Reading The Battle for Your Brain by Nita Farahany for New Scientist, 19 April 2023

Iranian-American ethicist and lawyer Nita Farahany is no stranger to neurological intervention. She has sought relief from her chronic migraines in “triptans, anti-seizure drugs, antidepressants, brain enhancers, and brain diminishers. I’ve had neurotoxins injected into my head, my temples, my neck, and my shoulders; undergone electrical stimulation, transcranial direct current stimulation, MRIs, EEGs, fMRIs, and more.”

Few know better than Farahany what neurotechnology can do for people’s betterment, and this lends weight to her sombre and troubling account of a field whose speed of expansion alone should give us pause.

Companies like Myontec, Athos, Delsys and Noraxon already offer electromyography-generated insights to athletes and sports therapists. Control Bionics sells NeuroNode, a wearable EMG device for patients with degenerative neurological disorders, enabling them to control a computer, tablet, or motorised device. Neurable promises “the mind unlocked” with its “smart headphones for smarter focus.” And that’s before we even turn to the fast-growing interest in implantable devices; Synchron, Blackrock Neurotech and Elon Musk’s Neuralink all have prototypes in advanced stages of development.

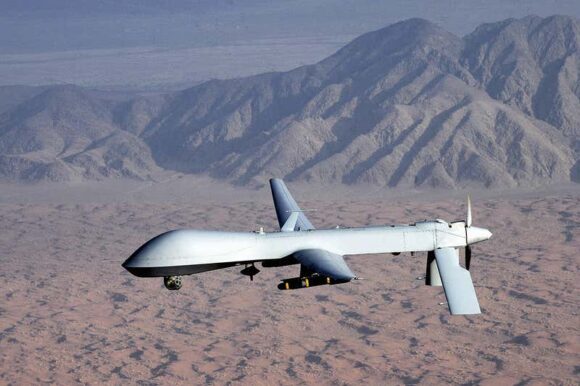

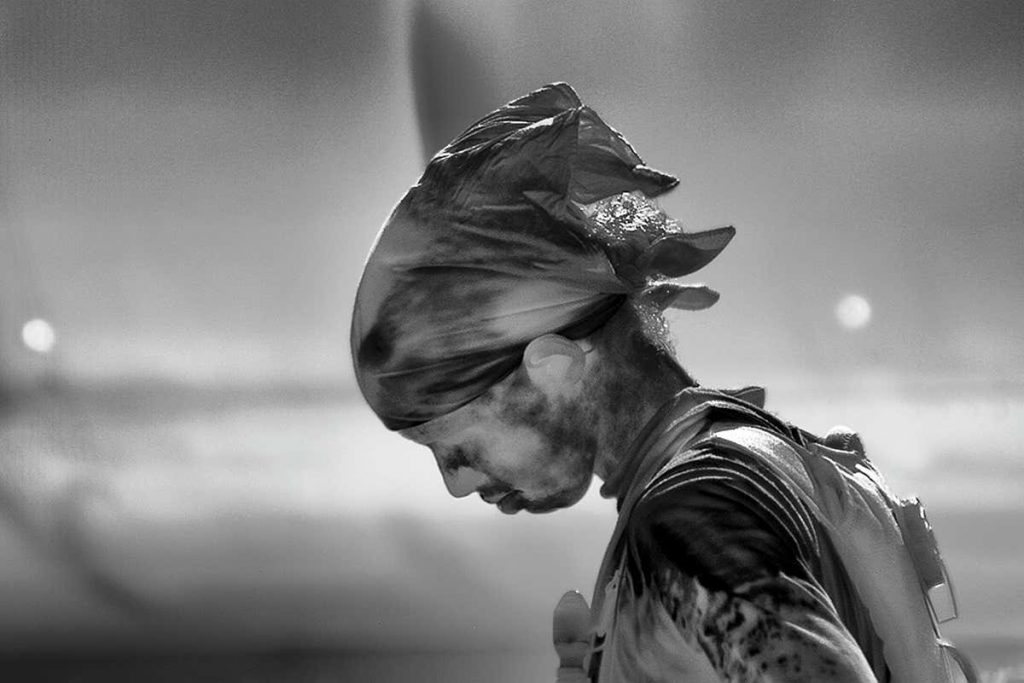

Set aside the legitimate medical applications for a moment; Farahany is concerned that neurotech applications that used to let us play video games, meditate, or improve our focus have opened the way to a future of brain transparency “in which scientists, doctors, governments, and companies may peer into our brains and minds at will.”

