Butcher’s Hook

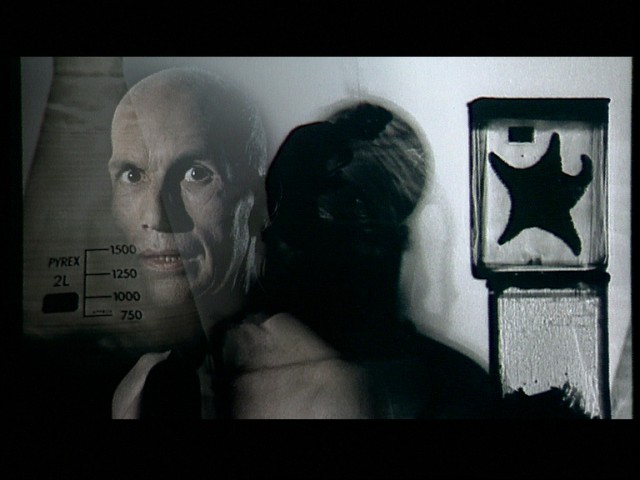

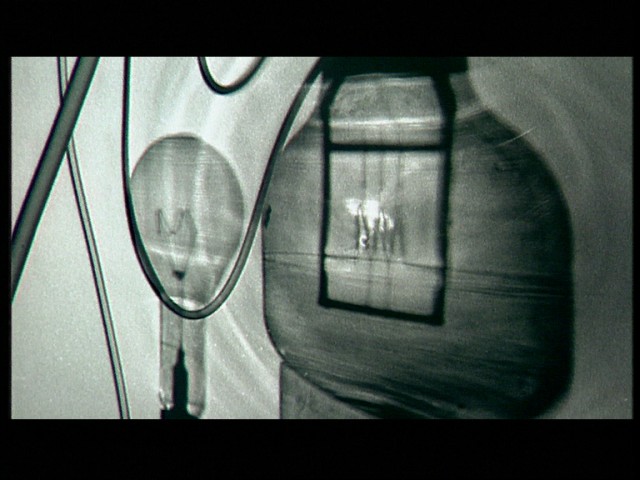

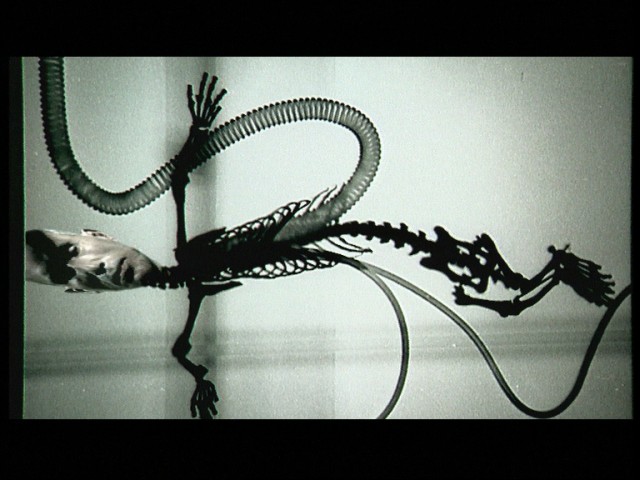

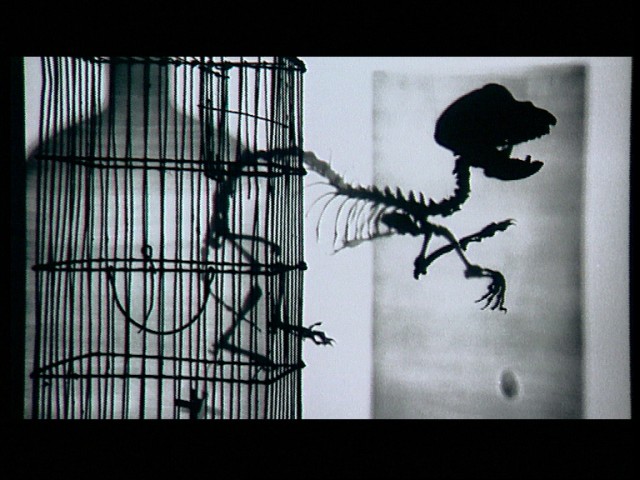

dir. Simon Pummell (http://www.pummell.com/), BFI/BBC, 1996

I wrote the scenario.

Rose Red

dir. Simon Pummell (http://www.pummell.com/), BFI/Channel4, 1994.

Best of the BFI’s recent films is Rose Red, a high-tech sci-fi mystery that addresses anxieties about surveillance, virtual reality, addiction and lethal viruses.

Time Out

In 2025, a detective’s investigation of a drug theft forces him to explore his dark side. Black and white dream sequences of the detective as an innocent boy contrast with the clinical future setting. The Rose Red of the title is a drug used to switch off the body’s immune system so that people can jack into computers without the body rejecting the experience with fatal consequences.

I co-wrote the screenplay for this with Simon Pummell. Interviewed by David Mathew in 2000, I explained the film this way: “My first novel, Hothead, was how I came to work with a director, Simon Pummell, with whom I did a few short films. He fell in love with my meat trees. And I was already thinking about stripping things back so that somebody could put a 13-amp plug in their head. We ended up doing a 30-minute cyberpunk thriller, Rose Red, which got made. It then got expanded into a feature film, which we wrote, which went into development, which we actually got paid for, but never got made — for various budgetary considerations, and because, basically, it was terrible…

“One of the reasons it didn’t work, and why no cyberspace film ever works, is that you can’t film cyberspace. If it’s going to be a heavenly place, a transcendent place, then it’s certainly going to have to transcend 35mm film! The best you’ll ever be able to do is shine a bright light into the camera and hope that the audience have some imagination. It’s much easier to do it in fiction. Which is ironic, considering the fatal fascination it’s had for filmmakers over the last 10 years. People have joyously leapt off the cliff, like so many lemmings. The better the film technology gets, the worse the films seem to get — again, ironically enough. There’s probably a lot to be said for keeping things simple; for encouraging the imagination, and not showing everything there is to be shown…”

Rose Red

The Weight of Numbers

On July 21, 1969 two astronauts set foot on the moon; far below, in ravaged Mozambique, a young revolutionary is murdered by a package bomb.

