Four books to celebrate the centenary of Eddington’s 1919 eclipse observations. For The Spectator, 11 May 2019.

Einstein’s War: How relativity triumphed amid the vicious nationalism of World War I

Matthew Stanley

Dutton

Gravity’s Century: From Einstein’s eclipse to images of black holes

Ron Cowen

Harvard University Press

No Shadow of a Doubt

Daniel Kennefick

Princeton University Press

Einstein’s Wife: The real story of Mileva Einstein-Maric

Allen Esterson and David C Cassidy; contribution by Ruth Lewin Sime.

MIT Press

On 6 November 1919, at a joint meeting of the Royal Astronomical Society and the Royal Society, held at London’s Burlington House, the stars went all askew in the heavens.

That, anyway, was the rhetorical flourish with which the New York Times hailed the announcement of the results of a pair of astronomical expeditions conducted in 1919, after the Armistice but before the official end of the Great War. One expedition, led by Arthur Stanley Eddington, assistant to the Astronomer Royal, had repaired to the plantation island of Principe off the coast of West Africa; the other, led by Andrew Crommelin, who worked at the Royal Greenwich Observatory, headed to a racecourse in Brazil. Together, in the few minutes afforded by the 29 May solar eclipse, the teams used telescopes to photograph shifts in the apparent location of stars as the edge of the sun approached them.

The possibility that a heavy body like the sun might cause some distortion in the appearance of the star field was not particularly outlandish. Newton, who had assigned “corpuscles” of light some tiny mass, supposed that such a massive body might draw light in like a lens, though he imagined the effect was too slight to be observable.

