In Arkady and Boris Strugatsky’s The Beetle in the Anthill, zoopsychologist Lev Abalkin and his alien companion, a sentient canine “bighead” called Puppen-Itrich, are sent to the ruined and polluted planet Hope to find out what happened to its humanoid population. Their search leads them through an abandoned city to a patch of tarmac, which Puppen insists is actually an interdimensional portal. Lev wonders what new world this portal might it lead to?

‘“Another world, another world…” grumbles Puppen. “As soon as you made it to another world, you’d immediately begin to remake it in the image of your own. And your imaginations would again run out of room, and then you’d look for another world, and you’d begin to remake that one, too.”’

Futility sounds like a funny sort of foundation for an enjoyable book, but the Strugatskys wrote a whole series of them, and they amount to a singular triumph. Fresh translations of the final two “Noon universe” books are being published this month.

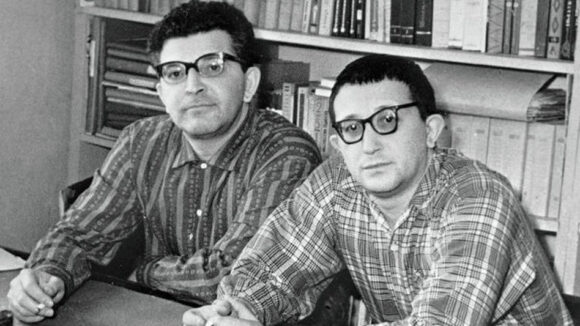

Arkady Strugatsky was born in Batumi, Georgia, in 1925. His kid brother Boris, born in Leningrad in 1933, outlived him by nearly twenty years, though without his elder brother to bounce ideas off, he found little to write about. The brothers dominated Soviet science fiction throughout the 1970s. Their earliest works towed the socialist-realist line and featured cardboard heroes who (to the reader’s secret relief) eventually sacrificed themselves for the good of Humanity. But their interest in people became too much for them, and they ended up writing angst-ridden masterpieces like Roadside Picnic (which everyone knows, because Andrei Tarkovsky’s film Stalker is based on it) and Lame Fate/Ugly Swans (which no-one knows, though Maya Vinokaur’s cracking English translation came out in 2020). Far too prickly to be published in the Soviet Union, their best work circulated in samizdat and (often unauthorised) translation.

The stories and novels of their “Noon universe” series ask what humans and aliens, meeting among the stars, would get up to with each other. Ordinary conflict is out of the question, since spacefaring civilisations have access to infinite resources. (The Noon universe is a techno-anarchist utopia, as is Iain Banks’s Culture, as is Star Trek’s Federation, and all for the same unassailable reason: there’s nothing to stop such a strange and wonderful society from working.)

The Strugatskys assume that there’s one only one really grand point to life as a technically advanced species — and that is to see to the universe’s well-being by nurturing sentience, consciousness, and even happiness.

To which you can almost hear Puppen grumble: Yes, but what sort of consciousness are you talking about? What sort of happiness are you promoting? In The Waves Extinguish the Wind (originally translated into English as The Time Wanderers), as he contemplates the possibility that humans are themselves being “gardened” by a superior race dubbed “Wanderers”, alien-chaser Toivo Glumov complains, “Nobody believes that the Wanderers intend to do us harm. That is indeed extremely unlikely. It’s something else that scares us! We’re afraid that they will come and do good, as they understand it!”’

Human beings and the Wanderers (whose existence can only ever be inferred, never proved) are the only sentient species who bother with outer space, and stick their noses into what’s going on among people other than themselves. And maybe Puppen is right; maybe such cosmic philanthropy boils down, in the end, to nothing more than vanity and overreach.

By the time of these last two novels, the Wanderers’ interference in human affairs is glaring, though it’s still impossible to prove.

In The Beetle in the Anthill Maxim Kammerer — a former adventurer, now a prominent official — is set on the trail of Lev Abalkin, a rogue “progressor” who is heading back to Earth.

Progressors travel from planet to planet and go undercover in “backward” societies to promote their technical and social development. But why shouldn’t Abalkin come home for a bit? He’s spent fifteen years doing a job he never wanted to do, in the remotest outposts, and he’s just about had enough. “Damn it all,” Kammerer complains, “would it really be so surprising if he had finally run out of patience, given up on COMCON and Headquarters, abandoned his military discipline, and come back to Earth to sort things out?”

By degrees, Kammerer and the reader discover why Kammerer’s bosses are so afraid of Abalkin’s return: he may, quite unwittingly, be a “Wanderer” agent.

So an individual’s ordinary hopes and frustrations play out against a vast, unsympathetic realpolitik. This is less science fiction than spy fiction — The Spy Who Came in From the Cold against a cosmic backdrop. And it’s tempting, though reductive, to observe the whole “noon universe” through a Cold War lens. Boris himself says in his afterword to The Beetle…:

“We were writing a tragic tale about the fact that even in a kind, gentle, and just world, the emergence of a secret police force (of any type, form, or style) will inevitably lead to innocent people suffering and dying.”

But the “noon universe” is no bald political parable, and it’s certainly not satire. Rather, it’s an unflinching working-out of what Soviet politics would look like if it did fulfil its promise. It’s a philosophical solvent, stripping away our intellectual vanities — our ideas of manifest destiny, our “outward urge” and all the rest — to expose our terrible littleness, and tremendous courage, in the face of a meaningless universe.

In their final novel The Waves Extinguish the Wind — assembled from fictional documents, reports, letters, transcripts and the like — we follow a somewhat older and wiser Maxim Kammerer as he oversees the heartbreaking efforts of his protogée Toivo Glumov to prove the existence of the Wanderers for once and for all. It’s an odyssey (involving peculiar disappearances, bug-eyed monsters and a bad-tempered wizard) that would be farcical, were it not tearing Glumov’s life to pieces.

Kammerer reckons Glumov is a fanatic. Does it even matter that humans are being tended and “progressed” by some superior race of gardener? “After all,” Kammerer says to his boss, Excellentz, ‘“what’s the worst we can say about the Wanderers?’” He’s thinking back to the planet called Hope, and that strange square of tarmac: ‘“They saved the population of an entire planet! Several billion people!”’

‘“Except they didn’t save the population of the planet,”’ Excellentz points out. ‘“They saved the planet from its population! Very successfully, too… And where the population has gone — that’s not for us to know.”’