Strung like webs between these two unconnected events are three lives: Anthony Burden, a mathematical genius destroyed by the beauty of numbers; Saul Cogan, transformed from prankster idealist to trafficker in the poor and dispossessed; and Stacey Chavez, ex-teenage celebrity and mediocre performance artist, hungry for fame and starved of love. All are haunted by Nick Jinks, a man who sows disaster wherever he goes. As a grid of connections emerges between a dusty philosophical society in London and an African revolution, between international container shipping and celebrity-hosted exposés on the problems of the Third World, The Weight of Numbers sends the spectres of the baby boom’s liberal revolutions floating into the unreal estate of globalization and media overload—

You can pick up a paperback of The Weight of Numbers at Amazon.co.uk. Anyone who wants the first edition can fill their boots here

. And there’ll be a Kindle version along in a little while.

Lunacycorp

My only foray into the art world: a collaborative installation for Punchdrunk’s Tunnel 228. Click the picture for more.

Elephants on Acid and Other Bizarre Experiments by Alex Boese

There is a connection between vaudeville and science, and it is more profound than people credit. Alex Boese’s collection of bizarre scientific anecdotes illuminates this connection, claims far too much for it, and loses the thread of it entirely.

This probably doesn’t matter – by Boese’s own estimation, Elephants on Acid is a book you dip into in the bathroom. There’s even an entire chapter, ‘Toilet Reading’, dedicated to this very idea.

But Boese, quietly meticulous, is a champion of the idea of science. So, at the risk of taking a mallet to a sugar-coated almond, let’s take him seriously here.

Boese is the curator of a splendid on-line museum of hoaxes – museumofhoaxes.com. To move from deliberate fakery to science gone awry, deliberately or not, is, Boese argues, but a small step.

Hoaxers and experimenters are both manipulators of reality. But only experimenters wrap themselves in the authority of science. ‘This sense of gravity is what lends bizarre experiments their particularly surreal quality.’ More charitably, he might have added: only scientists run a serious and career-busting risk of hoaxing themselves.

Boese’s accounts of unlikely experiments include sensible and legitimate studies into risible subjects (how could studies into human ticklishness not sound silly?) Elsewhere, accounts of doubtful ‘discoveries’ reveal how badly credulousness and ambition will misdirect the enquiring mind.

Wandering among Boese’s carnival of curiosities we learn, for example, the precise weight of a human soul and acquire a method for springing crystalline insects out of rocks.

Less convincing are his stories of research misinterpreted by gullible or hostile media. A sharper editor would have spotted when Boese’s eye for a good tale was leading him astray.

In 1943 the behaviourist Burrhus Skinner invented a comfortable, labour-saving crib for his baby daughter – only to be pilloried for imprisoning her in an experimental ‘box’. This is a tale of irony and injustice, deftly told. But it is not ‘bizarre science’.

It’s devilishly difficult to get good at something unless you can find the fun in it. The more intellectually serious a work is, the more likely it is to have playful, even mischievous aspects. Science is no exception.

The more entertaining, and less troubling, of Boese’s tales involve ingenious, self-aware acts of scientific folly. We learn a truly magnificent (and wrong) formula for working out the moment at which cocktail parties become too loud.

A study that involves erotically propositioning young men on a wobbly bridge must surely have fallen out of the bottom of an Atom Egoyan movie. And pet owners should heed a slapstick 2006 study entitled ‘Do Dogs Seek Help in an Emergency?’ (‘Pinned beneath the shelves, each owner let go of his or her dog’s leash and began imploring the animal to get help from the person in the lobby.’)

Yet, for all its hilarity, Elephants on Acid proves to be an oddly disturbing experience when read cover-to-cover.

The decision to put all the truly gut-wrenching vivisection stories in the first chapter was foolhardy. Robert White’s 1962 attempt to isolate a monkey’s brain by removing, piece by piece, the face and skull, absolutely belongs in this book – but it is delivered so early that it’s one hell of a hurdle to clear in the first five minutes of reading.

Other horrors lurk in wait for those who persevere (Ewen Cameron’s brainwashing experiments of the 1950s are particularly horrendous). Boese’s off-the-cuff observation that the Cold War had its surgical and psychological aspects is not staggeringly original but it does mollify our easy outrage at such past ‘mistakes’.

Quite rightly so, for most of what we primly label ‘maverick science’ is no such thing; it is simply science that served a long-since-vanished purpose.

Most disturbing of all, however are those celebrated and familiar behavioural experiments that, while harming no one, reveal human gullibility, spite, vanity and witlessness.

Philip Zimbardo’s prison-psychology experiment at Stanford University had to be terminated, so keenly did his volunteers brutalise each other. Testing the limits of obedience (clue: there aren’t any), Stanley Milgram invited volunteers to inflict what they thought were potentially lethal electric shocks to people. Few demurred. Ironically, these kinds of experiments share methods with many stage magic routines.

The connection between vaudeville and science is profound, all right – and not particularly funny. Boese is right to invite us to dip in and out of his book. His facetious mask cannot hide for long the underlying seriousness of such striking material.