Contemplating nimiia cétiï for New Scientist, 11 September 2018

The artist Jenna Sutela normally divides her time between London and Helsinki, but she has spent the last four months at London’s Somerset House Studios, thanks to a residency with Google Arts & Culture. Here, she’s been either making a video, learning about computers, teaching artificial intelligences to dream, or mastering Martian. Perhaps all of the above. It depends who you speak to.

The artists Google invites to explore the potentials of its machine learning systems normally wind up in its lab in Paris. This time, however, Google engineer Damien Henry (the co-inventor, incidentally of the Google Cardboard VR headset) has been travelling to London to assist Sutela and her artistic mentor, the Turkish-born data artist Memo Akten, in a project that, the more you learn about it, resembles an alchemical operation more than a work of art.

Here – so far as I understand it – is the recipe.

- Take one nineteenth-century French medium, Hélène Smith, who made much of her communications with Martians. (The Surrealists lapped this stuff up: they dubbed her “the muse of automatic writing”.) Make up some phonemes to match her Martian lettering. Speak Martian.

- Prepare a dish of Bacillus subtilis, a bacterium that we expect would cope rather well with conditions on Mars. Point a camera at it, and direct the video signal through a machine learning system. (Don’t call this an AI, whatever you do. Atkin has issued a public warning that “every time someone personifies this stuff, every time someone talks about ‘the AI’, a kitten is strangled.”)

- Lie to your AI. Tell it that your dish of wiggling bacteria is in fact a musical score. Record the music your AI makes as it tries to read the dish. Hide kittens.

- Keep lying. Tell it your dish of wiggling bacteria is a text.

- – a language.

- – a map.

- Write down the text. Speak the language. Read the map. Put the whole enterprise into a single twelve-minute video and hang it up in the foyer of London’s Somerset House Studios.

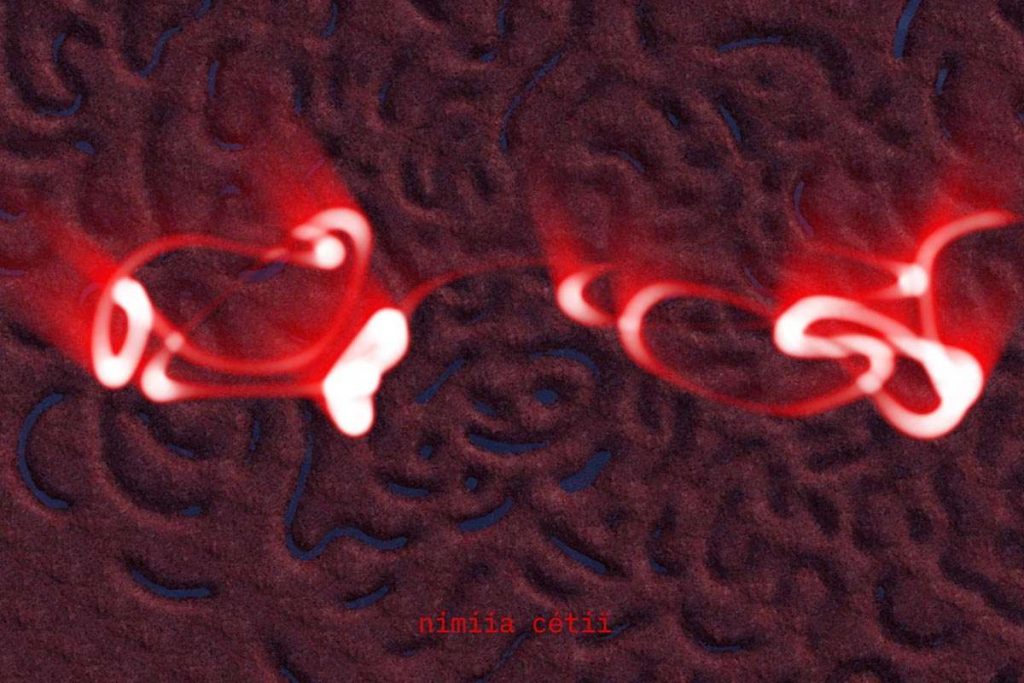

Titled nimiia cétiï and on view in Somerset House Studios until 15 September, Sutela’s video installation is heavy-going at first, but well worth some close scrutiny. Everything you see and hear came from that petri dish: the landscape, the music, the alien script, even its eerily convincing Martian vocalisation. “There is,” Henry tells me with avuncular pride, “absolutely no scientific goal to this project whatsoever.”

The point being that Sutela is one of the first artists, if not the first, to appropriate the rules of machine learning entirely to her own ends. It’s a milestone of sorts. She’s not illustrating an idea, or demonstrating some technical capability. She’s using machine learning like a brush, to conjure up imaginary worlds.

Which is to take nothing away from nimiia cétiï‘s considerable technical achievement. Sutela is forcing her recurrent neural network to over-interpret its little petri dish-shaped world. We’re a long way from inventing a machine that sees pictures in a fire, but these results are certainly suggestive.

«e tesi leca rizini nirnemea riechee sat ze po mizi» as a Martian might say.