Visiting “Rooted Beings” at Wellcome Collection, London for the Telegraph, 24 March 2022

“Take a moment to draw a cosmic breath with your whole body, slower than any breath you have ever taken in your life.” Over headphones, Eduardo Navarro and philosopher Michael Marder guide my contemplation of Navarro’s drawings, where human figures send roots into the ground and reach with hands-made-leaves into the sky. They’re drawn with charcoal and natural pigments on envelopes containing the seeds of London plane trees. When the exhibition is over, the envelopes will be planted in a rite of burial and rebirth.

What are plants? Garden-centre curios? Magical objects? Medicines? Or trade goods? It’s hard for us to think of plants outside of the uses we put them to, and the five altars of Vegetal Matrix by Chilean artist Patricia Dominguez celebrate (if that is quite the word) their multiple social identities. One shrine contains a medicinal bark, quinine; in another, flowers of toxic Brugmansia, an assassin’s stock-in-trade; In the third sits a mandrake root, carved into the shape of a woman. Dominguez’s artistic research sits at the centre of a section of the exhibition entitled “Colonial violence and indigenous knowledge”.

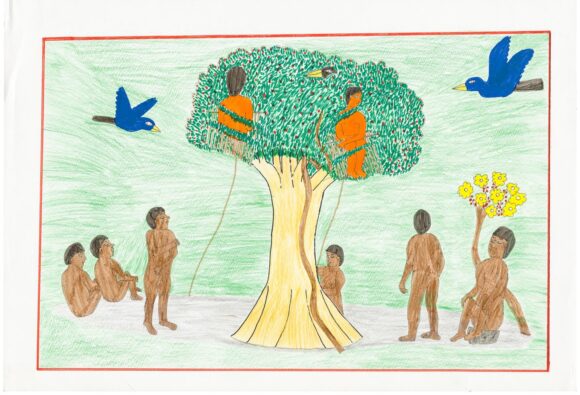

Going by the show’s interpretative material, the narrowly extractive use of plants is a white western idea. But the most exciting exhibits reveal otherwise. From 400 CE there’s a fragment of the world’s earliest surviving herbal, painted on papyrus (we have always admired plants for what we could get out of them). Also from the Wellcome archives, there’s a complex map describing the vegetal “middle realm” of Jain cosmology — obviously a serious effort to establish an intellectual hold on the blooming and buzzing confusion of the plant world. Trees and their associated wildlife are reduced to deceptively simple and captivating shapes in the work on paper of the artist Joseca, whose people, the Yanomami, have been extracting foods and medicines from the Amazon rainforest for generations. His vivid plant portraits are not some classic Linnaean effort at the classification of species, but emotionally they’re not far off. Joseca is establishing categories, not tearing them down.

Bracketing the section about how imperial forces have “appropriated” useful plants (and thank goodness for that! cries the crabbed reviewer, thinking of his stomach as usual) are more introspective spaces. Ingela Ihrman’s enormous Passion Flower costume dominates the first room: time your visit just right, and you will find the artist inhabiting the flower, and may even get to drink her nectar. Not much less playful are the absurdist visions — in textile, embroidery and collage — of Gözde Ilkin, for whom categories (between human and plant, between plant and fungi) exist to be demolished, creating peculiar, and peculiarly endearing vegetal-anthropoid forms.

“Wilderness” is the theme of the final room. There’s real desperation in the RESOLVE Collective’s effort to knap and chisel their way towards a wild relationship with the urban environment. Made of broken masonry and pipework, crates and split paving slabs, this, perhaps, is a glimpse of the Hobbesian wilderness that civilisation keeps at bay.

Nearby, Den 3 is the artist SOP’s wry evocation of the old romantic mistake, cladding misanthropy in the motley of the greenwood. Rather than vegetate on the couch during the Covid-19 pandemic, SOP built a den in nearby woods and there enjoyed a sort of pint-size “Walden Pond” experience — until lockdown relaxed and others began visiting the wood.

At its simplest, Rooted Beings evokes a pleasant fantasy of human-vegetable co-existence. But forget its emolient exterior: at its best this show is deeply uncanny. The gulfs that exist between plant and animal, between species and species, between us and other, serve their own purposes, and attempts to do as Navarro and Marder suggest, and experience the world as a plant might experience it, are as likely to end in horror as in delight. “As you are very slowly dying while also staying alive,” they explain, “your body becomes the soil you are living in.” Crikey.