Think it can’t be done? Think again. In 2017 A research team led by UC Berkeley computer scientist Dawn Song reported an experiment in which videogamers used a neural interface to control a video game. As they played, the researchers inserted subliminal images into the game and watched for unconscious recognition signals. This game of neurological Battleships netted them one player’s credit card PIN code — and their home address.

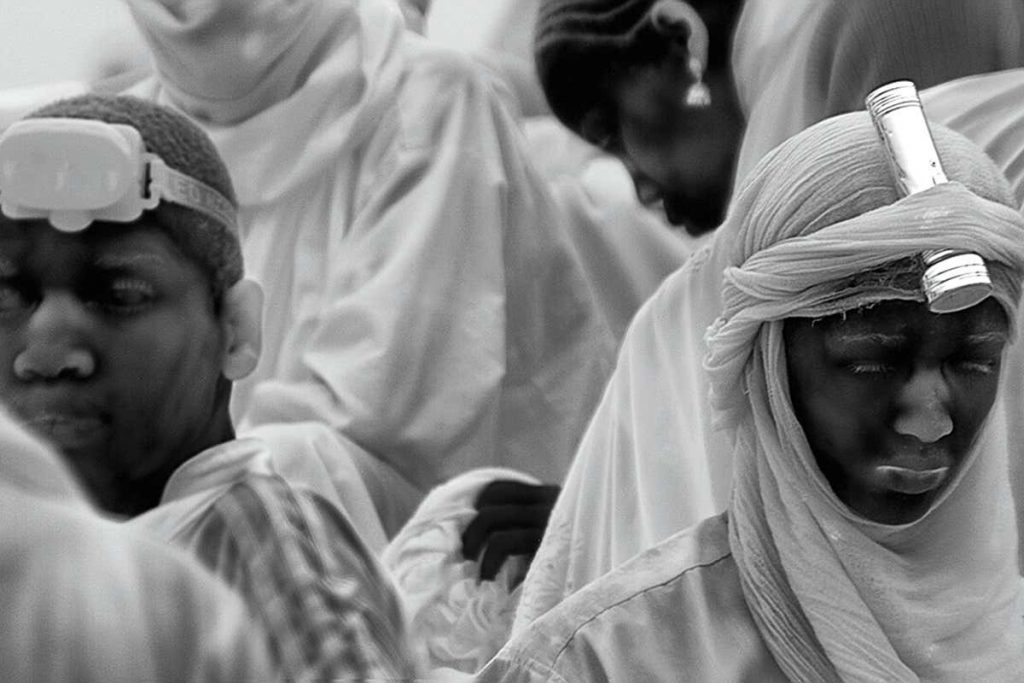

Now Massachusetts-based Brainwave Science is selling a technology called iCognative, which can extract information from people’s brains. At least, suspects are shown pictures related to crimes and cannot help but recognise whatever they happen to recognise. For example, a murder weapon. Emirati authorities have already successfully prosecuted two cases using this technology.

This so-called “brain fingerprinting” technique is as popular with governments (Bangladesh, India, Singapore, Australia) as it is derided by many scientists.

