Watching John Was Trying to Contact Aliens for New Scientist, 27 August 2020

You have to admire Netflix’s ambition. As well as producing Oscar-winning short documentaries of its own (The White Helmets won in 2017; Period. End of Sentence. won in 2019), the streaming giant makes a regular effort to bring festival-winning factual films to a global audience.

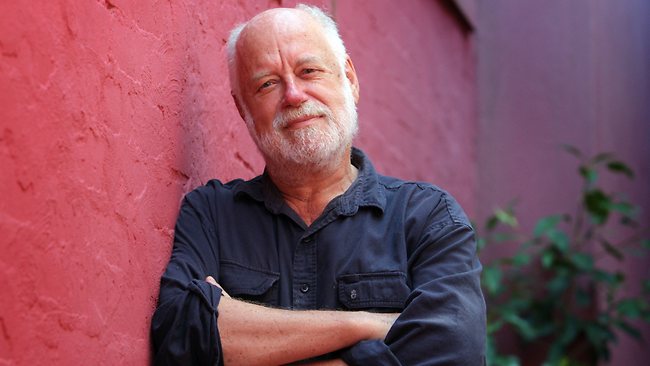

The latest is John Was Trying to Contact Aliens by New York-based UK director Matthew Killip, which won the Jury Award for a non-fiction short film at this year’s Sundance festival in Utah. In little over 15 minutes, it manages to turn the story of John Shepherd, an eccentric inventor who spent 30 years trying to contact extraterrestrials by broadcasting music millions of kilometres into space, into a tear-jerker of epic (indeed, cosmological) proportions.

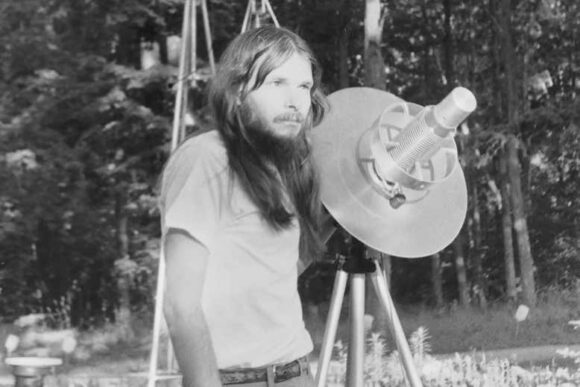

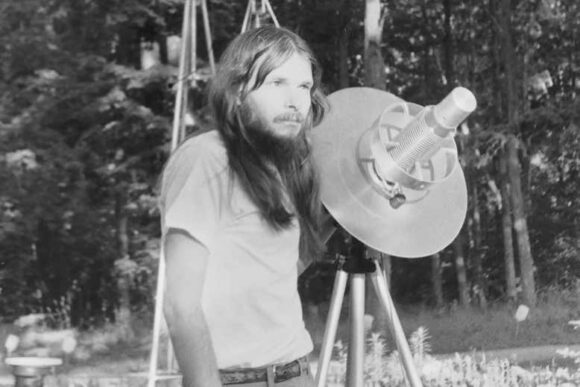

Never much cared for by his parents, Shepherd was brought up by adoptive grandparents in rural Michigan. A fan of classic science-fiction shows like The Outer Limits and The Twilight Zone, Shepherd never could shake off the impression that a UFO sighting made on him as a child, and in 1972 the 21-year-old set about designing and constructing electronic equipment to launch a private search for extraterrestrial intelligence. His first set-up, built around an ultra-low frequency radio transmitter, soon expanded to fill over 100 square metres of his long-suffering grandparents’ home. It also acquired an acronym: Project STRAT – Special Telemetry Research And Tracking.

A two-storey high, 1000-watt, 60,000-volt, deep-space radio transmitter required a house extension – and all so Shepherd could beam jazz, reggae, Afro-pop and German electronica into the sky for hours every day, in the hope any passing aliens would be intrigued enough to come calling.

It would have been the easiest thing in the world for Killip to play up Shepherd’s eccentricity. Until now, Shepherd has been a folk hero in UFO-hunting circles. His photo portrait, surrounded by bizarre broadcasting kit of his own design, appears in Douglas Curren’s In Advance of the Landing: Folk concepts of outer space – the book TV producer Chris Carter says he raided for the first six episodes of his series The X-Files.

Instead, Killip listens closely to Shepherd, discovers the romance, courage and loneliness of his life, and shapes it into a paean to our ability to out-imagine our circumstances and overreach our abilities. There is something heartbreakingly sad, as well as inspiring, about the way Killip pairs Shepherd’s lonely travails in snow-bound Michigan with footage, assembled by teams of who knows how many hundreds, from the archives of NASA.

Shepherd ran out of money for his project in 1998, and having failed to make a connection with ET, quickly found a life-changing connection much closer to home.

I won’t spoil the moment, but I can’t help but notice that, as a film-maker, Killip likes these sorts of structures. In one of his earlier works, The Lichenologist, about Kerry Knudsen, curator of lichens at the University of California, Riverside, Knudsen spends most of the movie staring at very small things before we are treated to the money shot: Knudsen perched on top of a mountain, whipped by the wind and explaining how his youthful psychedelic experiences inspired a lifetime of intense visual study. It is a shot that changes the meaning of the whole film.