Category Archives: Uncategorized

Too clever by half?

Andrew Robinson‘s study of genius, reviewed for History Today.

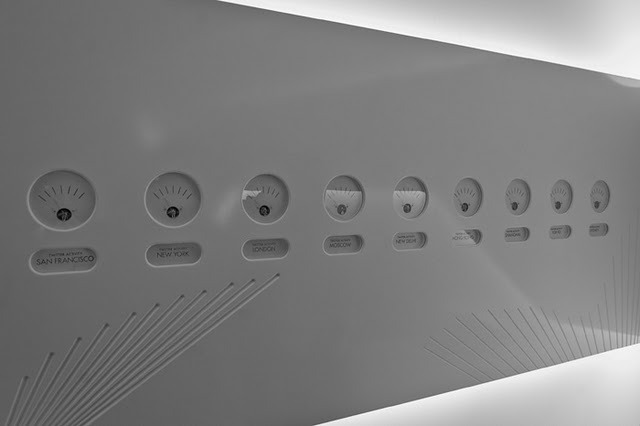

Sobras on the iPhone

Artist-filmmaker Nichola Bruce and digital impresario Will Pearson take my luckless Brazilian footballer for a kick-about in the Cloud. Download the app here.

Histories of science by David Knight and Patricia Fara

reviewed for History Today.

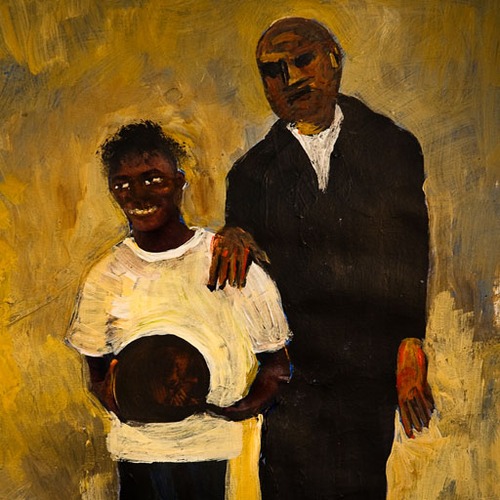

Monkee’s Teeth

Cinematic stories have nothing to do with images. Cinematic stories are to do with silence. In silence, the images unpack themselves. Cinematic stories cannot be mediated. They cannot be told. Tell them, and you hide them. Tell them, and you convey nothing. Worse, you make a fetish of your own presence. Shame on you.

Cinematic stories are lunatic. Their selves have come unhinged.

Untitled

… or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Baroness Greenfield

http://bit.ly/aucOYV

The Lunacy Corporation breaks silence

The Eye: what the reviewers said

Doug Johnstone, The Times, March 10, 2007

Graham Farmelo, Sunday Telegraph, March 24

P D Smith, the Guardian, June 2

Marcus Berkmann, The Spectator, March 31

(requires subscription; the review has been reprinted here)

Gail Vines, the Independent, April 25

Robert Hanks, the Telegraph, March 18

There are fascinating facts galore: our eyes are never still, for example. As well as entertaining, it’s philosophically profound: showing how our eyes, far from simply absorbing the world, are tools with which we construct our own reality.

Katie Owen, the Sunday Telegraph, 27 January 2008

Hermione Buckland-Hoby, the Observer, January 27

Ross Leckie, The Times January 25

Ian Critchley, The Sunday Times, January 27

the Telegraph, February 2

An eye for the eye : Slideshow : Nature News

I prepared this visual presentation for Nature’s Darwin celebrations in 2009

Vision in the womb

http://www.abc.net.au/rn/talks/

8.30/helthrpt/stories/s73272.htm