Watching Nick Lehane: Chimpanzee at Barbican Centre, London

for New Scientist, 20 January 2020

The puppet, a life-sized female chimpanzee, is made out of wood, rope, carved hard foam and paper mâché. She gazes out at the audience from a raised platform and, through movement alone, weaves her tale. When she was young, she lived as part of a human family. Now she is incarcerated in a research laboratory, deprived of company, her mind slowly deteriorating.

Rowan Magee, Andy Manjuck, and Emma Wiseman operate the chimpanzee, the sole actor in a puppet play running at the Barbican Centre in London. The play, Chimpanzee, by Brooklyn-based actor and puppeteer Nick Lehane, is a highlight of 2020’s London International Mime Festival. It is a moving story that is attracting attention from neurologists and cognitive scientists along with the usual performing-arts crowd.

Lehane conceived the show after reading Next of Kin, a memoir by psychologist and primate researcher Roger Fouts. Fouts’s tales of experiments in fostering young chimpanzees in human homes had obvious dramatic potential. Then, as Lehane looked deeper, he discovered a much darker story.

The Fouts family’s own chimps enjoyed a relatively comfortable life once they outgrew their human home. But other chimpanzees in similar programmes found themselves sold to research labs, living out almost inconceivably solitary lives of confinement and vivisection.

Modern efforts to communicate with chimpanzees began in 1967 at the University of Nevada, Reno, when primatologists Allen and Beatrix Gardner set up a project to teach American Sign Language (ASL) to a chimp called Washoe. These experiments have so transformed our view of chimp culture that many of the original researchers are campaigning to end the practice of keeping primates in captivity. (It is still legal to keep primates as pets in the UK.)

Chimpanzee vocalisations aren’t under conscious control, but the apes can communicate using body gestures. “This happens naturally in the wild,” says Mary Lee Jensvold, who advised Nick Lehane on his play. A former student of Roger Fouts, she too campaigns to end primate captivity. “And because chimps live in communities that are relatively closed and quite aggressive with each other, each community has its own repertoire of gestures. Where there’s some overlap, there are differences in how the gestures are articulated.”

In other words, each community speaks in its own accent, and this, says Jensvold, “really speaks to chimpanzees being cultural beings“.

As the sign-language studies grew more ambitious, the Gardners and their colleagues Roger and Deborah Fouts took the chimps into their own homes, acculturating them as humans as far they could to encourage communication.

The obvious question – what is it like growing up in a family that contains chimpanzees? – is the only question Roger Fouts’s son Joshua struggles to answer: “The reality is it’s all I knew.” Joshua, now a media scholar, was raised in a family whose rituals involved members that weren’t human, whose human members would sign to each other so the chimpanzees wouldn’t feel left out of the conversation, and the experience has left him with a profound sense that every non-human has inherent sapience. “When I’m walking down the sidewalk, and I see a human walking with their dog,” he says, “I tend to greet the dog.”

Roger Fouts and his colleagues found that their animals used ASL to communicate with each other, creating phrases by combining signs to denote novel objects.

Washoe was the first chimpanzee to wield ASL in a convincing fashion. Others followed: when Washoe’s mate Moja didn’t know the word for “thermos”, he referred to it as a “metal cup drink”. When Washoe was shown an image of herself in the mirror, and asked what she was seeing, she replied: “Me, Washoe.”

The researchers could hardly credit what they were seeing – and some of their peers still don’t. Jensvold believes there may be a cultural conflict at work. “In the US, comparative psychology has historically been a very lab-based science, where you set up these contrived experiments in order to answer your research questions,” she says. “Out of Europe comes an ethological approach, which is really more about taking the time to observe.”

The sign language research has drawn Jensvold and her colleagues into animal welfare and protection. “We can’t keep doing to them what we’ve been doing,” she says.

Joshua recalls the moment his father reached the same conclusion: “About midway through his career, Roger realised that this was an experiment that should never have been done. Out of the desire to determine what it is about humans that makes us special, we’ve effectively condemned these chimpanzees to a life of incarceration. They’re enculturated to our behaviours. They can never be reintroduced to the wild.”

