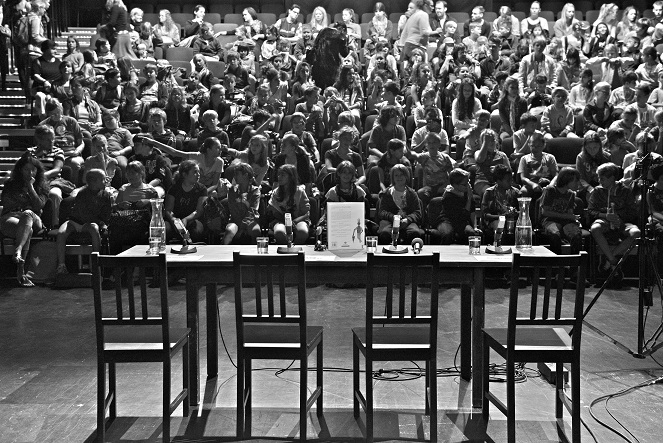

Watching the 2021 European Media Arts Festival on-line for New Scientist, 19 May 2021

For over forty years, the European Media Art Festival in Osnabrueck has offered attendees a glimpse of the best short films coming on-line and to festivals over the coming year. It’s been a reliable cultural barometer, too, revealing, through film, some of our deepest social anxieties and preoccupations. This year saw science fiction swallowing the festival whole.

It’s as though the genre were becoming, not just a valid way to talk about the present, but the only way.

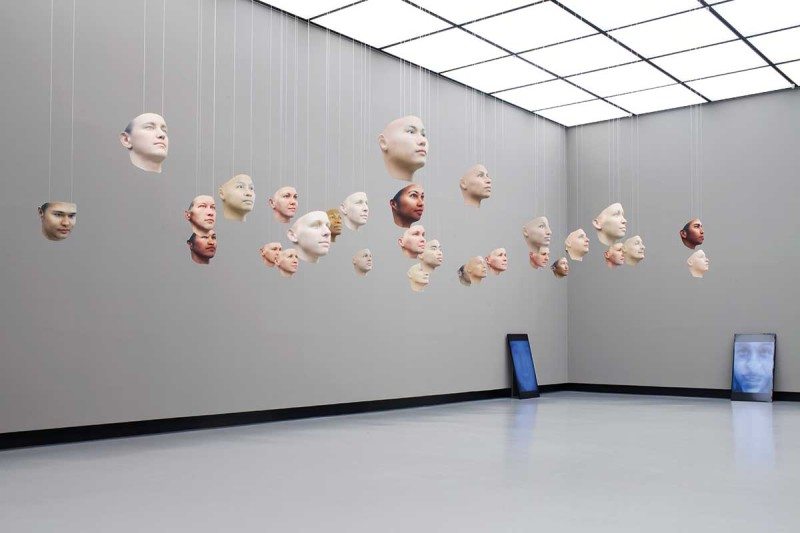

This was the quite explicit message of the audiovisual presentation Planet City and the Return of Global Wilderness by London-trained, LA-based architect Liam Young, much of whose work is speculative — not to say downright science-fictional. Part of Young’s presentation was a retrospective of a career spent exploring global infrastructures, “an unevenly-distributed megastructure that hides in plain sight… slowly stitched together from stolen lands by planetary logistics.”

Forming a powerful contrast with his past travels — through container shipping, the garment supply chain, lithium mining and other real-world adventures — Planet City also featured a utopian future in which humanity sagely withdraws “into one hyper-dense metropolis housing the entire population of the Earth”.

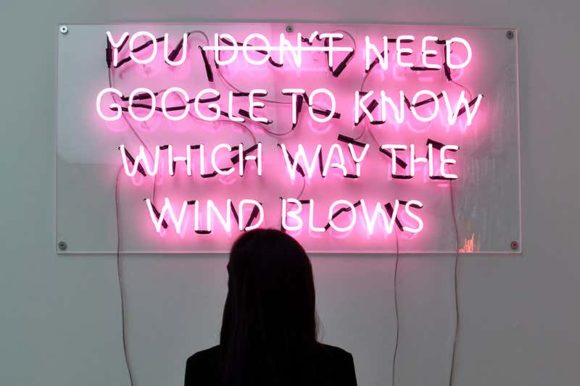

It’s the impossibility of this utopia that’s Young’s point. Science fiction used to be full of such utopian possibilities. These days, however, it has become, Young says, just our favourite way of explaining to ourselves, over and over, the disasters engulfing us and our planet. The once hopeful genre of science fiction cedes ground to dystopia, leaving us “stranded in the long now… waiting for the end of the End of the World”.

We’ve confronted the End of the World before, of course. Marian Mayland’s film essay Michael Ironside and I weaves between three imaginary rooms, assembled from still and short clips from three iconic science fiction films. The rooms are uninhabited, cluttered, uncanny, and cut together to create an imaginary habitation connected to the outside world via shafts and closet doors. War Games’s bedroom in a suburban family house (1983), Real Genius’s California campus dorm room (1985) and the bowels of Sea Quest DSV’s futuristic nuclear submarine (1993) fold into each other to create a poignant fictional 1990s childhood, capturing the effects of Cold War thinking on a generation of geeky male adolescents.

Mayland’s film, which won a German film critics’ award at the festival, is exactly the sort of work — moving between film and performance, document and experiment — that the festival has been championing for over forty years.

Other science-fictional experiments included Josh Weissbach’s A Landscape to be Invented, a collage of wobbly 16mm and Super 8 footage set to excerpts of audiobook sci-fi from the likes of Kim Stanley Robinson and Cixin Liu. It’s a kind of “how to” manual for terraforming a distant world, only this world is not verdant, but violet, not green but purple, as Weissbach passes his footage through a digital, faux-ultraviolet filter.

Zachary Epcar’s more obviously satirical The Canyon sees the calm pace of life in a sunny waterside housing estate turn increasingly strange, as the blissed-out, evesdropped lines of the inhabitants (“Sometimes I come to in the glassware aisle, and I don’t know how I got there”) give way to the meaningless electronic gabble and vibration of phones, toothbrushes and keyfobs.

If this all sounds rather grim, rather unsmiling, even rather hopeless — well, I don’t think the selection, or even the works themselves, were to blame. I think Young is right and the problem lies in science fiction itself: that it’s ceased to be a playground, and has become instead a deadly serious way of explaining increasingly interconnected and technological world. And that’s fine. That’s science fiction growing up.

But what the artist-filmmakers of EMAF have yet to find, is some other way — less technocratic, perhaps, and more political, more spiritual — for imagining a better future.