Reading Index, A History of the, by Dennis Duncan, for New Scientist, 15 September 2021

Every once in a while a book comes along to remind us that the internet isn’t new. Authors like Siegfried Zielinski and Jussi Parikka write handsomely about their adventures in “media archaeology”, revealing all kinds of arcane delights: the eighteenth-century electrical tele-writing machine of Joseph Mazzolari; Melvil Dewey’s Decimal System of book classification of 1873.

It’s a charming business, to discover the past in this way, but it does have its risks. It’s all too easy to fall into complacency, congratulating the thinkers of past ages for having caught a whiff, a trace, a spark, of our oh-so-shiny present perfection. Paul Otlet builds a media-agnostic City of Knowledge in Brussels in 1919? Lewis Fry Richardson conceives a mathematical Weather Forecasting Factory in 1922? Well, I never!

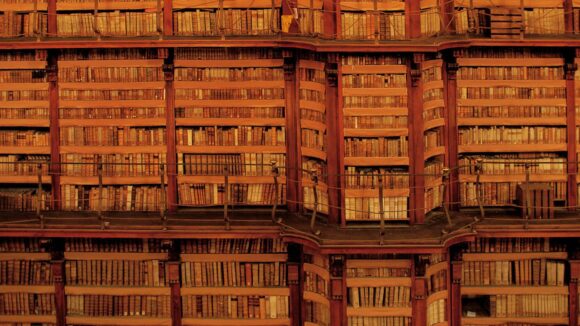

So it’s always welcome when an academic writer — in this case London based English lecturer Dennis Duncan — takes the time and trouble to tell this story straight, beginning at the beginning, ending at the end. Index, A History of the is his story of textual search, told through charming portrayals of some of the most sophisticated minds of their era, from monks and scholars shivering among the cloisters of 13th-century Europe to server-farm administrators sweltering behind the glass walls of Silicon Valley.

It’s about the unspoken and always collegiate rivalry between two kinds of search: the subject index (a humanistic exercise, largely un-automatable, requiring close reading, independent knowledge, imagination, and even wit) and the concordance (an eminently automatable listing of words in a text and their locations).

Hugh of St Cher is the father of the concordance: his list of every word in the bible and its location, begun in 1230, was a miracle of miniaturisation, smaller than a modern paperback. It and its successors were useful, too, for clerics who knew their bibles almost by heart.

But the subject index is a superior guide when the content is unfamiliar, and it’s Robert Grosseteste (born in Suffolk around 1175) who we should thank for turning the medieval distinctio (an associative list of concepts, handy for sermon-builders), into something like a modern back-of-book index.

Reaching the present day, we find that with the arrival of digital search, the concordance is once again ascendant (the search function, Ctl-F, whatever you want to call it, is an automated concordance), while the subject index, and its poorly recompensed makers, are struggling to keep up in an age of reflowable screen text. (Sewing embedded active indexes through a digital text is an excellent idea which, exasperatingly, has yet to catch on.)

Running under this story is a deeper debate, between people who want to access their information quickly, and people (especially authors) who want people to read books from beginning to end.

This argument about how to read has been raging literally for millennia, and with good reason. There is clear sense in Socrates’ argument against reading itself, as recorded in Plato’s Phaedrus (370 BCE): “You have invented an elixir not of memory, but of reminding,” his mythical King Thamus complains. Plato knew a thing or two about the psychology of reading, too: people who just look up what they need “are for the most part ignorant,” says Thamus, “and hard to get along with, since they are not wise, but only appear wise.”

Anyone who spends too many hours a day on social media will recognise that portrait — if they have not already come to resemble it.

Duncan’s arbitration of this argument is a wry one. Scholarship, rather than being timeless and immutable, “is shifting and contingent,” he says, and the questions we ask of our texts “have a lot to do with the tools at our disposal.”