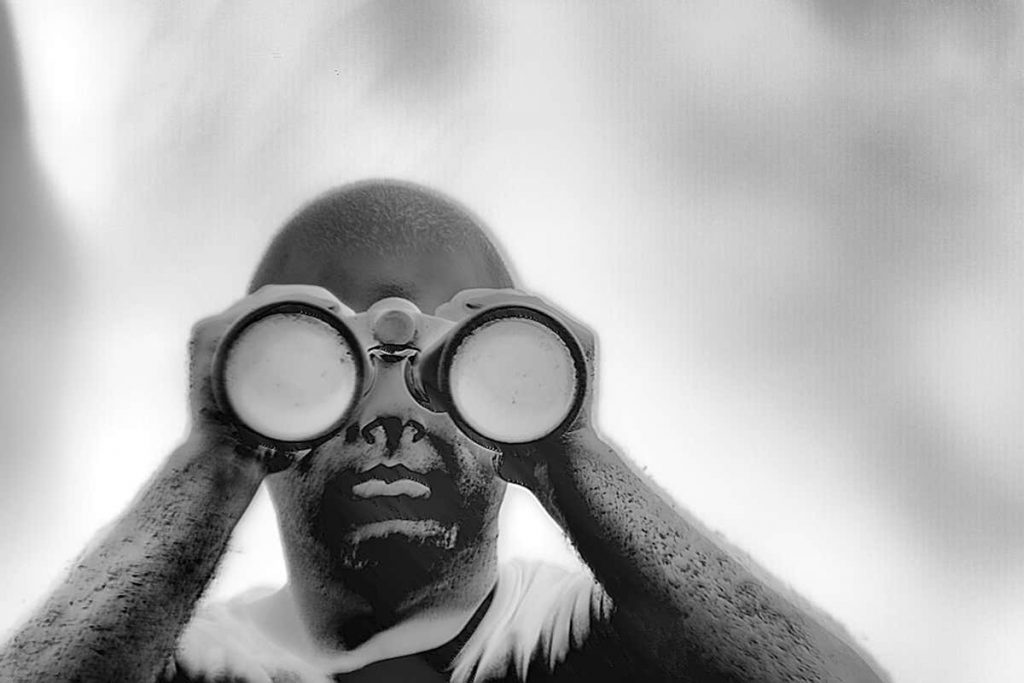

There are no captive chimps in New York, so Nick Lehane’s research for his play consisted almost entirely of watching videos. According to Jensvold, he couldn’t have picked a better form of study. “With video tape,” she says, “you can take close observation down to a minute level.”

By the time Jensvold got involved in Lehane’s project, there was already a performance ready for her to judge. For Lehane, that was a heart-in-mouth moment: “I was afraid that despite our best efforts, we had missed the mark. If anyone was going to think that we had missed something vital about chimp movement or behaviour, it would be Mary Lee.”

He needn’t have worried. “Chimpanzee was phenomenal,” says Jensvold. “I was spotting things that I knew other people in the audience, people who weren’t experts, weren’t going to notice. He captured these incredible nuances.” She pauses: “So the level of suffering that he’s depicting: he gets that right, too.”

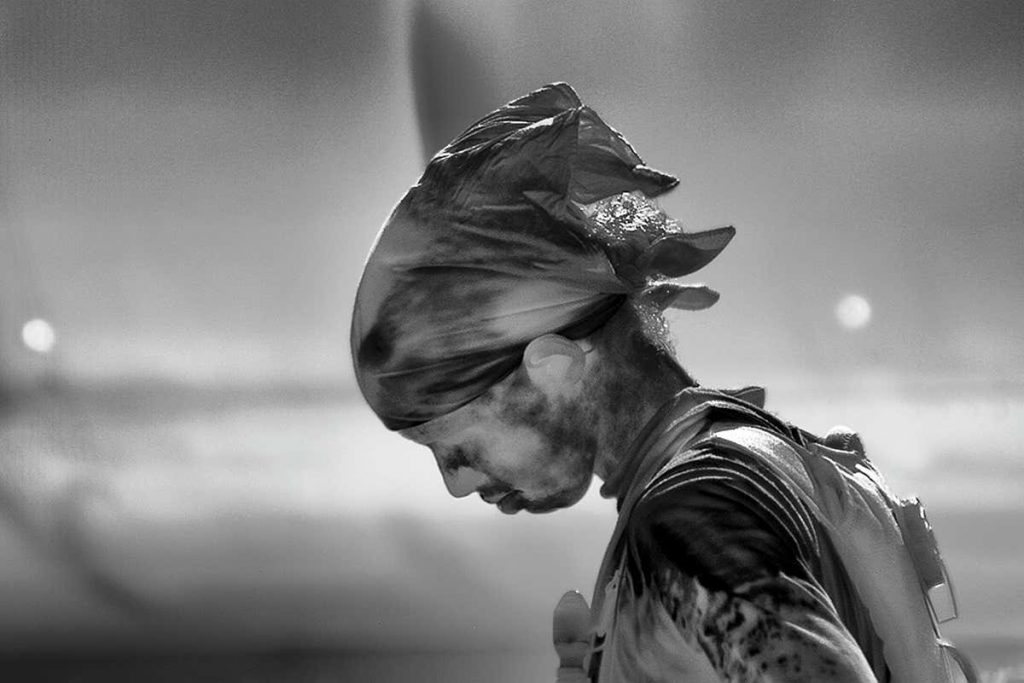

How does Lehane’s chimpanzee convey emotion, given that chimp and human expressions don’t overlap at all precisely?

“A lot of it is in the miming of breath patterns,” says Lehane. “Short little pants and hoots look happy; deep intense heaves and cough will register as a different emotion.”

“One of the things I think is so cool about puppetry is that the audience fills in so many blanks,” he says. “I can’t tell you the number of times that someone has said, ‘How did you make the puppet cry?’ ‘How did you make the puppet frown?’ ‘I loved it when the puppet blinked!’ It tickles me because I just didn’t do any of those things.”

Is there a danger here that the audience is merely anthropomorphising his subject, interpreting his chimpanzee as little more than a funny-shaped human?

In answer, Lehane quotes primatologist Frans de Waal: “To endow animals with human emotions has long been a scientific taboo. But if we do not, we risk missing something fundamental, about both animals and us.”