Reading Johann Hari’s Stolen Focus: Why you can’t pay attention for the Telegraph, 2 January 2022

Drop a frog into boiling water, and it will leap from the pot. Drop it into tepid water, brought slowly to the boil, and the frog will happily let itself be cooked to death.

Just because this story is nonsense, doesn’t mean it’s not true — true of people, I mean, and their tendency to acquiesce to poorer conditions, just so long as these conditions are introduced slowly enough. (Remind yourself of this next time you check out your own groceries at the supermarket.)

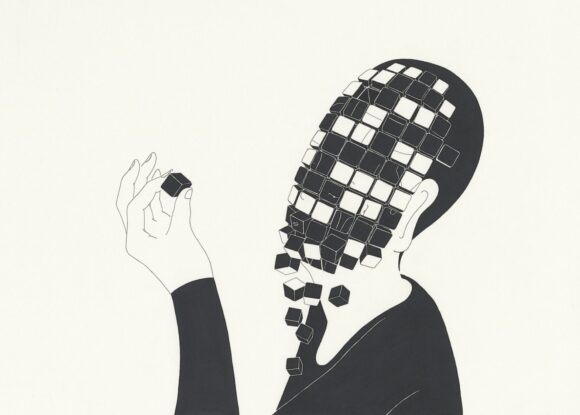

Stolen Focus is about how our environment is set up to fracture our attention. It starts with our inability to set the notifications correctly on our mobile phones, and ends with climate change. Johann Hari thinks a huge number of pressing problems are fundamentally related, and that the human mind is on the receiving end of what amounts to a denial-of-service attack. One of Hari’s many interviewees is Earl Miller from MIT, who talks about “a perfect storm of cognitive degradation, as a result of distraction”; to which Hari adds the following, devastating gloss: “We are becoming less rational less intelligent, less focused.”

To make such a large argument stick, though, Hari must ape the wicked problem he’s addressing: he must bring the reader to a slow boil.

Stolen Focus begins with an extended grumble about how we don’t read as many books as we used to, or buy as many newspapers, and how we are becoming increasingly enslaved to our digital devices. Why we should listen to Hari in particular, admittedly a latecomer to the “smartphones bad, books good” campaign, is not immediately apparent. His account of his own months-long digital detox — idly beachcombing the shores of Provincetown at the northern tip of Cape Cod, War and Peace tucked snugly into his satchel — is positively maddening.

What keeps the reader engaged are the hints (very well justified, it turns out) that Hari is deliberately winding us up.

He knows perfectly well that most of us have more or less lost the right to silence and privacy — that there will be no Cape Cod for you and me, in our financial precarity.

He also knows, from bitter experience, that digital detoxes don’t work. He presents himself as hardly less of a workaholic news-freak than he was before taking off to Massachusetts.

The first half of Stolen Focus got me to sort out my phone’s notification centre, and that’s not nothing; but it is, in the greater scheme of Hari’s project, hardly more than a parody of the by now very familiar “digital diet book” — the sort of book that, as Hari eventually points out, can no more address the problems filling this book than a diet book can address epidemic obesity.

Many of the things we need to do to recover our attention and focus “are so obvious they are banal,” Hari writes: “slow down, do one thing at a time, sleep more… Why can’t we do the obvious things that would improve our attention? What forces are stopping us?”

So, having had his fun with us, Hari begins to sketch in the high sides of the pot in which he finds us being coddled.

The whole of the digital economy is powered by breaks in our attention. The finest minds in the digital business are being paid to create ever-more-addicting experiences. According to former Google engineer Tristan Harris, “we shape more than eleven billion interruptions to people’s lives every day.” Aza Raskin, co-founder of the Center for Humane Technology, calls the big tech companies “the biggest perpetrators of non-mindfulness in the world.”

Social media is particularly insidious, promoting outrage among its users because outrage is wildly more addictive than real news. Social media also promotes loneliness. Why? Because lonely people will self-medicate with still more social media. (That’s why Facebook never tells you which of your friends are nearby and up for a coffee: Facebook can’t make money from that.)

We respond to the anger and fear a digital diet instils with hypervigilance, which wrecks our attention even further and damages our memory to boot. If we have children, we’ll keep them trapped at home “for their own safety”, though our outdoor spaces are safer than they have ever been. And when that carceral upbringing shatters our children’s attention (as it surely will), we stuff them with drugs, treating what is essentially an environmental problem. And on and on.

And on. The problem is not that Stolen Focus is unfocused, but that it is relentless: an unfeasibly well-supported undergraduate rant that swells — as the hands of the clock above the bar turn round and the beers slide down — to encompass virtually every ill on the planet, from rubbish parenting to climate change.

“If the ozone layer was threatened today,” writes Hari, “the scientists warning about it would find themselves being shouted down by bigoted viral stories claiming the threat was all invented by the billionaire George Soros, or that there’s no such thing as the ozone layer anyway, or that the holes were really being made by Jewish space lasers.”

The public campaign Hari wants Stolen Focus to kick-start (there’s an appendix; there’s a weblink; there’s a newsletter) involves, among other things, a citizen’s wage, outdoor play, limits on light pollution, public ownership of social media, changes in the food supply, and a four-day week. I find it hard to disagree with any of it, but at the same time I can’t rid myself of the image of how, spiritually refreshed by War and Peace, consumed in just a few sittings in a Provincetown coffee shop, Hari must (to quote Stephen Leacock) have “flung himself from the room, flung himself upon his horse and rode madly off in all directions”.

If you read just one book about how the modern world is driving us crazy, read this one. But why would you read just one?