In November 2020, the International Council of Museums estimated that 6.1 per cent of museums globally were resigned to permanent closure due to the pandemic. The figure was welcomed with enthusiasm: in May, it had reported nearly 13 per cent faced demise.

Something is changing for the better. This isn’t a story about how galleries and museums have used technology to save themselves during lockdowns (many didn’t try; many couldn’t afford to try; many tried and failed). But it is a story of how they weathered lockdowns and ongoing restrictions by using tech to future-proof themselves.

One key tool turned out to be virtual tours. Before 2020, they were under-resourced novelties; quickly, they became one of the few ways for galleries and museums to engage with the public. The best is arguably one through the Tomb of Pharaoh Ramses VI, by the Egyptian Tourism Authority and Cairo-based studio VRTEEK.

And while interfaces remain clunky, they improved throughout the year, as exhibition-goers can see in the 360-degree virtual tour created by the Museum of Fine Arts Ghent in Belgium to draw people through its otherwise-mothballed Van Eyck exhibition.

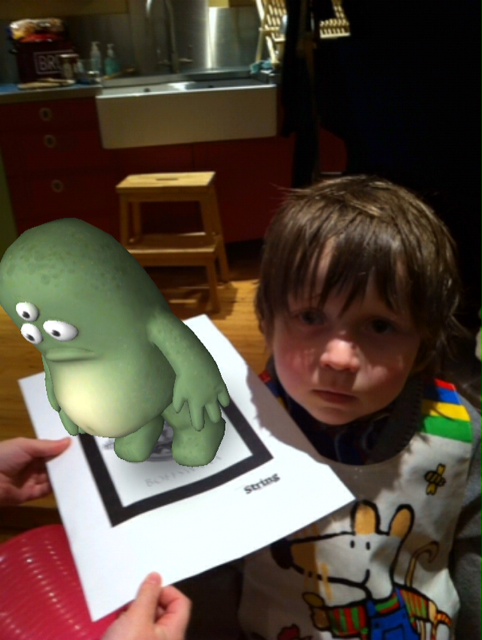

The past year has also forced the hands of curators, pushing them into uncharted territory where the distinctions between the real and the virtual become progressively more ambiguous.

With uncanny timing, the V&A in London had chosen Lewis Carroll’s Alice books for its 2020 summer show. Forced into the virtual realm by covid-19 restrictions, the V&A, working with HTC Vive Arts, created a VR game based in Wonderland, where people can follow their own White Rabbit, solve the caterpillar’s mind-bending riddles, visit the Queen of Hearts’ croquet garden and more. Curious Alice is available through Viveport; the real-world show is slated to open on 27 March.

Will museums grow their online experiences into commercial offerings? Almost all such tours are free at the moment, or are used to build community. If this format is really going to make an impact, it will probably have to develop a consolidated subscription service – a sort of arts Netflix or Spotify.

What the price point should be is anyone’s guess. It doesn’t help for institutions to muddy the waters by calling their video tours virtual tours.

But the advantages are obvious. The crowded conditions in galleries and museums have been miserable for years – witness the Mona Lisa, imprisoned behind bulletproof glass under low-level diffuse lighting and protected by barricades. Art isn’t “available” in any real sense when you can only spend 10 seconds with a piece. I can’t be alone in having staggered out of some exhibitions with no clear idea of what I had seen or why. Imagine if that was your first experience of fine art.

Why do we go to museums and galleries expecting to see originals? The Victorians didn’t. They knew the value of copies and reproductions. In the US in particular, museums lacked “real” antiquities, and plaster casts were highly valued. The casts aren’t indistinguishable from the original, but what if we produced copies that were exact in information as well as appearance? As British art critic Jonathan Jones says: “This is not a new age of fakery. It’s a new era of knowledge.”

With lidar, photogrammetry and new printing techniques, great statues, frescoes and chapels can be recreated anywhere. This promises to spread the crowds and give local museums and galleries a new lease of life. At last, they can become places where we think about art – not merely gawp at it.