Reading We Are Electric by Sally Adee for the Times, 28 January 2023

In an attempt to elucidate the role of electricity in biology, German polymath Alexander von Humboldt once stuck a charged wire up his bum and found that “a bright light appears before both eyes”.

Why the study of biological electricity should prove so irremediably smutty — so that serious ”electricians” (as the early researchers called themselves) steered well clear of bodies for well over a century — is a mystery science journalist Sally Adee would rather not have to re-hash, though her by-the-by account of “two hundred years of electro-foolery”, during which quacks peddled any number of cockeyed devices to treat everything from cancer to excessive masturbation, is highly entertaining.

And while this history of electricity’s role in the body begins, conventionally enough, with Volta and Galvani, with spasming frog’s legs and other fairly gruesome experiments, this is really just necessary groundwork, so that Adee can better explain recent findings that are transforming our understanding of how bodies grow and develop, heal and regenerate.

Why bodies turn out the way they do has proved a vexing puzzle for the longest while. Genetics offers no answer, as DNA contains no spatial information. There are genes for, say, eye colour, but no genes for “grow two eyes”, and no genes for “stick two eyes in front of your head”

So if genes don’t tell us the shape we should take as we grow, what does? The clue is in the title: we are, indeed, electric.

Adee explains that the forty trillion or so cells in our bodies are in constant electrical communication with each other. This chatter generates a field that dictates the form we take. For every structure in the body there is a specific membrane voltage range, and our cells specialise to perform different functions in line with the electrical cues they pick up from their neighbours. Which is (by way of arresting illustration) how in 2011 a grad student by the name of Sherry Aw managed, by manipulating electrical fields, to grow eyes on a developing frog’s belly.

The wonder is that this news will come as such a shock to so many readers (including, I dare say, many jobbing scientists). That our cells communicate electrically with each other without the mediation of nerves, and that the nervous system is only one of at least two (and probably many more) electrical communications systems — all this will come as a disconcerting surprise to many. Did you know you only have to put skin, bone, blood, nerve — indeed, any biological cell — into a petri dish and apply an electric field, and you will find all the cells will crawl to the same end of the dish? It’s taken decades before anyone thought to unpick the enormous implications of that fact.

Now we have begun to understand the importance of electrical fields in biology, we can begin to manipulate them. We’ve begun to restore some function after severe spinal injury (in humans) regrown whole limbs (in mice), and even turned cancerous tumours back into healthy tissue (in petri dishes).

Has bio-electricity — once the precinct of quacks and contrarians — at last come into its own? Has it matured? Has it grown up?

