In 2013 the world’s news media, fell in love with Talea, a Mexican pueblo (population 2400) in Rincón, a remote corner of Northern Oaxaca. América Móvil, the telecommunications giant that ostensibly served their area, had refused to provide them with a mobile phone service, so the plucky Taleans had built a network of their own.

Imagine it: a bunch of indigenous maize growers, subsistence farmers with little formal education, besting and embarrassing Carlos Slim, América Móvil’s owner and, according to Forbes magazine at the time, the richest person in the world!

The full story of that short-lived, homegrown network is more complicated, says Roberto González in his fascinating, if somewhat self-conscious account of rural innovation.

Talea was never a backwater. A community that survives Spanish conquest and resists 500 years of interference by centralised government may become many things, but “backward” is not one of them.

On the other hand, Gonzalez harbours no illusions about how communities, however sophisticated, might resist the pall of globalising capital — or why they would even want to. That homogenising whirlwind of technology, finance and bureaucracy also brings with it roads, hospitals, schools, entertainment, jobs, and medicine that actually works.

For every outside opportunity seized, however, an indigenous skill must be forgotten. Talea’s farmers can now export coffee and other cash crops, but many fields lie abandoned, as the town’s youth migrate to the United States. The village still tries to run its own affairs — indeed, the entire Oaxaca region staged an uprising against centralised Mexican authority in 2006. But the movement’s brutal repression by the state augurs ill for the region’s autonomy. And if you’ve no head for history, well, just look around. Pueblos are traditionally made of mud. It’s a much easier, cheaper, more repairable and more ecologically sensitive material than the imported alternatives. Still, almost every new building here is made of concrete.

In 2012, Talea gave its backing to another piece of imported modernity — a do-it-yourself phone network, assembled by Peter Bloom, a US-born rural development specialist, and Erick Huerta, a Mexican telecommunications lawyer. Both considered access to mobile phone networks and the internet to be a human right.

Also helping — and giving the lie to the idea that the network was somehow a homegrown idea — were “Kino”, a hacker who helped indigenous communities evade state controls, and Minerva Cuevas, a Mexican artist best known for hacking supermarket bar codes.

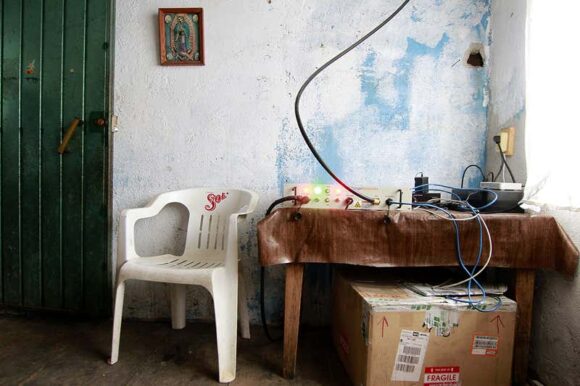

By 2012 Talea’s telephone network was running off an open-source mobile phone network program called OpenBTS (BTS stands for base transceiver station). Mobiles within range of a base station can communicate with each other, and connect globally over the internet using VoIP (or Voice over Internet Protocol). All the network needed was an electrical power socket and an internet connection — utilities Talea had enjoyed for years.

The network never worked very well. Whenever the internet went down, which it did occasionally, the whole town lost its mobile coverage. Recently the phone company Movistar has moved in with an aggressive plan to provide the region with regular (if costly) commercial coverage. Talea’s autonomous network idea lives on, however, in a cooperative organization of community cell phone networks which today represents nearly seventy pueblos across several different regions in Oaxaca.

Connected is an unsentimental account of how a rural community takes control (even if only for a little while) over the very forces that threaten its cultural existence. Talea’s people are dispersing ever more quickly across continents and platforms in search of a better life. The “virtual Taleas” they create on Facebook and other sites to remember their origins are touching, but the fact remains: 50 years of development have done more to unravel a local culture than 500 years of conquest.