Writing is dark magic. Because the written, or even better, carved, word can effortlessly outlive the human span, it enables the dead to lord it over the living.

There are advantages to this, of course. It’s handy not to have to reinvent the wheel generation after generation.

But let’s be clear who wields the power here – much as the ancient Egyptians, who used to channel the divine power of words into spells that would animate carved servants, or shabti, ready to do their bidding after their death. “Here I am,” reads the inscription on one poor put-upon shabti, ready “when called to work, cultivate fields or irrigate the riverbanks.”

Poetry be damned: writing is first and foremost about control.

This is very apparent in a new exhibition at the British Library, London, called Writing: Making your mark. It’s been launched to celebrate a technology that’s a bit under five millennia old, so you’ll find everything from carved stone slabs to the first ever use of an italic typeface, to (my favourite) an eye-wateringly vituperative telegram (in four parts) from the 20th century British playwright John Osborne to a hostile critic.

It’s comprehensive, thoughtful and eye-catching, with a design that has you wandering through what looks like some peculiar 3D cuneiform from the future. Best of all, the show makes narrative sense: we learn how various writing and printing forms evolved independently at different times and places, to fulfil changing social and cultural functions.

Granted, the story does not and cannot start with much of a bang. As the wall information concedes, the act of writing is just a recreational by-product of accounting. The first written records were tallies, calendars and contracts. Set aside their great age and the earliest objects in the exhibition (among them the oldest in the Library’s collection, an Egyptian stela (carved stone) from around 1600 BC) make for dull reading.

But amazingly early, suspicion, and even downright hatred, of the written word crept in – to run like a secret history beneath the course of Western culture. In the dialogue Phaedrus, composed around 370 BC, the ancient Greek philosopher Socrates complains that writing things down will “create forgetfulness in the learners’ souls, because they will not use their memories; they will trust to the external written characters and not remember of themselves… they will be hearers of many things and will have learned nothing”.

Plato, Socrates’ pupil, listened to his master’s diatribe intently. Indeed, he took down every word. Plato’s obtuse disobedience has paid huge dividends. For one thing, it means that Socrates’ wisdom is available to us all. Millennia hence, we are still reading Phaedrus, and smiling at the quaint bits.

But a few of us (we meet in dank basement rooms: check your pens and smartphones at the door) agree with Socrates. We reckon that putting pen (stylus, chisel or moveable type…) to paper (stone, slate, clay, or peeled bark) has set the lot of us on the road to everlasting perdition.

Our current all-too-well founded panics around trust, authority, truth and fake news feed the gloomy suspicion that the written word makes us lazy and shallow, that for all our modern, information-driven wonders, our space rockets and our antibiotics, it makes us less than we might be: a people earnestly conversing with themselves.

Writing: Making your mark does its best to win us round to the cause of literacy and preserved thought.

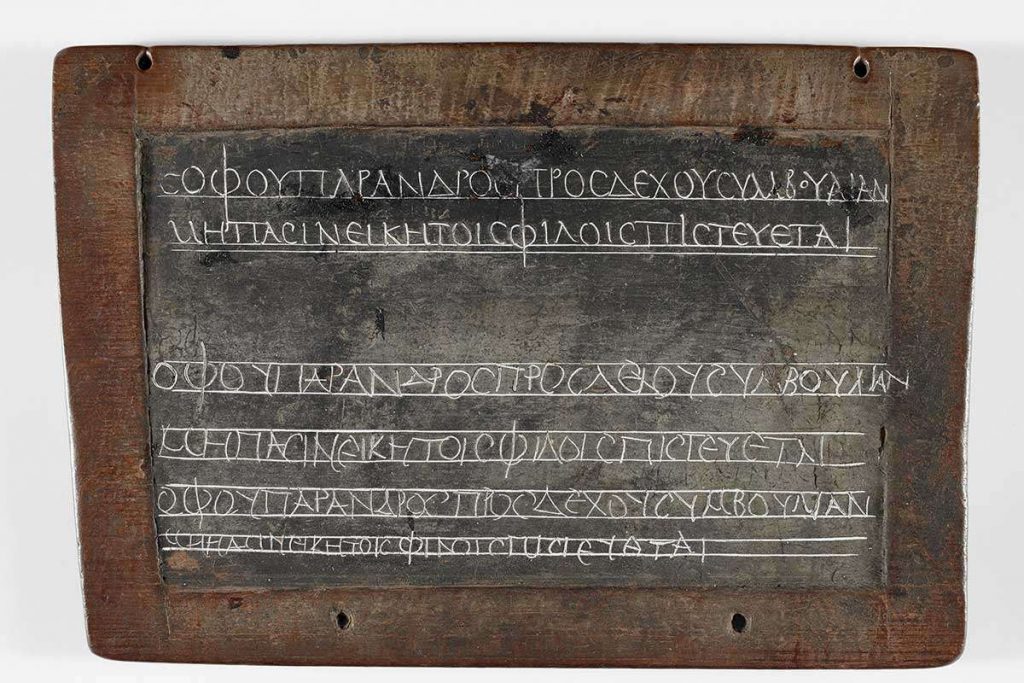

Who knew that the story of written forms would prove so epic? Or, indeed, so touching? There’s a sandstone sphinx sporting a prototype letter “A”, and a Greek child’s second-century homework scratched, laboriously, on a clay tablet.

But with their final room, about the future of writing, I feel the curators may finally have woken to doubt. A black box, and virtually empty, this space whether new media may undercut our surprisingly resilient written culture.

I’m surprised the curators’ confidence should have been so shaken. After all, written and printed forms continue to proliferate: emoji have provided us with a whole new writing system to combine with our alphabetic language. Instagram, once the home of unadorned selfie snaps, now wobbles and sparkles with photos smothered in animated annotations and one-liners in a form that’s so new it hasn’t really got a name yet. Writing continues to be one of our most plastic and fast-changing forms of self-expression.

Though with each innovation, we retreat, chattering, ever further from Socrates’ dinner party ideal of society driven by good conversation.