Reviewing a new verse translation of Gendun Chopel’s Treatise on Passion for The Spectator, 9 June 2018.

The Tibetan artist and poet Gendun Chopel was born in 1903. He was identified as an incarnate lama, and ordained as a Buddhist monk. In 1934 he renounced his vows, quit Tibet for India, learned Sanskrit and — if his long poem, usually translated as A Treatise on Passion, is to be taken at face value — copulated with every woman who let him.

Twelve years later he returned to Tibet, and was thrown into prison on trumped-up charges. The experience broke him. He died of cirrhosis in 1951, as troops of China’s People’s Liberation Army were marching through the streets of Lhasa.

Chopel’s reputation as the most important Tibetan writer of the 20th century is secure, mostly through his travelogue, Grains of Gold. The Passion Book is very different; it is Chopel’s reply to the kamasastra, a classical genre of sanskrit erotica best known to us through one rather tame work, the Kama Sutra.

If Chopel had wanted to show off to his peers back home he could simply have translated the Kama Sutra —but where would have been the fun in that? The former monk spent four years researching and writing his own spectacularly explicit work of Tibetan kamasastra.

It is impossible not to like Chopel — ‘A monastic friend undoing his way of life,/ A narrow-minded poser losing his facade’ — if only for the sincerity of his effort. At one point he tries to get the skinny on female masturbation: ‘Other than scornful laughs and being hit with fists/ I could not find even one who would give an honest answer.’

Still, he gets it: ‘Since naked flesh and sinew are different,’ he warns his (literate, therefore male) readership, ‘How can a thorn sense what the wound feels?’

Thus, like touching an open wound,

The pleasure and pain of women is intense

Chopel insists that women’s and men’s experiences of sex differ, and that women are not mere sources of male pleasure but full partners in the play of passion. So far, so safe. But let’s not be too quick to tidy up Chopel’s long, dizzying, delirious mess of a poem, which jumps from folk wisdom about how to predict a woman’s future by studying the moles on her face, to a jeremiad against the hypocrisy of the rich and powerful, to evocations of tantric states, to the sexual preferences of women in various regions of India, to sexual positions, to fullblown sexual delirium:

They copulate squatting and they copulate standing;

Intertwined, with head and foot reversed, they copulate.

Hanging the woman in the air

With a rope of silk they copulate.

Chopel’s translators, Donald S Lopez Jr. and Thupten Jinpa — Tibetan and Buddhist scholars, who a few years ago also translated Grains of Gold — have appended a long afterword which goes some way to revealing what is going on here.In the Christian faith, sexual intercourse may lead to hell. The early tradition of Buddhism took a different position: sex is fine, so far as it goes; it’s everything that follows — marriage, home, property, domestic contentment, the pram in the hall — that paves the road to perdition.

This is what inspires Buddhism’s tradition of astounding misogyny. Something has got to stop you from having sex with your own wife — and a famous Mahayana sutra has the solution. Think of her as a demon. An ogre. A hag. As sickness, old age, or death:

As a huge wolf, a huge sea monster, and a huge cat; a black snake, a crocodile, and a demon that causes epilepsy; and as swollen, shrivelled and diseased.

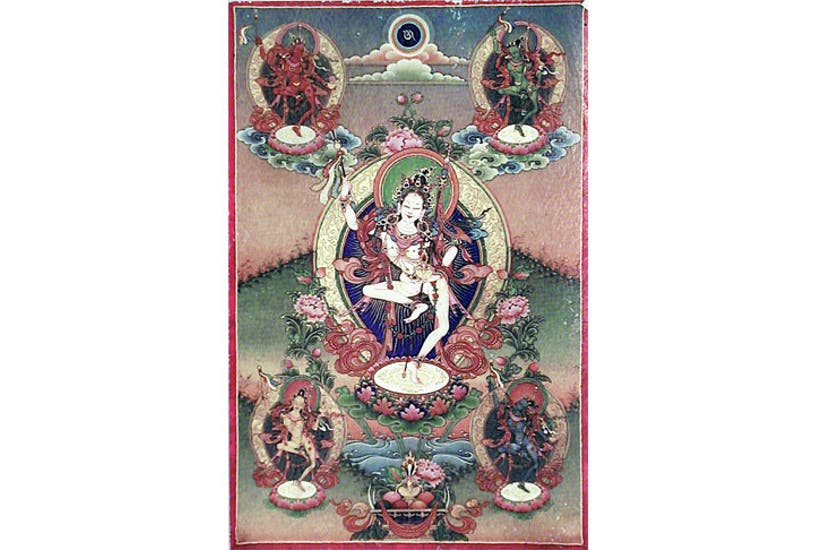

The rise of the tantric tradition altered sexual attitudes to the extent that one was now actually obliged to have intercourse if one ever hoped to achieve buddhahood. But the ideal tantric playmate — a girl of 16 or younger, and ideally low-caste — was still no more than a tool for the enlightenment of an elite male.

Chopel, coming late to the ordinary delights and comforts of sex, was having none of it. Lopez and Jinpa speculate entertainingly about where Chopel sits in the pantheon of such early sexologists as Ellis, Freud and Reich. For sure, he was a believer in sexual liberation: ‘When suitable deeds are prohibited in public,’ he asserts, ‘Unsuitable deeds will be done in private.’

Jeffrey Hopkins translated Chopel’s A Treatise on Passion into prose in 1992 as Tibetan Arts of Love. This is the first effort in verse, and though a clear, scholarly advance, the translators have struggled to render the carefully metered original into lines of even roughly the same number of syllables. You can understand their bind: even in the original Tibetan, there’s still no critical edition. With so much basic scholarship to be done, it would have been pointless if they had simply jazz-handed their way through a loose transliteration.

Their effort captures Chopel’s charm, and that’s the main thing. As Chopel said of the act itself: ‘It may not be a virtue, but how could it be a sin?’