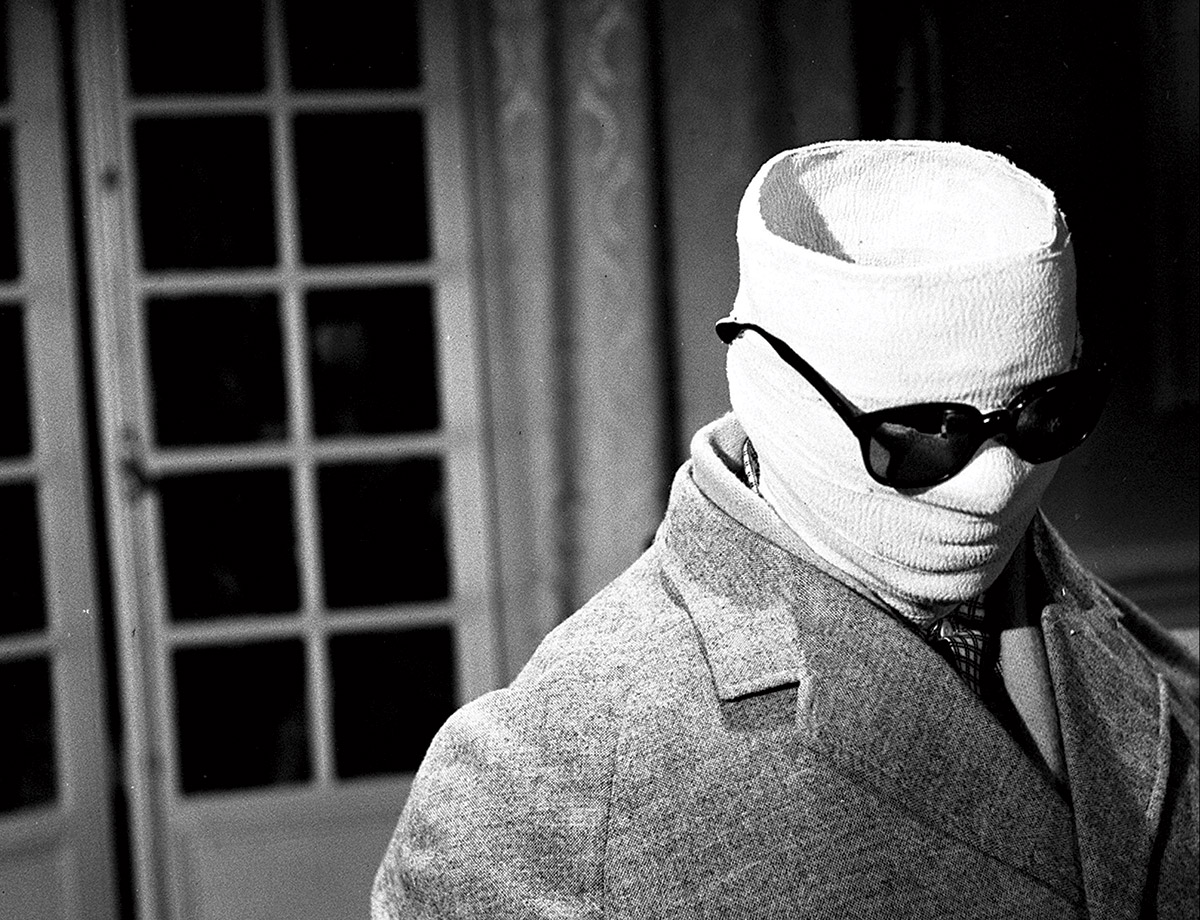

Well, yes and no. Adee would like to deliver a clear, single message about bioelectricity, but the field itself is still massively divided. On the one hand there are ground-breaking researches being conducted into development, regeneration and healing. On the other, there are those who think electricity in the body is mostly to do with nerves and brains, and their project — to hack peoples’ minds through their central nervous systems and usher in some sort of psychoelectric utopia — shows no sign of faltering.

In the 1960s the American neurophysiologist Warren McCulloch worked on the assumption that the way neurons fire is a kind of biological binary code. this led to a new school of thought, called cybernetics — a science of communications and automatic control systems, both living and mechanical. The idea was we should be able to drive an animal like a robot by simply activating specific circuits, an idea “so compelling” says Adee, “there wasn’t much point bothering with whether it was based in fact.”

Very many other researchers Adee writes about are just as wedded to the idea of the body as a meat machine.

This book arose from an article Adee wrote for the magazine New Scientist about her experiences playing DARWARS Ambush!, a military training simulation conducted in a Californian defence lab that (maybe) amped up her response times and (maybe) increased her focus — all by means of a headset that magnetically tickled precise regions in her brain.

Within days of the article’s publication in early 2012, Adee had become a sort of Joan of Arc figure for the online posthumanist community, and even turns up in Noah Yuval Harai’s book, where she serves as an Awful Warning about men becoming gods.

Adee finally admits that she would “love to take this whole idea of the body as an inferior meat puppet to be augmented with metal and absolutely launch it into the sun.” Coming clean at last, she admits she is much more interested in the basic research going on into the communications within and between individual cells — a field where the more we know, the more we realise just how much we don’t understand.

Adee’s enthusiasm is infectious, and she conveys well the jaw-dropping scale and complexity of this newly discovered “electrome”. This is more than medicine. “The real excitement of the field,” she writes, “hews closer to the excitement around cosmology.”