The Wheel: Inventions and reinventions by Richard W. Bulliet (Columbia University Press), for New Scientist, 20 January 2016

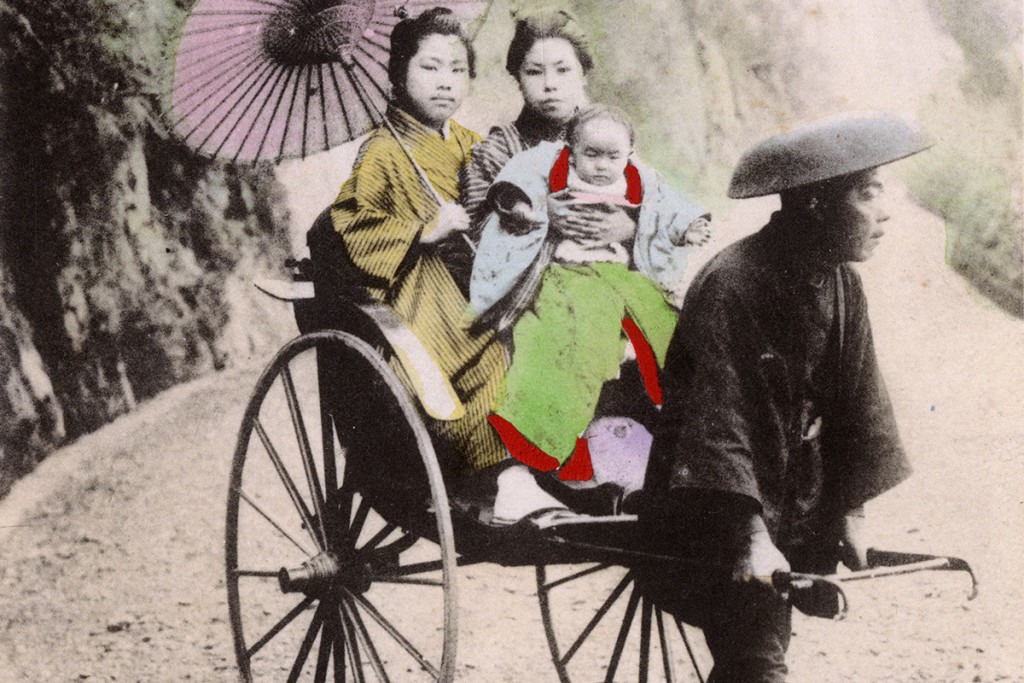

IN 1870, a year after the first rickshaws appeared in Japan, three inventors separately applied for exclusive rights. Already, there were too many workshops serving the burgeoning market.

We will never know which of them, if any, invented this internationally popular, stackable, hand-drawn passenger cart. Just three years after its invention, the rickshaw had totally displaced the palanquin (a covered litter carried on the shoulders of two bearers) as the preferred mode of passenger transport in Japan.

What made the rickshaw so different from a wagon or an ox-cart and, in the eyes of many Westerners, so cruel, was the idea of it being pulled by a man instead of a farm animal. Pushing wheelchairs and baby carriages posed no problem, but pulling turned a man into a beast. “This quirk of perception,” Bulliet says, “reflects a history of human-animal relations that the Japanese – who ate little red meat, had few large herds of cattle and horses, and seldom used animals to pull vehicles – did not share with Westerners.”

In answer to some questions that seem far more difficult, Bulliet provides extraordinarily precise answers. He proposes an exact birth for the wheel: the wheel-set design, whereby wheels are fixed to rotating axles, was invented for use on mine cars in copper mines in the Carpathian mountains, perhaps as early as 4000 BC.

Other questions remain intractable. Why did wheeled vehicles not catch on in pre-Columbian America? The peoples of North and South America did not use wheels for transportation before Christopher Columbus arrived. They made wheeled toys, though. Cattle-herding societies from Senegal to Kenya were not taken in by wheels either, though they were happy enough to feature the chariots of visitors in their rock paintings.

Bulliet has a lot of fun teasing generations of anthropologists, archaeologists and historians for whom the wheel has been a symbol of self-evident utility: how could those foreign types not get it? His answer is radical: the wheel is actually not that great an idea. It only really came into its own once John McAdam, a Scot born in 1756, introduced a superior way to build roads. It’s worth remembering that McAdam insisted the best way to manufacture the small, sharp-edged stones he needed was to have workers, including women and children, sit beside the road and break up larger rocks. So much for progress.

The wheel revolution is, to Bulliet’s mind, a recent and largely human-powered one. Bicycles, shopping carts, baby strollers, dollies, gurneys and roll-aboard luggage: none of these was conceived before 1800. At the dawn of Europe’s Renaissance, in the 14th century, four-wheeled vehicles were not in common use anywhere in the world.

Bulliet ends his history with the oddly conventional observation that “invention is seldom a simple matter of who thought of something first”. He could have challenged the modern shibboleth (born in Samuel Butler’s Erewhon and given mature expression in George Dyson’s Darwin Among the Machines) that technology evolves. Add energy to an unbounded system, and complexity is pretty much inevitable. There is nothing inevitable about technology, though; human agency cannot be ignored. Even a technology as ubiquitous as the wheel turns out to be a scrappy hostage to historical contingency.

I may be misrepresenting the author’s argument here. It is hard to tell, because Bulliet approaches the philosophy of technology quite gingerly. He can afford to release the soft pedal. This is a fascinating book, but we need more, Professor Bulliet!