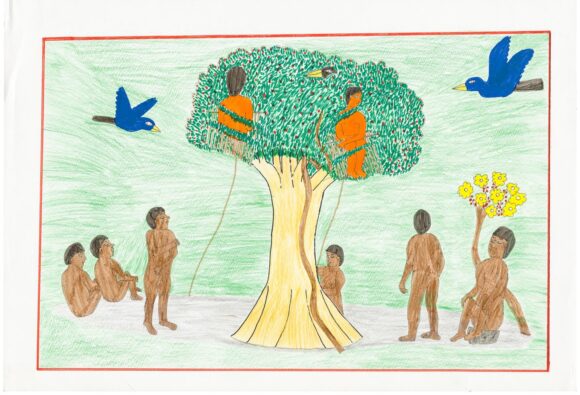

The Edge of Forever, one of four short films by Brighton-based video and installation artist David Blandy, opens with an elegaic pan of Cuckmere Haven in Sussex. A less apocalyptic landscape it would be hard to imagine. Cuckmere is one of the most ravishing spots in the Home Counties. Still, the voiceover insists that we contemplate “a ravaged Earth” and “forgotten peoples” as we watch two children exploring their post-human future. The only sign of former human habitation is a deserted observatory (the former Royal Observatory at Herstmonceux Castle in Sussex). The children enter and study the leavings of dead technologies and abandoned ambitions, steeped all the while in refracted sunlight: Claire Barrett’s elegiac camerawork is superb.

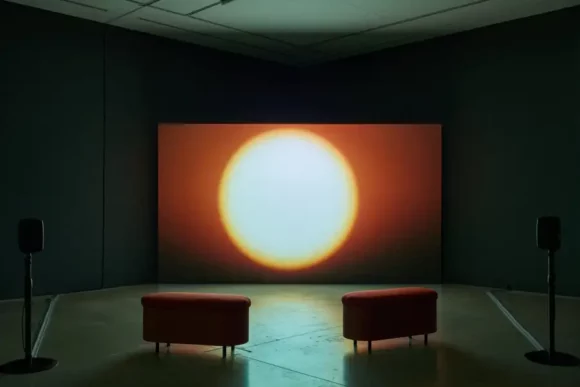

The films in Blandy’s installation “Atomic Light” connect three different kinds of fire: the fire of the sun; the wildfires that break out naturally all over the earth, but which are gathering force and frequency as the Earth’s climate warms; and the atomic blast that consumed the Japanese city of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945.

There’s a personal dimension to all this, beyond Blandy’s vaunted concern for the environment: his grandfather was a prisoner of the Japanese in Singapore during the second World War, and afterwards lived with the knowledge that, had upwards of 100,000 civilians not perished in Hiroshima blast, he almost certainly would not have survived.

Bringing this lot together is a job of work. In Empire of the Swamp

a man wanders through the mangrove swamps at the edge of Singapore, while Blandy reads out a short story by playwright Joel Tan. The enviro-political opinions of a postcolonial crocodile are as good a premise for a short story as any, I suppose, but the film isn’t particularly well integrated with the rest of the show.

Soil, Sinew and Bone, a visually arresting game of digital mirrors composed of rural footage from Screen Archive South East, equates modern agriculture and warfare. That there is an historical connection is undeniable: the chemist Franz Haber received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1918 for his invention of the Haber–Bosch process, a method of synthesising ammonia from nitrogen and hydrogen. That ammonia, a fertiliser, can be used in the manufacture of explosives, is an irony familiar to any GCSE student, though it’s by no means obvious why agriculture should be left morally tainted by it.

Alas, Blandy can’t resist the sirens of overstatement. We eat, he says “while others scratch for existence in the baked earth.” Never mind that since 1970, hunger in the developing world has more than halved, and that China saw its hunger level fall from a quarter of its vast population to less than a tenth by 2016 — all overwhelmingly thanks to Haber-Bosch.

Defenders of the artist’s right to be miserable in face of history will complain that I am taking “Atomic Light” far to literally — to which I would respond that I’m taking it seriously. Bad faith is bad faith whichever way you cut it. If in your voiceover you dub Walt Disney’s Mickey “this mouse of empire”, if you describe some poor soul’s carefully tended English garden as the “pursuit of an unnatural perfection wreathed in poisons”, if you use footage of a children’s tea party to hector your audience about wheat and sugar, and if you cut words and images together to suggest that some jobbing farmer out shooting rabbits was a landowner on the lookout for absconding workers, then you are simply piling straws on the camel’s back.

Thank goodness, then, for Sunspot, Blandy’s fourth, visually much simpler film, that juxtaposes the lives and observations of two real-life solar astronomers, Joseph Hiscox in Los Angeles and Yukiaki Tanaka in Tokyo, who each made drawings of the sun on the day the Hiroshima bomb dropped.

Here’s a salutary and saving reminder that, to make art, you’re best off letting the truth speak for itself.