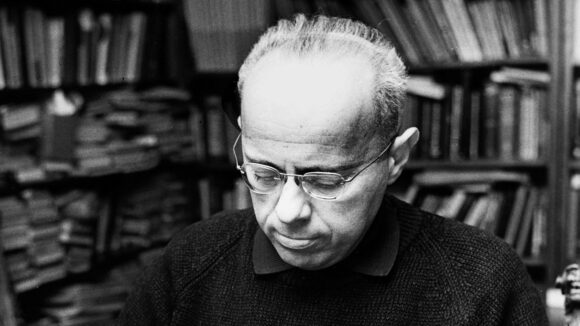

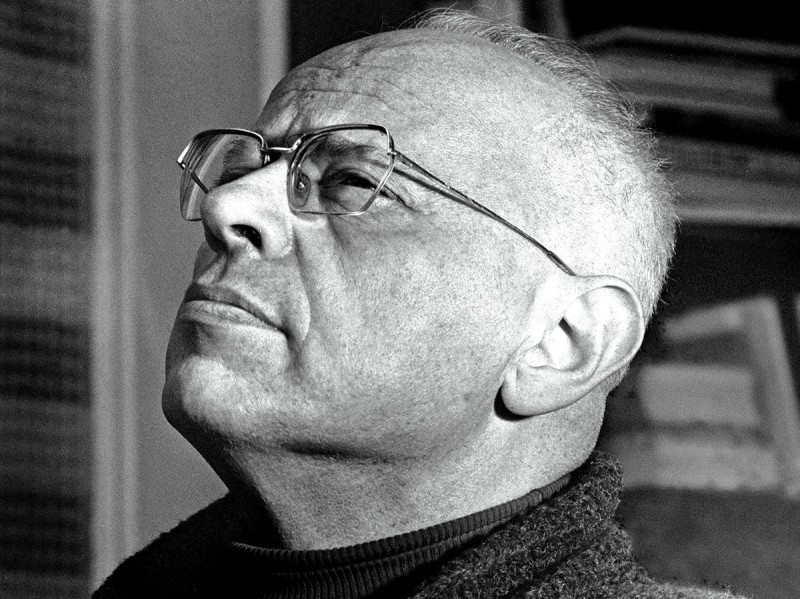

Here’s my foreword to the new MIT edition of Stanislaw Lem’s Return from the Stars.

For a while I lived on the penthouse level of a gherkin-shaped glass tower, five minutes from DIFC, Dubai’s international financial centre. I’d spend the day perched at my partner’s kitchen counter, or sprawled in her hammock, writing long-hand into a green notebook. In the evening I would stand at the glass wall, stir-crazy by then, fighting an ice-cream headache brought on by the air conditioning, counting lime-green Lamborghinis crawling nose-to-tail along the six lanes of Al Saada Street, far below.

Once the sun bled out into the mist, I would leave the tower and pick my way over broken and unfinished pavements to the DIFC. There are several ways into the complex; none of them resemble civic space. A narrow, wood-panelled atrium led to the foot of a single, slow escalator. It deposited me on a paved mezzanine from which several huge towers grew. There weren’t any pavements as such, just stretches of empty space between chairs and tables. There were art galleries and offices and a destination restaurant run by a car company, each unit folding into the next, giving me at one moment the feeling of exhilaration, as though this entire place was mine for the taking, the next a sense of tremendous awkwardness as though I’d stumbled uninvited into an important person’s private party.

I couldn’t tell from the outside which mirrored door led to a mall, which to a reception desk, which to a lobby. I would burst into every building with an aggressive confidence, penetrating as far as I could into these indeterminate spaces until I found an exit — though an exit into what, exactly? Another atrium. A bank. A water feature. A beauty salon. Eventually I would be stopped and politely redirected.

*

Of middling years, the space explorer Hal Bregg is having to contend with two kinds of ageing. The first is historical. The other, biological.

He has just returned to Earth after a gap of 127 years, and the place he once called home has turned incomprehensibly strange in the intervening time. Thanks to the dilation effect brought on by interstellar travel, only ten ship-board years have passed. But this interval has been hard on Bregg. The trauma and beauty of his harrowing missions aboard the Prometheus still haunt him, and power some of the Return’s most affecting passages.

Bregg’s arrival on Earth, fresh from acclimatisation sessions on the Moon, is about as exciting as a bus ride. At the terminal there are no parades, no gawkers, no journalists. He’s a curiosity at best, and not even a rare one (there have been other ships, other crews). Arriving at the terminus, he’s just another passenger. He misses the official sent to meet him, decides he’ll find his own way about, sets off for the city, and becomes quickly lost. He can’t find the edge of the terminus. He can’t find the floor he needs. Everything seems to be rising. Is this a giant elevator? “It was hard to rest the eye on anything that was not in motion, because the architecture on all sides appeared to consist in motion along, in change…” He decides to follow the crowd. Is this a hotel? Are these rooms? People are fetching objects from the walls. He does the same. In his hands is a coloured translucent tube, slightly warm. Is this a room key? A map? Food?

“And suddenly I felt like a monkey that has been given a fountain pen or a lighter; for an instant I was seized by a blind rage.”

Among Stanislaw Lem’s many gifts is his understanding of how the future works. The future is not a series of lucky predictions (though Lem was luckier than most at that particular craps table). The future is not wholly exotic; it is, by necessity, still chock full of the past. The future is not one place, governed by one idea. Suppose you get a handle on some major change (Return from the Stars boasts one of those — but we’ll get to “betrization” in a minute). This insight won’t give you some mysterious, magical insight into everything else. You’ll be armed, but you’ll still be lost. The future is bigger than you think.

