Reading The Best Minds: A story of friendship, madness and the tragedy of good intentions by Jonathan Rosen. For the Telegraph, 3 April 2023

This is the story of the author’s lifelong friendship with Michael Laudor: his neighbour growing up in in 1970s Westchester County; his rival at Yale; and his role-model as he abandoned a lucrative job for a life of literary struggle. Through what followed — debilitating schizophrenia; law school; and national celebrity as he publicised the plight of people living with mental illness — Laudor became something of a hero for Jonathan Rosen. And in June 1998, in the grip of yet another psychotic episode, he stabbed his pregnant girlfriend to death.

Her name was Caroline Costello and, says Rosen, she would not have been the first person to ascribe everything in Laudor’s disintegration, “from surface tremors to elliptical apocalyptic utterances, to the hidden depths of a complex soul.”

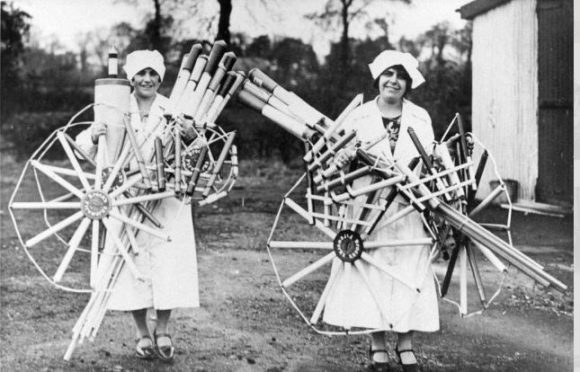

It will take Rosen over 500 pages to unpick Costello and Laudor’s tragedy, but he starts (and so, then, will we) with the Beats — that generation of writers who, he says, “released madness like a fox at a hunt, then rushed after — not to help or heal but to see where it led, and to feel more alive while the chase was on.”

