Reading Troubled By Faith by Owen Davies, 22 November 2023

Readers of this magazine may recall how, in early 2020, 5G mobile technology got caught up in a conspiracy theory that saw cellphone towers being set on fire across Europe. But how many of us knew just how dated this delusional belief really was?

A medical note from 1889 reports on the plight of one Henry Staples, 59, who ”fancies telegraph wires are over his head” and “that messages are being sent to people as to his character”. A year later, 56-year-old Janet Sneddon from Glasgow presented with an imaginary wire “connecting her to the post office”.

Owen Davies is an historian of magic. Troubled by Faith is his account of how early clinicians met with, understood, and dealt with irrational belief.

In a book that never lets the big ideas get in the way of the always entertaining fine detail, he builds a cast-iron defence of the movement that saw asylums springing up across western Europe in the 1830s. There were certainly abuses — there still are — but asylums were also places of compassion and sensitivity. Nor, by the way, were you ever just dumped there. Half of all “incarcerated” patients left after less than a year, and most within two years.

19th-century asylum records have serious limitations — the patients’ own words are rarely recorded directly — but Davies’s examination reveals what he calls “an extraordinary cultural space where under one roof prophets, messiahs, the bewitched, and the haunted, wrestled with angels, devils, imps, and witches.”

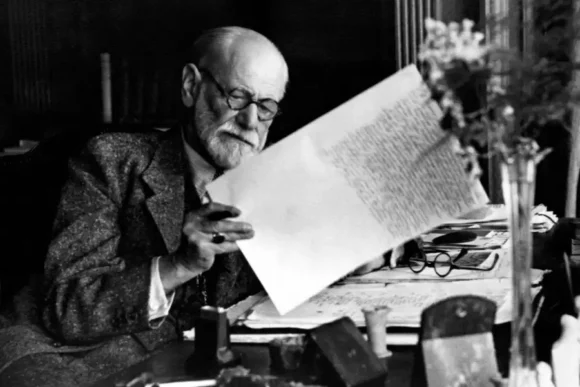

Troubled by Faith is a complex, sometimes tragic and ultimately uplifting story of how intelligence, sympathy and good-will triumphed over clinical ignorance. Growing up imbued with the values of the Enlightenment, doctors like the pioneering French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot and his pupil Sigmund Freud believed that magic was “a diseased survival of a benighted mediaeval past”, and that “madness” was therefore largely determined by history. Ignorance had spread superstition; superstition had fertilised irrational beliefs; and irrational beliefs were driving people into manias and insanias of one sort or another. If you could educate people into thinking rationally, mental wellbeing was bound to follow.

But irrational beliefs were not irreconcilable with modernity after all, Owens explains. Magical thinking, which ruins lives, is just a species of rule-of-thumb thinking, without which day-to-day life is impossible.

These have been humbling lessons for a discipline that, when it started, imagined the problems and mysteries it confronted could be cleared up in a generation.

Troubled by Faith is hardly the first book to be written about the very early years of psychology. But while most of these tend to plash about in the shallows of developing theory, Owens does everyone a tremendous favour by rolling up his sleeves and diving into the lived experiences of distressed and delusional people.

Owens explains how insanity diagnoses spread from behaviour to belief — in witches or fairies or ghosts, in divine or infernal visitations, or in new technologies operating in supernatural ways — and he explains how, by listening to and caring for patients, this diagnostic overreach was eventually corrected.

Many a contemporary observer found such a muddle infuriating, of course. In a long section about the legal culture around insanity, we meet the judge Baron George Bramwell who, we are told, “became something of a bogey figure in the psychiatric community as he routinely critiqued and dismissed medical expert witnesses and scoffed at the notion of moral insanity.”

With hindsight, and thanks to works as insightful as this one, we can afford to be more admiring of the effort to understand the mind, that enjoys reason, but does not need reason to be right.