy can and will hoax itself to a standstill.

3

It’s 2011 and I’m making a third and final visit to Dubai, a city the old boys remember as a ramshackle fort overlooking a malarial creek. The city’s “miracle” is more or less complete. The transformation looks sudden, but it’s been forty years in the making. In the 1970s, when towns like Abu Dhabi were allowing their harbours to silt up, confident that all the wealth they could ever need would well up out of the ground forever, oil-poor Dubai was dredging its harbour and encouraging imports. Now it’s a vital entrepot for former states of the Soviet Union: people hungry for everything, from plastic plates and toys to polyester clothing, much of it manufactured in the Far East and India.

The major part of this traffic is

containerised and handled by machines outside the city proper, in Port Rashid and Jebel Ali. The road out to these deep-water megaports is lined with private clinics: plastic surgeries catering to the city’s sun frazzled Jumeira Janes. Dubai maddens people. Never mind the heat. Since the global recession, the advertisements on Dubai’s innumerable hoardings and covering entire faces of its complete-but empty high-rises have grown even more extreme in their evocation of the city’s dream-logic.

“Live the Life.”

“We’ve set our vision higher.”

Even the white-goods retailers have names like Better Life and New Hope. Aspiration as an endless Jacob’s ladder. Perfect your car, your phone, your home, your face. Perfect your labia. Plastic surgeons line the way to erotically sterile encounters at the Burj al Arab hotel. Then what? Then where? The elevators only go up. Take a helicopter ride into the future. Cheat death. Chrome the flesh. Every advert I ride past features a robot. A perfected man. A smoothly milled thigh or tit. A cyborg sits at the wheel of the latest model four-wheel drive, limbs webbed promiscuously around the controls. A mobile phone blinks in a stainless steel hand.

The shipping business still fascinates me, and researching it continues to swallow the freelance budget. This will have to stop.

For a start, Dubai feeds fantasy. Every once in a while an attic in the Old Town, Deira, is raided by armed police. A man is led away, or sometimes shot. Every now and again, a headless corpse is found slumped in a pool of blood in one of the city’s many subterranean car parks, and children fishing in the creek watch as a heron rips beakfuls of hair from the remains of a human head. In Dubai, everyone is anonymous and significant at the same time. It’s Casablanca. It’s Buenos Aires. A loser’s paradise.

For another, my ill-financed pursuit of Sir John Schorne’s devil has taken new twist. He has swapped vehicles yet again. I missed this at the time, but while I was watching Crockett and Tubbs reruns, over 75,000 others were waking to one of YouTube’s more piquing viral crazes: a video of a man opening a box. Uploaded On 11 November 2006, this video – a so-bland-as-to-be transgressive record of a 60GB Japanese PS3 gaming console being removed from its cardboard and polystyrene packaging – is the earliest extant example we have of “unboxing”.

The Wall Street Journal rightly picked up on the genre’s striptease pedigree, but it missed, I think, the greater part of the video’s appeal. CheapyD Gets His PS3 – Unboxing is, above all, a comprehensive attempt to disarm the anxieties conjured by Jack’s unexpected springing from his box. In the video, a carton is opened slowly and steadily under controlled conditions to reveal exactly what the packaging said it would contain.

The cardboard carton is the disposable, end-user-friendly leaving of the shipping industry. Men who might once have tugged and trawled the world’s plenty about its rumbling yards with case hooks now haul goods ordered off the internet about our residential streets: careless and savage, they crush our precious parcels through diminutive letter boxes, miniscule slots cut for a different, more genteel age.

When people talk about shipping, they talk about goods. They talk about televisions and motorbikes and cars and toys and clothing and perfumes and whisky. The more informed discuss screws, pigments, paints, moulded plastics, rolls of leather, chopped-glass matting, bales of cotton, chemicals, dyes, yeasts, spores, seeds, acids and glues. The paranoid occasionally mention waste. The single biggest global cargo by volume is waste paper, closely followed by rags and shoes, soft-drinks cans, worn tyres, rebars and copper wire. The containers themselves escape notice.

They are the walls of our world. In less than a single generation, they have robbed us of two-thirds of the earth’s surface. The sea has been stolen away by vast corporations, complex algorithms, robot cities, and ships as big as towns. Everything ends up in a box these days and the world has become a kind of negative of itself: not an escape, but a trap.

The real appeal of CheapyD Gets His PS3 – Unboxing is that it doesn’t just disarm the jack-in-the-box game. It damn near reverses it. The contents of the box are irrelevant: a final bolus of processed matter for us to scrabble past as we struggle towards rebirth. We are all Jacks now, compressed by our own logistics, imprisoned in the rhetoric of war, crippled with anxiety, our brains rotten with it, and ready to spring, if only we could find the catch to this lid.

CheapyD’s next trick – five years, we’ve waited to see this, what is taking him so long? – will be to escape. To jump into his box, and disappear.