Reading The Next 500 Years by Chris Mason for New Scientist, 12 May 2021

Humanity’s long-term prospects don’t look good. If we don’t all kill each other with nuclear weapons, that overdue planet-killing asteroid can’t be too far off; anyway, the Sun itself will (eventually) explode, obliterating all trace of life in our planetary system.

As if awareness of our own mortality hasn’t given us enough to fret about, we are also capable of imagining our own species’ extinction. Once we do that, though, are we not ethically bound to do something about it?

Cornell geneticist Chris Mason thinks so. “Engineering,” he writes, “is humanity’s innate duty, needed to ensure the survival of life.” And not just human life; Mason is out to ensure the cosmic future of all life, including species that are currently extinct.

Mason is not the first to think this way, but he arrives at a fascinating moment in the history of technology, when we may, after all be able to avoid some previously unavoidable catastrophes.

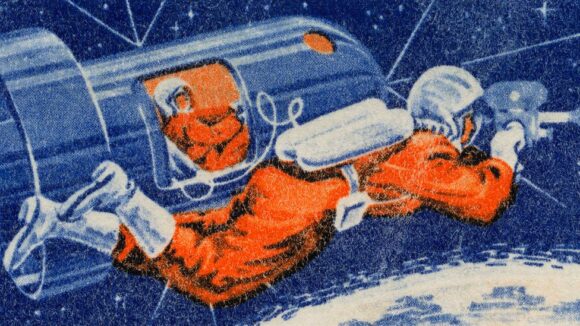

Mason’s 500-year plan for our future involves reengineering human and other genomes so that we can tolerate the (to us) extreme environments of other worlds. Our ultimate goal, Mason says, should be to settle new solar systems.

Spreading humanity to the stars would hedge our bets nicely, only we currently lack the tools to survive the trip, never mind the stay. That’s where Mason comes in. He was principal investigator on NASA’s Twins Study, begun in 2015: a foundational investigation into the health of identical twins Scott Kelly and Mark Kelly during the 340 days Scott was in space and Mark was on Earth.

Mason explains how the Twins Study informed NASA’s burgeoning understanding of the human biome, how a programme once narrowly focused on human genetics now extends to embrace bacteria and viruses, and how new genetic engineering tools like CRISPR and its hopeful successors may enable us to address the risks of spaceflight (exposure to cosmic radiation radiation is considered the most serious) and protect the health of settlers on the Moon, on Mars, and even, one day, on Saturn’s moon Titan.

Outside his specialism, Mason has some fun (a photosythesizing human would need skin flaps the size of two tennis courts — so now you know) then flounders slightly, reaching for familiar narratives to hold his sprawling vision together. More informed readers may start to lose interest in the later chapters. The role of spectroscopy in the detection of exoplanets is certainly relevant, but in a work of this gargantuan scope, I wonder if it needed rehearsing. And will readers of a book like this really need reminding of Frank’s Drake equation (regarding the likelihood of extra-terrestrial civilisations)?

Uneven as it is, Mason’s book is a genuine, timely, and very personable addition to a 1,000-year-old Western tradition, grounded in religious expectations and a quest for transcendence and salvation. Visionaries from Isaac Newton to Joseph Priestley to Russian space pioneer Konstantin Tsiolkowsky have spouted the very tenets that underpin Mason’s account: that the apocalypse is imminent; and that, by increasing human knowledge, we may recover the Paradise we enjoyed before the Flood.

Masonic beliefs follow the same pattern; significantly, many famous NASA astronauts, including John Glenn, Buzz Aldrin and Gordo Cooper, were Freemasons.

Mason puts a new layer of flesh on what have, so far, been some ardent but very sketchy dreams. And, though a proud child of his engineering culture, he is no dupe. He understands and explores all the major risks associated with genetic tinkering, and entertains all the most pertinent counter-arguments. He knows where 19th-century eugenics led. He knows the value of biological and neurological diversity. He’s not Frankenstein. His deepest hope is not that his plans are realised in any recognisable form; but that we continue to make plans, test them and remake them, for the sake of all life.