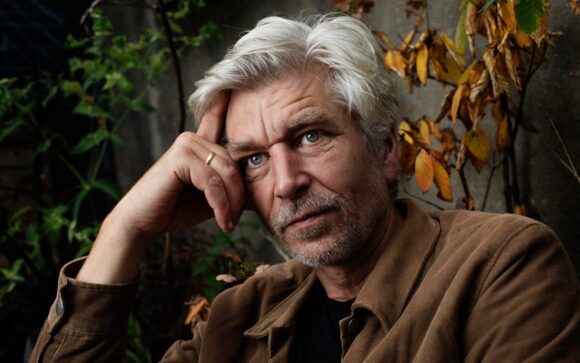

Reading The Wolves of Eternity by Karl Ove Knausgaard for the Telegraph, 12 September 2023

1986: nineteen-year-old Syvert Løyning returns home from navy service to find his widowed mother chain-smoking. If she’s not dying of lung cancer, she’s making a good stab at it. Her declining health leaves Syvert spending most of his evenings looking after his younger brother Joar. His efforts in this direction are sincere but often ineffective.

This is Knausgaard’s long, compelling prequel to 2021’s The Morning Star, a novel which saw time collapse and brought the realms of the living and the dead into collision. To this metaphysical malarkey, The Wolves… offers the unprepared reader the coldest of cold openers. What should we make of Syvert’s slow, ineluctable decline amid the edgelands of southern Norway (woods and heaths and lakes, football fields and filling stations)? What of his equally slow recovery, as he acquires a girlfriend (Lisa), a job (at an undertaker’s) and a purpose — tracking down his dead father’s secret second family in the former Soviet Union?

Half way through, The Wolves… breaks off and moves to present-day [Russia] to follow Syvert’s lost relation Alevtina on her way to her step-dad’s 80th birthday party. Alevtina describes herself self-deprecatingly (and accurately) as “a kind of hippy biologist who talked to trees”. Knausgaard makes a show of giving her the same close attention he devoted to Syvert, but there’s a sight more handwaving going on now: a sophomoric piling-up of cultural capital about Death, Hell and various species of Russian messianism and biophilia. Never trust a protagonist who’s a college lecturer.

Both halves of The Wolves… have their strengths, of course. Alevtina’s half is flashier by far; consider this time-reversed vision of some woods: “If you filmed that, an injured or sick animal that crept away to hide, died and rotted, and then ran that film backwards, the soil would pull apart to become an animal that rose up and slunk away.”

But there’s a greater power, I reckon, to be gleaned in the ordinariness of things. The pity we feel as Syvert sorts out his father’s old boxes, “not to get closer to him, more the opposite, to remove him from me, put him back in his boxes, back with his things”. And terror, when it occurs to Syvert that the World (which The Wolves… sees to its end) is only “what the eyes could see… A sort of duct in front of and behind us, with various things in it. Trees and bushes and hills. Or houses and streets. Or rooms and furniture.”

Knausgaard should resist the siren call of his library card, and go on writing very big books about nothing. The less The Wolves… is about, the more it has to say.