Reading Saabira Chaudhuri’s Consumed for the Telegraph, 16 May 2025

What happens when you use a material that lasts hundreds of years to make products designed to be used for just a few seconds?

Saabira Chaudhuri is out to tell the story of plastic packaging. The brief sounds narrow enough, but still, Chaudhuri must touch upon a dizzying number of related topics, from the science of polymers to the sociology of marketing.

Consumed is a engaging read, fuelled by countless interviews and field trips. Chaudhuri, a reporter for the Wall Street Journal, brings a critical but never censorious light to bear on the values, ambitions and machinations of (mostly US) businesspeople, regulators, campaigners and occasional oddballs. Medical and environmental concerns are important elements, but hers is primarily a story about people: propelled to unexpected successes, and stymied by unforeseen problems, even as they unwittingly steep the world in chemicals causing untold damage to us all.

Plastic was once seen as the environmental option. With the advent of celluloid snooker balls and combs in the 1860s, who knows how many elephant and tortoise lives were saved? Lighter and stronger than paper (which is far more polluting and resource-intensive than we generally realise), what was not to like about plastic packaging? When McDonald’s rolled out its polystyrene clamshell container across the US in 1975, the company reckoned four billion of the things sitting in landfill was a good thing, since they’d “help aerate the soil”.

The idea was fanciful and self-serving, but not ridiculous, the prevailing assumption then being that landfills worked as giant composters. But landfill waste is not decomposed so much as mummified, so mass and volume count: around half of all landfill is paper, while plastic takes up only a few per cent of the space. This mattered when US landfill seemed in short supply (a crisis that proved fictitious — waste management companies were claiming a shortage so they could jack up their fees.)

The historical (and wrong) assumption that plastics were environmentally inert bolstered a growing post-war enthusiasm for the use-and-discard lifestyle. In November 1963, Lloyd Stouffer, the editor of Modern Plastics magazine, addressed hundreds at a conference in Chicago: ‘The happy day has arrived when nobody any longer considers the plastics package too good to throw away.’

A 2015 YouTube video of a turtle found off the coast of Costa Rica with a plastic straw lodged in his nose highlighted how plastic, so casually disposed of, destroyed the living world, entangling animals, blocking their guts, and rupturing their internal organs.

Rather than abandon disposability, however, manufacturers were looking for ways to make plastics recyclable, or at least compostable, and this is where the trouble really began, and commercial imperatives took a truly Machiavellian turn. Recycling plastic is hard to do, and Chaudhuri traces the ineluctable steps in business logic that reduced much of that effort into nothing more than a giant marketing campaign: what she dubs “a get-out-of-jail-free card in a situation otherwise riddled with reputational risk.”

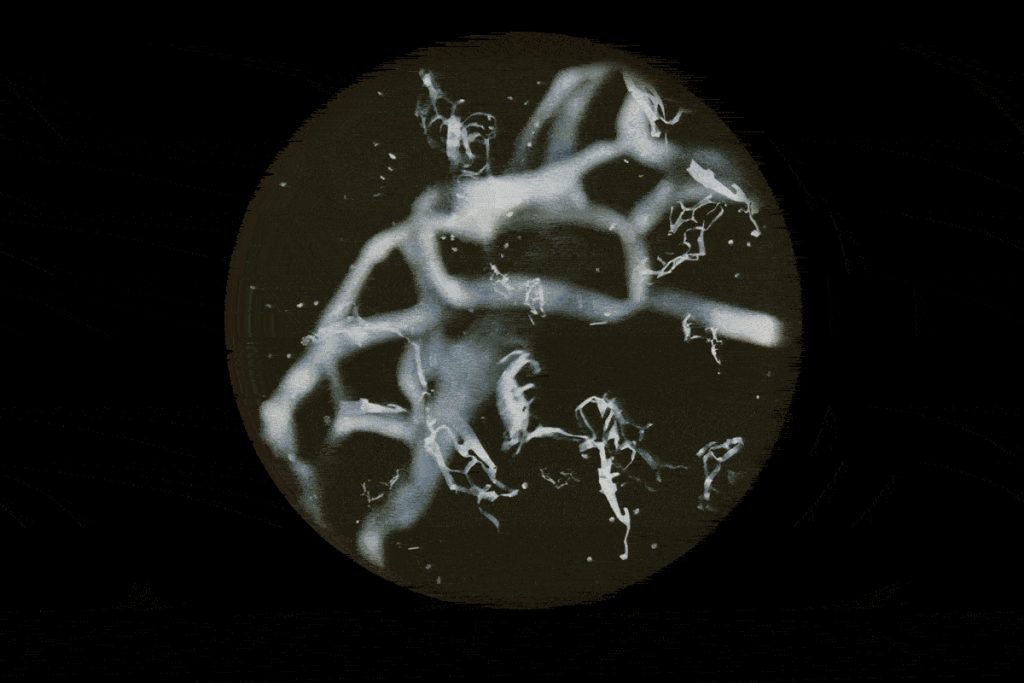

Recycling cannot, in any event, address the latest crisis to hit the industry, and the world. In 2024 the New England Journal of Medicine published an article linking the presence of microplastics to an increased risk of stroke or heart attack, substantiating the suspicion that plastic particles ranging in size from 5,000 micrometres to just 0.001 micrometres, are harmful to health and the environment.

First, they turned up in salt, honey, teabags and beer, but in time, says Chaudhuri, “microplastics were found in human blood, breast milk, placentas, lungs, testes and the brain.”

Then there are the additives that lend a plastic its particular qualities (flexibility, strength, colour and so on); these disrupt endocrine function, contributing to declining fertility in humans — and not just humans — all around the world. The additives transmigrate and degrade in unpredictable ways (not least when being recycled), to the point where no-one has any idea what and how many chemicals we’re exposing ourselves to. How can we protect ourselves against substances we’ve never even seen, never mind studied?

But it’s the humble plastic sachet — developed in India to serve a market underserved by refuse collectors and low on running water — that provides Chaudhuri with her most striking chapter. The sachets are so cheap, they undercut bulk purchases; so tiny, no recycler can ever make a penny gathering them; and so smeared with product, no recycling process could ever handle them.

Chaudhuri’s general conclusions are solid, but it’s engaging business anecdotes like this one that truly terrify.