The point about the future is that it’s unreadable. You recognise the language, but you can no longer speak it. The words fell out of order years ago. The vowels shifted.

“I was numb from the strain of trying not to do anything wrong. This, for four days now. From the very first moment I was invariably behind in everything that went on, and the constant effort to understand the simplest conversation or situation turned that tension into a feeling horribly like despair. ”

Bregg contemplates the horrid beauty of the terminal (yes, he’s still in the terminal. Settle in: he’s going to be wandering that terminal for a very long time) and admires (if that is quite the word) its “coloured galaxies of squares, clusters of spiral lights, glows shimmering above skyscrapers, the streets: a creeping peristalsis with necklaces of light, and over this, in the perpendicular, cauldrons of neon, feather crests and lightning bolts, circles. airplanes, and bottles of flame, red dandelions made of needle-signal lights, momentary suns and haemorrhages of advertising, mechanical and violent.”

But if you think Lem will stop there, in contemplation of an overdriven New York skyline, then you need to read more Lem. The window gutters out. “You have been watching clips from newsreels of the seventies,” the air announces, “in the series Views of the Ancient Capitals.”

*

Science fiction delights in expensive real-estate. Sky-high homes give its protagonists the geostationary perspective they require to scry large amounts of weird information very quickly. In cinema, Rick Deckard and his replicant protege K are both penthouse dwellers. And in J G Ballard’s High Rise (1975) Robert Laing eats roast dog on the balcony of, yes, a 25th-floor apartment.

The world of Return from the Stars is altogether more socially progressive. Its buildings are only partly real, Their continuation is an image, “so that the people living on each level do not feel deprived. Not in any way.” The politics of this future, which teaches its infant children “the principles of tolerance, coexistence, respect for other beliefs and attitudes,” are disconcertingly familiar, and mostly admirable.

But let’s stay with the media for a moment. This is a future adept at immersing its denizens in a thoroughly mediated environment — thus an enhanced movie becomes a “real” in Michael Kandel’s savvy, punning translation. For those who know the canon, there’s a delicious hint here of what’s to come: in Lem’s The Futurological Congress (1971) 29 billion people live out lives of unremitting squalor, yet each thinks they’re a tycoon, wrapt as they are in drug-induced hallucination.

The Return’s future, by contrast, handles the physical world perfectly well, thank you. Its population are not narcotised. Not at all: they’re full of good ideas, hold down rewarding jobs, maintain close friendships, enjoy working marriages, and nurture happy children. They have all manner of things to live for. This future — “a world of tranquility, of gentle manners and customs, easy transitions, undramatic situations” — is anything but a dystopia. Why, it’s not even dull!

*

An operation, “betrization”, conducted in early childhood, renders people incapable of serious violence. Murder becomes literally inconceivable, and as a side-effect, risk loses its allure. Betrization has been universally adopted across the Earth, and it’s mandatory.

Bregg and his ancient fellows cannot help but view betrization with horror. Consequently, no-one has the stomach to force it upon them. This leaves the returning astronauts as predators in fields full of friendly, intelligent, accommodating sheep.

But why would Hal Bregg want to predate? Why would any of them? What would it gain them, beyond a spoiled conscience? Everyone on this contented Earth assumes the returnees are savages, though most are far too polite (or risk-averse) to say so. For Bregg and his fellows, it’s enraging. It’s alienating. It’s a prompt to the sort of misbehaviour that they would otherwise never dream of indulging.

Lem himself considered Return from the Stars a failure, and blamed betrization for it. As an idea, it was too on-the-nose: a melodramatic conceit that he had to keep underplaying so the story — a quiet affair about friendship and love and misunderstanding — would stay on track. But times and customs change, and history has been kind to the Return. It has become, in 2020, a better book than it was in the 1960s. This is because we have grown into the very future it predicted. Indeed, we are embroiled in precisely the kind of cultural conflict Lem said would ensue, once betrization was invented.

“Young people, betrizated, became strangers to their own parents, whose interests they did not share. They abhorred their parents’ bloody tastes. For a quarter of a century is was necessary to have two types of periodicals, books, plays: one for the old generation, one for the new.”

Western readers with experience of university life and politics over the last thirty years will surely recognise themselves in these pages, where timid passions dabble with free love, where thin skins heal in safe spaces, and intellectual gadflies navigate a landscape of extreme emotional delicacy, under constant threat of cancellation.

Will they blush, to see themselves thus reflected? I doubt it. Emulsify them as you like, kindness and a sense of humour do not mix. Anyway, the Return is not a satire, any more than it is a dystopia. It is not, when push comes to shove, a book about a world at all (for which some may read: not science fiction).

It is a book about Hal Bregg. About his impulse towards solitude and his need for company. About his deep respect for old friends, and his earnest desire for new ones. It’s about a kind and thoughtful bull in an emotional china shop, trying desperately not to rape things. It’s about men.

*

We would meet at last and order a cab and within the hour we would be sitting overlooking the Gulf in a bar fashioned to resemble the hollowed interior of a golden nugget. I remember one evening my partner chose what to order and I was handed a glass of a colourless liquid topped with a film of crude oil. I thought: Do I drink this or do I light it? And suddenly I felt like a monkey that has been given a fountain pen or a lighter; for an instant I was seized by a blind rage.

That was the evening she told me why she didn’t want to see me any more. The next day I left for London. 19 March 2017: World Happiness Day. As we turned north for the airport I noticed that the sign at the junction had changed. In place of Al Saada: “Happiness Street.”

And a ten-storey-high yellow smiley icon had been draped across the face of a government building.