Reading Remnants of Ancient Life by Dale Greenwalt for New Scientist, 11 January 2023

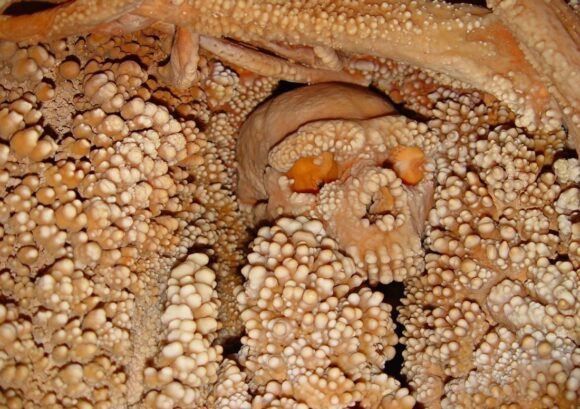

What is a fossil made of? Mineralised rocky fossils are what spring to mind at a first mention of the word, but the preserved fauna of the burgess shale are pure carbon, a kind of proto-coal. Then there are those tantalising cretaceous insects preserved in amber.

Whatever they are made of, fossils contain treasures. The first really good microscopic study of (mineralised) dinosaur bone, revealing its internal structure, was written up in 1850 by the British palaeontologist Gideon Mantell.

Still, classifying fossil organisms on the basis of their shape and their location seemed to be virtually the only weapon in the paleobiologist’s arsenal — until 1993. That was the year Michael Crichton’s novel Jurassic Park famously captured the excitement of a field in turmoil, as ancient pigments, proteins, and DNA were being detected (not too reliably at first) in all manner of fossil substrates, including rock.

Jurassic Park’s blood-sucking insects fossilised in amber were a bust. Though seemingly perfectly preserved on the outside, they turned out to be hollow.

Mind you, the author of Remnants (a dull title for this vivid and gripping book) has himself has managed to get traces of ancient haemoglobin out of the bloated stomach of a fossilised mosquito — so never say die.

Greenwalt, who spends eleven months of every year “buried deep in the bowels of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History in Washington, DC,” has brought to the surface a riveting account of a field achieving insights quite as revolutionary as any conjectured by Crichton. The finds are extraordinary enough: a cholesterol-like molecule in a 380-million-year-old crustacean; chitin from the exoskeleton of a fossil from the 505-million-year-old burgess shale. Even more extraordinary are the inferences we can then draw about the physiology, behaviour, and evolution of these extinct organisms. Even from traces that are smeared, fragmented, degraded, and condensed, even from cyclized and polymerized materials, valuable insights can be drawn. It is even possible to calculate and construct putative “ancestral proteins” and from their study, conclude that Earth’s life had its origins at the mouths of deep ocean vents!

The story of biomolecules in palaeontology has its salutary side. A generation of brilliant innovators have had to calm down, learn the limitations of their new techniques, and return, as often as not, to the insights of comparative anatomy to confirm and calibrate their work. Polymerase-chain-reaction sequencing (PCR) is the engine powering our ever older and ever more complete ancient DNA sequences, but early teething problems included publication of a DNA sequence thought to be from a 120-million-year-old weevil that actually belonged to a fungus. Technologies prove their worth over time.

More problematic are the cul-de-sacs. In 2007 Greenwalt’s colleague, the palaeontologist Mary Schweitzer reported her lab had recovered short sequences of collagen from the femur of a 68-million-year-old Tyrannosaurus rex. As Matthew Collins at the University of Copenhagen complains, “It’s great work. I just can’t replicate it.” Schweitzer’s methodology has survived 15 years’ hard interrogation, it may simply be that animal proteins cannot survive more than about 4 million years. That still makes them much hardier than plant proteins, which only last for about 30,000 years.

Against these fascinating controversies and surprising dead-ends Greenwalt sets many wonders, not least “the seemingly unlimited potential of ancient DNA to shed light on the ancestry of our species, Homo sapiens”. And for short-changed botanists, there’s an extraordinary twist in Greenwalt’s tale whereby it may become possible to classify plants based, not on their morphology or even their DNA, but on the repertoire of small biomolecules they leave behind. “The biomolecular components of plants have been found as biomarkers in rocks that are two and a half billion — with a ‘b’!—years old,” Greenwalt exclaims (p204). The 3.7-billion-year-old cyano-bacteria that produced stromatolites in Greenland are the same age as the rocks at Mars’s Gale Crater: “Are authentic ancient biomolecules on Mars so implausible?” Greenwalt asks.

His day job may keep him for months at a time in the Smithsonian’s basement, but Greenwalt’s gaze is set firmly on the stars.