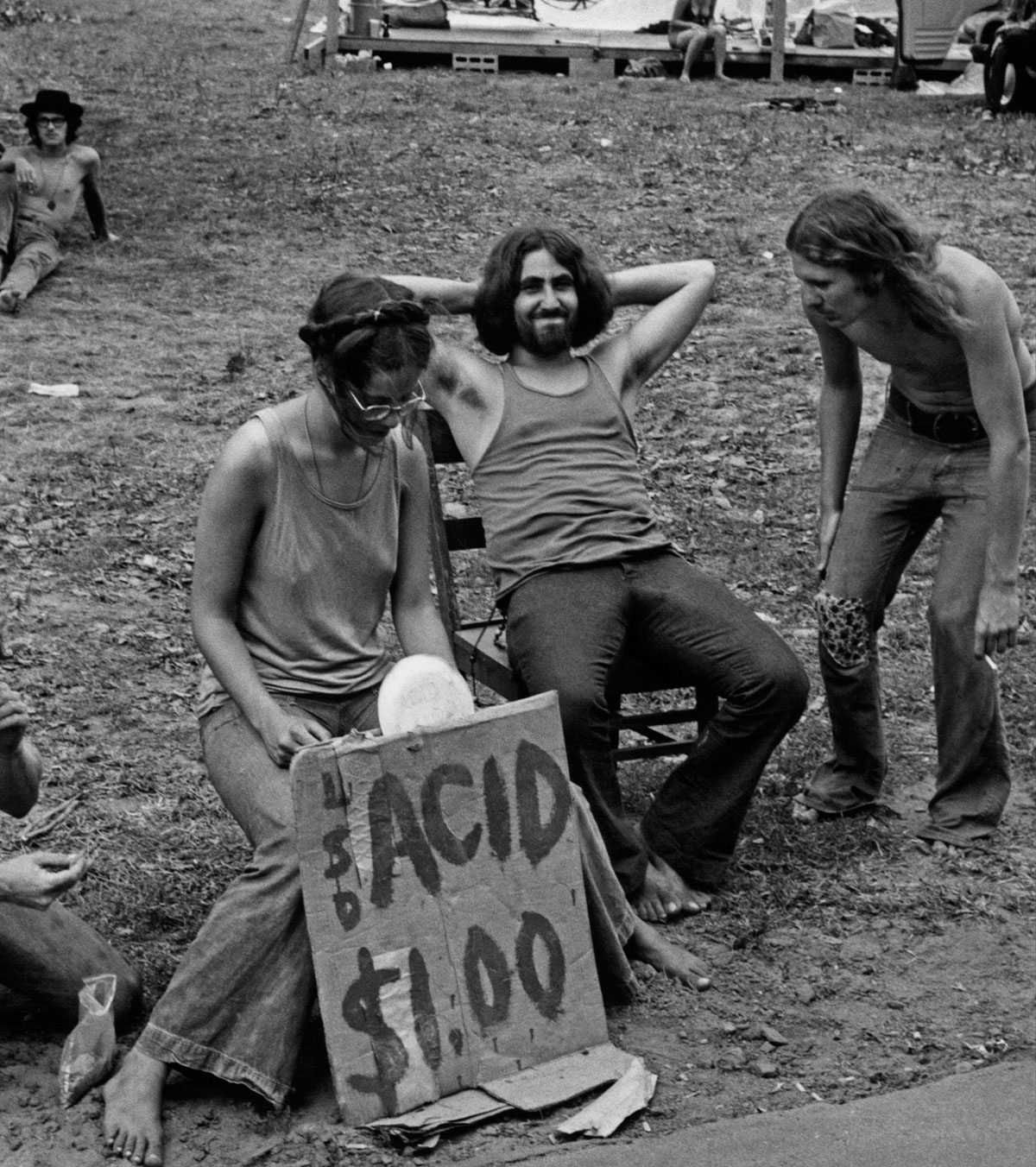

As a young man, the poet Alan Ginsburg (whose Beat poem “Howl” gives this book its title) gave permission for his mother’s lobotomy. He spent the rest of his life atoning for this, “spinning the culture around him,” says Rosen, “into alignment with his mother’s psychosis”. By the summer of 1968 the Esalen Institute in Big Sur was sponsoring events under the heading “The Value of Psychotic Experience”.

To the amateur dramatics of the Beat generation (who declared mental illness a myth) add the hypocrisies of neo-Marxist critics like Paul de Mann (who proved texts mean whatever we want them to mean) and Franz Fanon (for whom violence was a cleansing force with a healing property) and the half-truths of anti-psychiatrists like Felix Guattari, who hid his clinic’s use of ECT to bolster his theory that schizophrenia was a disease of capitalist culture. Stir in the naiveties of the community health movement (that judged all asylums prisons), and policies ushered in by Jack Kennedy’s Community Mental Health Act of 1963 (“predicated,” says Rosen, “on the promise of cures that did not exist, preventions that remained elusive, and treatments that only work for those who were able to comply”); and you will begin to understand the sheer enormity of the doom awaiting Laudor and those he loved, once the 1980s had “backed up an SUV” over the ruins of America’s mental health provision.

This is a tragedy that enters wearing the motley of farce: on leaving Yale, Laudor became a management consultant, hired by the multinational firm Bain & Co. Rosen reckons Laudor got the job by talking with authority even when he didn’t know what he was talking about; “That, in fact, was why they had hired him.”

By the time Laudor enters Yale Law School, however, his progressive disintegration is clear enough to the reader (if not to the Dean of the school, Guido Calabresi, besotted with the way an understanding of mental health could, in Rosen’s words, “undermine the authority of courts, laws, facts, and judges, by exposing the irrational nature of the human mind”).

Soon Michael is being offered a million dollars for his memoir and another million for the movie rights. He’s the poster child for every American living with mental illness, and at the same time, he’s an all-American success story: proof that the human spirit can win out over psychiatric neglect.

Only it didn’t.

No one knows what to do about schizophrenia. The treatments don’t work, except sometimes they do, and when they do, no-one can really say why.

Rosen’s book is a devastating attack on a generation that refused to look this hard truth in the eye, and turned it, instead into some sort of flattering sociopolitical metaphor, and in so doing, deprived desperate people of care.

Rosen’s book is the mea culpa of a man who now understands that “the revolution in consciousness I hoped would free my mind… came at the expense of people whose mental pain I could not begin to fathom.”

It’s the darkest of literary triumphs, and the most gripping of unbearable reads.