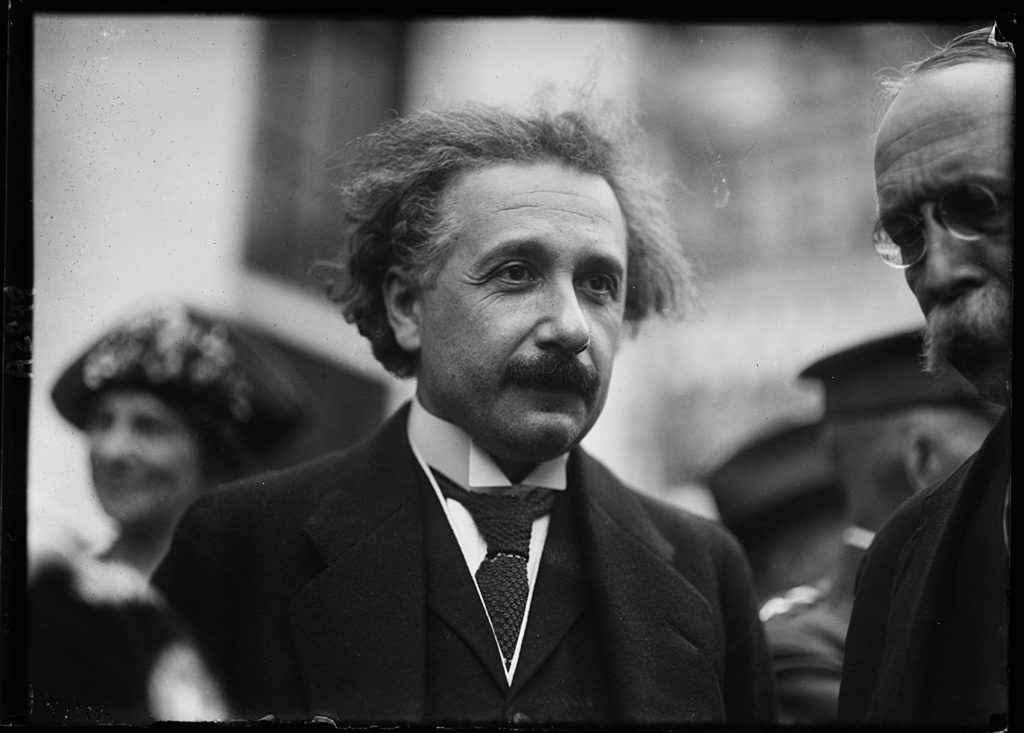

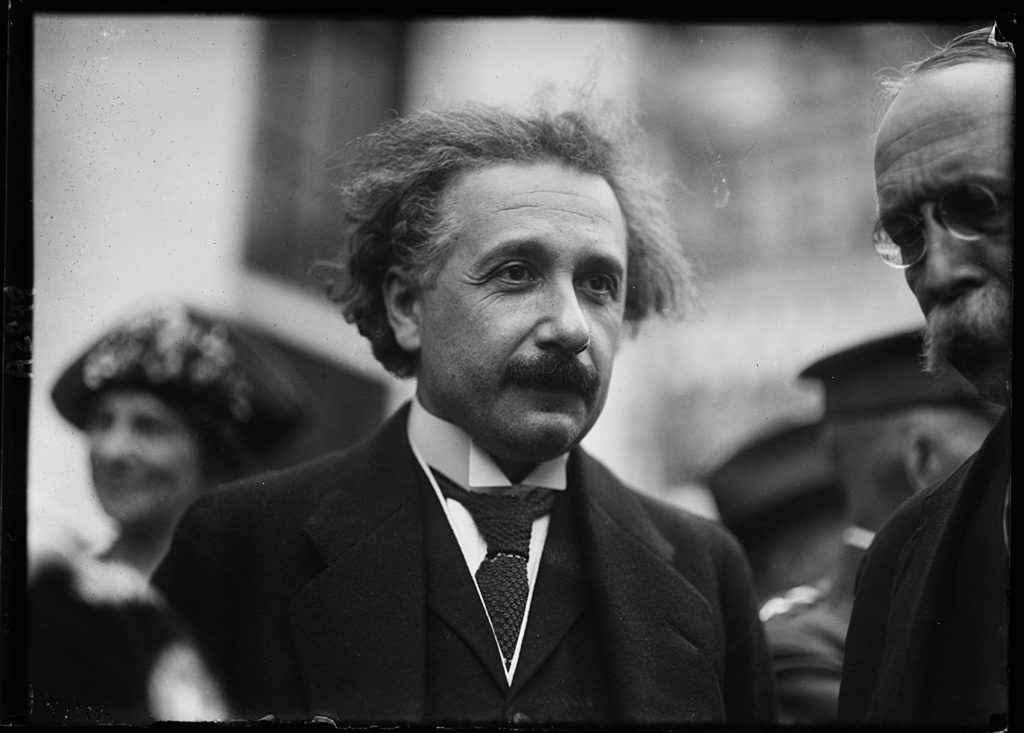

The degree of distortion the Eddington expeditions hoped to observe was something else again. 1.75 arc-seconds is roughly the angle subtended by a coin, a couple of miles away: a fine observation, but not impossible at the time. Only the theory of the German-born physicist Albert Einstein — respected well enough at home but little known to the Anglophone world — would explain such a (relatively) large distortion, and Eddington’s confirmation of his hypothesis brought the “famous German physician” (as the New York Times would have it) instant celebrity.

“The English expedition of 1919 is ultimately to blame for this whole misery, by which the general masses seized possession of me,” Einstein once remarked; but he was not so very sorry for the attention. Forget the usual image of Einstein the loveable old eccentric. Picture instead a forty-year-old who, when he steps into a room, literally causes women to faint. People wanted his opinions even about stupid things. And for years, if anyone said anything wise, within a few months their words were being attributed to Einstein.

“Why is it that no one understands me and everyone likes me?” Einstein wondered. His appeal lay in his supposed incomprehensibility. Charlie Chaplin understood: “They cheer me because they all understand me,” he remarked, accompanying the theoretical physicist to a film premiere, “and they cheer you because no one understands you.”

Several books serve to mark the centenary of the 1919 eclipse observations. Though their aims diverge, they all to some degree capture the likeness of Einstein the man, messy personal life and all, while rendering his physics a little bit more comprehensible to the rest of us. Each successfully negotiates the single besetting difficulty facing books of this sort, namely the way science lends itself to bad history.

Science uses its past as an object lesson, clearing all the human messiness away to leave the ideas standing. History, on the other hand factors in as much human messiness as possible to show how the business of science is as contingent and dramatic as any other human activity.

While dealing with human matters, some ambiguity over causes and effects is welcome. There are two sides to every story, and so on and so forth: any less nuanced approach seems suspiciously moralistic. One need only look at the way various commentators have interpreted Einstein’s relationship with his first wife.

Einstein was, by the end of their failing marriage, notoriously horrible to Mileva Einstein-Maric; this in spite of their great personal and intellectual closeness as first-year physics students at the Federal Swiss Polytechnic. Einstein once reassured Elsa Lowenthal, his cousin and second-wife-to-be, that “I treat my wife as an employee I can not fire.” (Why Elsa, reading that, didn’t run a mile, is not recorded.)