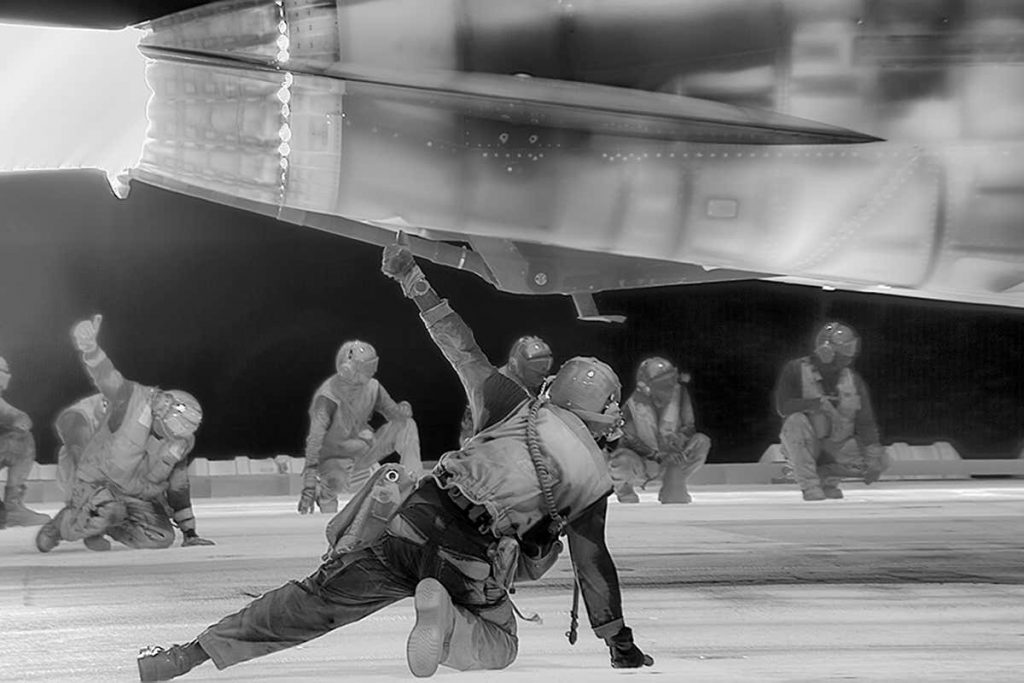

More worrying are the efforts of companies, in the post-Covid era, to use neurotech in their continuing effort to control the home-working environment. So-called “bossware” programmes already take regular screenshots of employees’ work, monitor their keystrokes and web usage, and photograph them at (or not at) their desks. San Francisco bioinformatics company Emotiv now offers to help manage your employees’ attention with its MN8 earbuds. These can indeed be used to listen to music or participate in conference calls — and also, with just two electrodes, one in each ear, they claim to be able to record employees’ emotional and cognitive functions in real time.

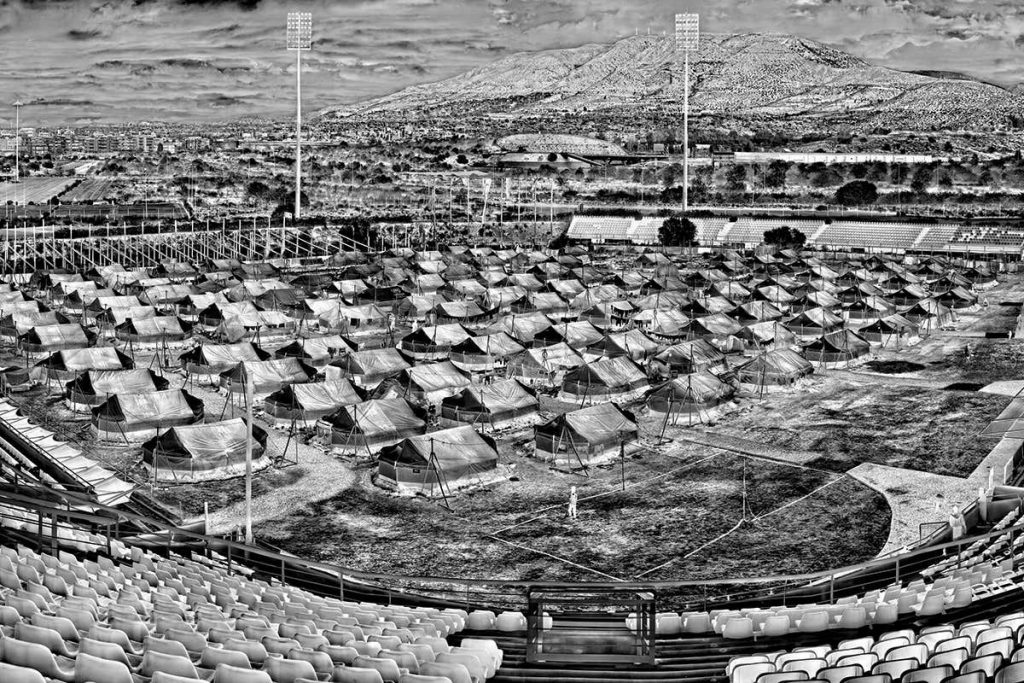

It’ll come as no surprise if neurotech becomes a requirement in modern workplaces: no earbuds, no job. This sort of thing has happened many times already.

“As soon as [factory] workers get used to the new system their pay is cut to the former level,” complained Vladimir Lenin in 1912. “The capitalist attains an enormous profit for the workers toil four times as hard as before and wear down their nerves and muscles four times as fast as before.”

Six years later, he approved funding for a Taylorist research institute. Say what you like about industrial capitalism, its logic is ungainsayable.

Farahany has no quick fixes to offer for this latest technological assault on the mind — “the one place of solace to which we could safely and privately retreat”. Her book left me wondering what to be more afraid of: the devices themselves, or the glee with which powerful institutions seize upon them.