Watching Son of Monarchs for New Scientist, 3 November 2021

“This is you!” says Bob, Mendel’s boss at a genetics laboratory in New York City. He holds the journal out for his young colleague to see: on its cover there’s a close-up of the wing of a monarch butterfly. The cover-line announces the lab’s achievement: they have shown how the evolution and development of butterfly color and iridescence are controlled by a single master regulatory gene.

Bob (William Mapother) sees something is wrong. Softer now: “This is you. Own it.”

But Mendel, Bob’s talented Mexican post-doc (played by Tenoch Huerta, familiar from the Netflix series Narcos: Mexico), is near to tears.

Something has gone badly wrong in Mendel’s life. And he’s no more comfortable back home, in the butterfly forests of Michoacán, than he was in Manhattan. In some ways things are worse. Even at their grandmother’s funeral, his brother Simon (Noé Hernández) won’t give him an inch. At least the lab was friendly.

Bit by bit, through touching flashbacks, some disposable dream sequences and one rather overwrought row, we learn the story: how, when Mendel and Simon were children, a mining accident drowned their parents; how their grandmother took them in, but things were never the same; how Simon went to work for the predatory company responsible for the accident, and has ever since felt judged by his high-flying, science-whizz, citizen-of-nowhere brother.

When Son of Monarchs premiered at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, critics picked up on its themes of borders and belonging, the harm walls do and all the ways nature undermines them. Mendel grew up in a forest alive with clouds of Monarch butterflies. (In the film the area, a national reserve, is threatened by mining; these days, tourism is arguably the bigger threat.) Sarah, Mendel’s New York girlfriend (Alexia Rasmussen; note-perfect but somewhat under-used) is an amateur trapeze artist. The point — that airborn creatures know no frontiers — is clear enough; just in case you missed it, a flashback shows young Mendel and young Simon in happier days, discussing humanity’s airborne future.

In a strongly scripted film, such gestures would have been painfully heavy-handed. Here, though, they’re pretty much all the viewer has to go on in this sometimes painfully indirect film.

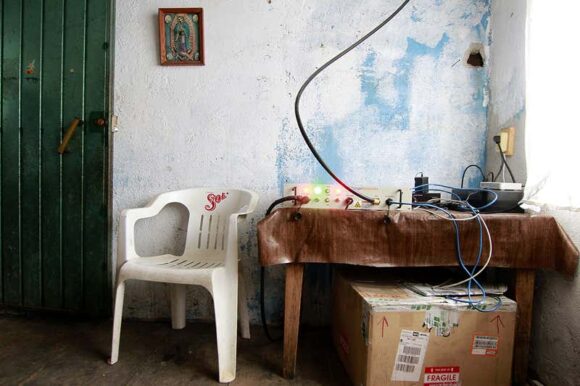

The plot does come together, though, through the character of Mendel’s old friend Vicente (a stand-out performance by the relative unknown Gabino Rodríguez). While muddling along like everyone else in the village of Angangueo (the real-life site, in 2010, of some horrific mine-related mudslides), Vicente has been developing peculiar animistic rituals. His unique brand of masked howling seems jolly silly at first glance — just a backwoodsman’s high spirits — but as the film advances, we realise that these rituals are just what Mendel needs.

For a man trapped between worlds, Vicente’s rituals offer a genuine way out: a way to re-engage imaginatively with the living world.

So, yes, Son of Monarchs is, on one level, about identity, about how a cosmopolitan high-flier learns to be a good son of Angangeo. But more than that, it’s about personality: about how Mendel learns to live both as a scientist, and as a man lost among butterflies.

French-Venezuelan filmmaker Alexis Gambis is himself a biologist and founded the Imagine Science Film Festival. While Son of Monarchs is steeped in colour, and full of cinematographer Alejandro Mejía’s mouth-watering (occasionally stomach-churning) macro-photography of butterflies and their pupae, ultimately this is a film, not about the findings of science, but about science as a vocation.

Gambis’s previous feature, The Fly Room (2014) was about the inspiration a 10-year-old girl draws from visits to T H Morgan’s famous (and famously cramped) “Fly Room” drosophila laboratory. Son of Monarchs asks what can be done if inspiration dries up. It is a hopeful film and, on more than the visual level, a beautiful one.