Next year’s national census may be our last. Opinions are being sought as to whether it makes sense, any longer, for the nation to keep taking its own temperature every ten years. Discussions will begin in 2023. Our betters may conclude that the whole rigmarole is outdated, and that its findings can be gleaned more cheaply and efficiently by other methods.

How the UK’s national census was established, what it achieved, and what it will mean if it’s abandoned, is the subject of The Official History of Britain — a grand title for what is, to be honest, a rather messy book, its facts and figures slathered in weak and irrelevant humour, most of it to do with football, I suppose as an intellectual sugar lump for the proles.

Such condescension is archetypally British; and so too is the gimcrack team assembled to write this book. There is something irresistibly Dad’s Army about the image of David Bradbury, an old hand at the Office of National Statistics, comparing dad jokes with novelist Boris Starling, creator of Messiah’s DCI Red Metcalfe, who was played on the telly by Ken Stott.

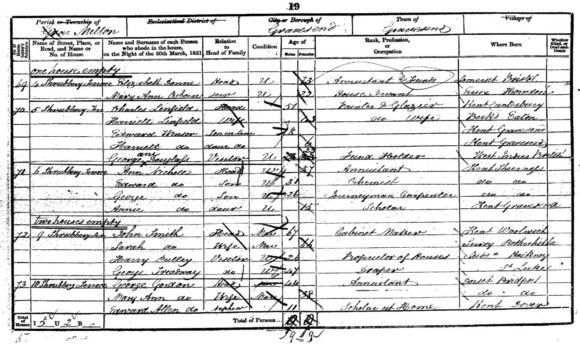

The charm of the whole enterprise is undeniable. Within these pages you will discover, among other tidbits, the difference between critters and spraggers, whitsters and oliver men. Such were the occupations introduced into the Standard Classification of 1881. (Recent additions include YouTuber and dog sitter.) Nostalgia and melancholy come to the fore when the authors say a fond farewell to John and Margaret — names, deeply unfashionable now, that were pretty much compulsory for babies born between 1914 and 1964. But there’s rigour, too; I recommend the author’s highly illuminating analysis of today’s gender pay gap.

Sometimes the authors show us up for the grumpy tabloid zombies we really are. Apparently a sizeable sample of us, quizzed in 2014, opined that 15 per cent of all our girls under sixteen were pregnant. The lack of mathematical nous here is as disheartening as the misanthropy. The actual figure was a still worryingly high 0.5 per cent, or one in 200 girls. A 10-year Teenage Pregnancy Strategy was created to tackle the problem, and the figure for 2018 — 16.8 conceptions per 1000 women aged between 15 and 17 — is the lowest since records began.

This is why census records are important: they inform enlightened and effective government action. The statistician John Rickman said as much in a paper written in 1796, but his campaign for a national census only really caught on two years later, when the clergyman Thomas Malthus scared the living daylights out of everyone with his “Essay on the Principle of Population”. Three years later, ministers rattled by Malthus’s catalogue of checks on the population of primitive societies — war, pestilence, famine, and the rest — peeked through their fingers at the runaway population numbers for 1801.

The population of England then was the same as the population of Greater London now. The population of Scotland was almost exactly the current population of metropolitan Glasgow.

Better to have called it “The Official History of Britons”. Chapter by chapter, the authors lead us (wisely, if not too well) from Birth, through School, into Work and thence down the maw of its near neighbour, Death, reflecting all the while on what a difference two hundred years have made to the character of each life stage.

The character of government has changed, too. Rickman wanted a census because he and his parliamentary colleagues had almost no useful data on the population they were supposed to serve. The job of the ONS now, the writers point out, “is to try to make sure that policymakers and citizens can know at least as much about their populations and economies as the internet behemoths.”

It’s true: a picture of the state of the nation taken every ten years just doesn’t provide the granularity that could be fetched, more cheaply and more efficiently, from other sources: “smaller surveys, Ordnance Survey data, GP registrations, driving licence details…”

But this too is true: near where I live there is a pedestrian crossing. There is a button I can push, to change the lights, to let me cross the road. I know that in daylight hours, the button is a dummy, that the lights are on a timer, set in some central office, to smooth the traffic flow. Still, I press that button. I like that button. I appreciate having my agency acknowledged, even in a notional, fanciful way.

Next year, 2021, I will tell the census who and what I am. It’s my duty as a citizen, and also my right, to answer how I will. If, in 2031, the state decides it does not need to ask me who I am, then my idea of myself as a citizen, notional as it is, fanciful as it is, will be impoverished.