Reading Foreign Bodies by Simon Schama for the Financial Times, 9 June 2023

Right up until the middle of the 19th century, huge deposits of steaming human ordure were carted out of Paris and over the channel to fertilise the fields of England. And good riddance to the stuff, since letting it rot in place would surely have produced a miasma responsible — so most Parisians thought — for everything from smallpox to cholera to bubonic plague.

But Julien Proust (Marcel’s father) realised that there was something wrong with this picture. Even before the germ theory of disease gained currency, Proust conjectured that infection spread, not so much through proximity to decomposing matter, but by its being transported, most likely by people. As Schama puts it: “the very means used to bind the parts of empires more closely – shortening distances, abbreviating shipping schedules, reducing costs, optimizing profits, doing things the modern way – had themselves become the flowing conduits of disease and death.”

Proust is one of a pantheon of heroes (and I do not use the ‘H’ word lightly) propelling Simon Schama’s epic and impassioned history of vaccination from disconcertingly ancient times to the vexed present day.

His book, says Schama, is one more product of the Covid-19 lockdowns, when “parliaments of legislators were reduced to socially distanced barking from the hollow shell of their chambers, while parliaments of birds flocked and chattered.”

While the rest of us were enjoying (at least as far as we could) the birdsong, Schama was contemplating what Covid-19 represents for the planet. His conclusion is: nothing good. The waves of terrifying diseases coming at the world faster and faster are almost always transmitted by animals, and “mutuality between humans and animals has been dangerously disrupted.”

Schama has an historian’s tragic view of life, exacerbated here by his having (like the rest of us) to chain himself to his home office. From here the rise and fall of civilisations have seemed to him “so many vanity projects compared to the entropy of the habitable planet”.

Schama is far too interested in people to spin this apocalyptic jag too far. Soon enough he gets stuck into the stories of the men and women who, confronted by contagion, have tried, and still try (often against rabid opposition — and I don’t use the ‘R’ word lightly, either) to do something about it.

Though Schama’s richest materials here are to do with vaccination,

Foreign Bodies ultimately tilts at a bigger target: how medical knowledge and political force intersect to fight epidemic disease. And when your fatality rates reach ninety per cent, as they did when bubonic plague struck Hong Kong in 1894, you can bet that force will be pretty much your only weapon. Whole neighbourhoods of Kowloon were walled off as British soldiers pulled sick family members out of hiding in closets and chests and bore them off to the Hygeia, rumoured to be a death-ship from which not one in ten would emerge alive. (“This was in fact true.”)

In India, facing the same death toll and the same desperate, militarised sanitation campaign, rumours spread that hospitals had been ordered to cut out the hearts of patients to send to Queen Victoria for her vengeful satisfaction.

This is why, even at some cost to life, governments fight shy of making life-saving treatments compulsory: a show of force invariably does as much damage as the disease. Ronald Reagan understood this: “The nine most terrifying words in the English language are: ‘I’m from the Government, and I’m here to help’” he once quipped — though I doubt that he had in mind scenes as apocalyptic as Schama’s.

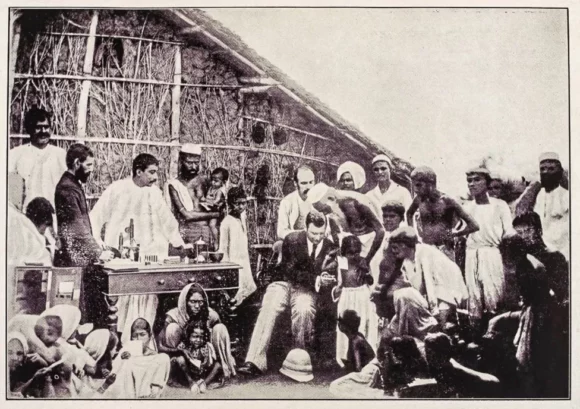

With the aplomb of a young A. J. P. Taylor, Schama neatly balances the obligation to disparage empire with the historian’s love of valorous action. He pricks the pretensions of the Raj, whose grandees thought they had materially bettered the lives of Indians; but he handsomely acknowledges the human efforts expended, in crowded slums and roadside clinics, pursuing that fond vision.

“Something about inoculators, vaccinators and epidemiologists gets under the skin of public tribunes,” frets Schama, “for whom nothing, certainly not epidemiology, is politics-free.”

Might future historians see Anthony Fauci, who as Chief Medical Advisor saw the US through AIDS and Covid, as some sort of imperial shill? They will if they ponder the fulminations of (now former) Fox news anchor Tucker Carlson, who had Fauci down as “a dangerous fraud who has done things that in most countries at most times in history would be understood very clearly to be very serious crimes.”

Compared to what Fauci’s been put through, the British establishment’s treatment of Foreign Bodies’ central figure, the fin-de-siecle vaccine pioneer Waldemar Haffkine, seems positively benign. Haffkine, a Jew from Odessa without so much as a medical degree, wanted to totally upend the Indian Medical Service’s handling of epidemics, replacing brutal quarantine measures with vaccines, mostly of his own devising. Not only did he come up with the first vaccine against cholera (and inoculated nearly 23,000 in his first year in India); by the spring of 1899, a Haffkine serum was protecting half a million Indians against bubonic plague and was being shipped as far afield as Russia. Incredibly, one locally contaminated batch ruined the man’s career and scotched his global plans.

Or maybe not so incredibly: our politics have hardly grown more forgiving, as any AstraZeneca executive involved in the Covid response can tell you.

“Falsely accused scapegoats recur with depressingly predictable regularity in the long history of inoculation,” says Schama. “They are often demonised as the bringers of false hope, the reckless spreaders of contagion, sometimes even secret spies or enemies of a Nation’s health.”

Vaccination is a wildly counter-intuitive process. “It is,” says Schama, “an extraordinary leap of faith for a healthy person or a parent of a healthy child to expose themselves or their offspring to what is essentially a toxin.”

So it is that in each generation, in the face of each new emergency, the powerful have a choice: gamble on hard-won, hard-to-explain knowledge — or appeal to native instinct. And if you want to be told that knowledge and decency win out every time, well, Schama says it: “it is probably best not to ask an historian.”