Albert was a bad husband. His wife was a mathematician. Therefore Albert stole his theory of special relativity from Mileva. This shibboleth, bandied about since the 1970s, is a sort of of evil twin of whig history, distorted by teleology, anachronism and present-mindedness. It does no one any favours. The three separately authored parts of Einstein’s Wife: The real story of Mileva Einstein-Maric unpick the myth of Mileva’s influence over Albert, while increasing, rather than diminishing, our interest in and admiration of the woman herself. It’s a hard job to do well, without preciousness or special pleading, especially in today’s resentment-ridden and over-sensitive political climate, and the book is an impressive, compassionate accomplishment.

Matthew Stanley’s Einstein’s War, on the other hand, tips ever so slightly in the other direction, towards the simplistic and the didactic. His intentions, however, are benign — he is here to praise Einstein and Eddington and their fellows, not bury them — and his slightly on-the-nose style is ultimately mandated by the sheer scale of what he is trying to do, for he succeeds in wrapping the global, national and scientific politics of an era up in a compelling story of one man’s wild theory, lucidly sketched, and its experimental confirmation in the unlikeliest and most exotic circumstances.

The world science studies is truly a blooming, buzzing confusion. It is not in the least bit causal, in the ordinary human sense. Far from there being a paucity of good stories in science, there are a limitless number of perfectly valid, perfectly accurate, perfectly true stories, all describing the same phenomenon from different points of view.

Understanding the stories abroad in the physical sciences at the fin de siecle, seeing which ones Einstein adopted, why he adopted them, and why, in some cases, he swapped them for others, certainly doesn’t make his theorising easy. But it does give us a gut sense of why he was so baffled by the public’s response to his work. The moment we are able to put him in the context of co-workers, peers and friends, we see that Einstein was perfecting classical physics, not overthrowing it, and that his supposedly peculiar theory of relativity — as the man said himself –“harmonizes with every possible outlook of philosophy and does not interfere with being an idealist or materialist, pragmatist or whatever else one likes.”

In science, we need simplification. We welcome a didactic account. Choices must be made, and held to. Gravity’s Century by the science writer Ron Cowen is the most condensed of the books mentioned here; it frequently runs right up to the limit of how far complex ideas can be compressed without slipping into unavoidable falsehood. I reckon I spotted a couple of questionable interpretations. But these were so minor as to be hardly more than matters of taste, when set against Cowen’s overall achievement. This is as good a short introduction to Einstein’s thought as one could wish for. It even contrives to discuss confirmatory experiments and observations whose final results were only announced as I was writing this piece.

No Shadow of a Doubt is more ponderous, but for good reason: the author Daniel Kennefick, an astrophysicist and historian of science, is out to defend the astronomer Eddington against criticisms more serious, more detailed, and framed more conscientiously, than any thrown at that cad Einstein.

Eddington was an English pacifist and internationalist who made no bones about wanting his eclipse observations to champion the theories of a German-born physicist, even as jingoism reached its crescendo on both sides of the Great War. Given the sheer bloody difficulty of the observations themselves, and considering the political inflection given them by the man orchestrating the work, are Eddington’s results to be trusted?

Kennefick is adamant that they are, modern naysayers to the contrary, and in conclusion to his always insightful biography, he says something interesting about the way historians, and especially historians of science, tend to underestimate the past. “Scientists regard continuous improvement in measurement as a hallmark of science that is unremarkable except where it is absent,” he observes. “If it is absent, it tells us nothing except that someone involved has behaved in a way that is unscientific or incompetent, or both.” But, Kennefick observes, such improvement is only possible with practice — and eclipses come round too infrequently for practice to make much difference. Contemporary attempts to recreate Eddington’s observations face the exact same challenges Eddington did, and “it seems, as one might expect, that the teams who took and handled the data knew best after all.”

It was Einstein’s peculiar fate that his reputation for intellectual and personal weirdness has concealed the architectural elegance of his work. Higher-order explanations of general relativity have become clichés of science fiction. The way massive bodies bend spacetime like a rubber sheet is an image that saturates elementary science classes, to the point of tedium.

Einstein hated those rubber-sheet metaphors for a different reason. “Since the mathematicians pounced on the relativity theory,” he complained, “I no longer understand it myself.” We play about with thoughts of bouncy sheets. Einstein had to understand their behaviours mathematically in four dimensions (three of space and one of time), crunching equations so radically non-linear, their results would change the value of the numbers originally put into them in feedback loops that drove the man out of his mind. “Never in my life have I tormented myself anything like this,” he moaned.

For the rest of us, however, A little, prophylactic exposure to Einstein’s actual work pays huge dividends. It sweeps some of the weirdness away and reveals Einstein’s actual achievement: theories that set all the forces above the atomic scale dancing with an elegance Isaac Newton, founding father of classical physics, would have half-recognised, and wholly admired.