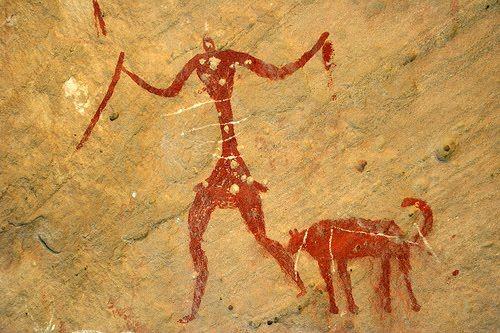

Sometimes, when Spanish and other European forces entered lands occupied by the indigenous peoples of South America, they used dogs to massacre the indigenous human population. Occasionally their mastiffs, trained to chase and kill, actually fed upon the bodies of their victims.

The locals’ response was, to say the least, surprising: they fell in love. These beasts were marvellous novelties, loyal and intelligent, and a trade in domesticated dogs spread across a harrowed continent.

What is it about the dog, that makes it so irresistible?

Anthropologist Pat Shipman is out to describe the earliest chapters in our species’ relationship with dogs. From a welter of archaeological and paleo-genetic detail, Shipman has fashioned an unnerving little epic of love and loyalty, hunting and killing.

There was, in Shipman’s account, nothing inevitable, nothing destined, about the relationship that turned the grey wolf into a dog. Yes, early Homo sapiens hunted with early “wolf-dogs” in a symbiotic relationship that let humans borrow a wolf’s superior speed and senses, while allowing wolves to share in a human’s magical ability to kill prey at a distance with spears or arrows. But why, in the pursuit of more food, would humans take in, feed, nurture, and breed another meat-eating animal? Shipman puts it more forcefully: “Who would select such a ferocious and formidable predator as a wolf for an ally and companion?”

To find the answer, says Shipman, forget intentionality. Forget the old tale in which someone captures a baby animal, tames it, raises it, selects a mate for it, and brings up the friendliest babies.

Instead, it was the particular ecology of Europe about 50,000 years ago that drove grey wolves and human interlopers from Mesopotamia into close cooperation, thereby seeing off most large game and Europe’s own indigenous Neanderthals.

This story was explored in Shipman’s 2015 The Invaders. Our Oldest Companions develops that argument to explain why dogs and humans did not co-evolve similar behaviours elsewhere.

Australia provides Shipman with her most striking example. Homo sapiens first arrived in Australia without dogs, because back then (around 35,000 years ago, possibly earlier) there were no such things. (The first undisputed dog remains belong to the Bonn-Oberkassel dog, buried beside humans 14,200 years ago.)

The ancestors of today’s dingoes were brought to Australia by ship only around 3000 years ago, where their behaviour and charisma immediately earned them a central place in Native Australian folklore.

Yet, in a land very different to Europe, less densely populated by large animals and boasting only two large-sized mammalian predators, the Tasmanian tiger and the marsupial lion (both now extinct), there was never any mutual advantage to be had in dingoes and humans working, hunting, feasting and camping together. Consequently dingoes, though they’re eminently tameable, remain undomesticated.

The story of humans and dogs in Asia remains somewhat unclear, and some researchers still argue that the bond between wolf and man was first established here. Shipman, who’s having none of it, points to a crucial piece of non-evidence: if dogs first arose in Asia, then where are the ancient dog burials?

“Deliberate burial,” Shipman writes, “is just about the gold standard in terms of evidence that an animal was domesticated.” There are no such ancient graves in Asia. It’s near Bonn, on the right bank of the Rhine, that the earliest remains of a clearly domesticated dog were discovered in 1914, tucked between two human skeletons, their grave decorated with works of art made of bones and antlers.

Domesticated dogs now comprise more than 300 subspecies, though overbreeding has left hardly any that are capable of carrying out their intended functions of hunting, guarding, or herding.

Shipman passes no comment, but I can’t help but think this a sad and trivial end to a story that began so heroically, among mammoth and tiger and lion.