Baby steps towards an anecdotal history of Russian science…

Sergei Fyodorovich Oldenburg, secretary, Academy of Sciences (1863– 1934)

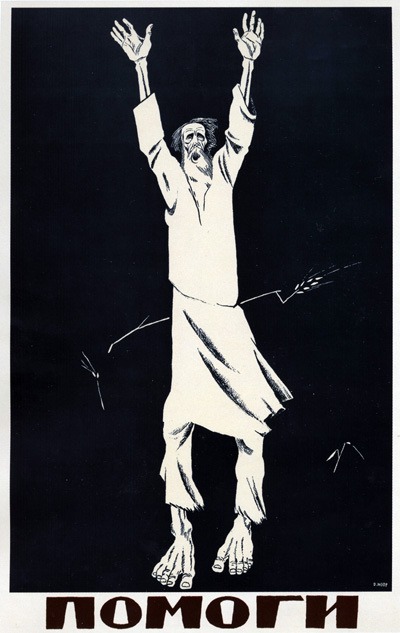

On 13 July 1921, Maxim Gorky appealed to the world for help; less than three months later later, Frank Golder, a native of Odessa with a PhD from Harvard University, found himself steeped in the horrors of the great Russian famine.

Golder had come from Washington to survey the extent of the catastrophe for Herbert Hoover’s American Relief Administration. His reports painted a terrible and complex picture. Russian agriculture had been virtually wiped out by a world war, a revolution, a civil war and then, in 1921, a drought. A government scheme to redistribute food had further alienated Russia’s traditionally suspicious peasant class; many buried and even burned their crops, sooner than hand them over to the Red Army. A survey team member wrote: “There were abandoned homes in the communes by the score, the roofs and wooden parts taken off for fuel, and the walls of mud and straw falling into decay. Everywhere we found emaciated starving children, with stomachs distended from eating melon rinds, cabbage leaves and anything that could be found, things which filled the stomach but did not nourish…”

Arriving in Penza, south-east of Moscow, Golder found the town stricken with cholera and typhus. There were next to no medicines. An 800- bed hospital there had only two thermometers, and the administrator’s best assistant, “thoroughly discouraged”, had committed suicide the day before.

In Moscow, things were better, but even among the reasonably well provided-for members of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 21 had died from disease and malnutrition.

Golder got the impression that Sergei Oldenburg, the Permanent Secretary of the Academy, would soon be joining them. “It is so pitiful and so heart breaking that it completely upsets me,” Golder wrote, recalling his visit for his friend and patron Ephraim D. Adams. “I wish you could meet him for he is one of the most scholarly, cultured and kindly men that I have ever met.” Oldenburg, nearly 60 by then, was bedridden. He was barely able to reach the scraps of toast on his table, let alone chew them. He had spent the past four years trying to support his own family, the orphan children of his brother, his daughter-in-law and his grandchildren, all on about nine million roubles – or five US dollars – a month. The children had bread every day: for the rest of the family, it was a weekly treat.

Sergei Oldenburg was one of the privileged ones: highly-educated, patrician, a personal acquaintance of Vladimir Lenin, and engaged in work vital to the state. Along with other scholars, he had even been recieving a dole, although, as he wrote, “it needed the limitless authority of Lenin and the enormous popularity of Gorky to carry off the issuing of an ‘academic ration’. For this exceptional ration was created before the eyes of the hungry masses who had set themselves the task of destroying all privileges and hierarchies.”

Class resentment, exacerbated by the emergency, was indeed fierce: Frank Golder recalls how one professor called upon the representative of the Crimean government – a young female Communist – to point out that professors in the Crimea were dying of hunger. “What of it?” she had replied. “Let them die!”

Since the October Revolution, Sergei Oldenburg had worked “like a giant” trying to keep up the Academy, trying to find the Academicians something to eat, trying to keep on good terms with the Bolsheviks while striving not to alienate the anti-Bolsheviks. Oldenburg, a world-renowned Orientalist, grandson of a Full General in the Imperial Russian Army, and with a modest amount of blue blood running through his veins, was a liberal nationalist; never a communist. In 1905 he had served in the Russian Provisional Government as Minister of Education. Unlike his political colleagues, however, he had chosen to remain in Russia following the Bolshevik takeover. When Golder, seated at Oldenburg’s bedside in Moscow, talked strenuously about American state recognition, and the good American investment capital might do to save the country, Oldenburg’s mixture of national pride, and his precoccuption with the redemptive powers of suffering, marked him as a leftover of a bygone age:

“Our salvation can not come from without but must come from within and we, as a government and to some extent as a nation have not yet confessed and repented our sins… Let us recover slowly, let us suffer some more the cruel pangs of hunger because it is the only way to get well and strong… All the suffering, all the misery we have endured and are enduring is teaching us Russians to think clearly and that is a great step in the line of progress.”

Oldenburg was certainly a clear thinker: a scholar of Buddhism who welcomed and enjoyed the company of the growing number of Academicians who were natural scientists. The Academy itself was old, founded in 1724 by Peter the Great. It had always been a more reliable friend to the State than the universities, and had enjoyed a privileged position, as a sort of expert arm of the Russian civil service. Oldenburg knew how to convey the Academy’s value to those now in power. He emphasised the practical benefits working with the Academy. His close friend Vladimir Vernadsky had established the Academy’s Commission for the Study of Natural Productive Forces (KEPS) – a key asset in negotiations with the government. Oldenburg asked for money and independence; in return, he could help the State develop greater self-sufficiency in raw materials and manufactures, and even help Lenin with his over-ambitious plan for the rapid electrification of Russia.

It was never an easy compromise, but Lenin, for his part, understood how important the Academy was to the Russia’s survival. (When, in 1922, a Proletkult bigwig wrote a Pravda article hostile to the Academy, Lenin, unimpressed, scrawled in the margin: “And what percentage of [his] loyal proliterians know how to build locomotives?”) So Sergei Oldenburg survived the famine, the flood that inundated his apartment in 1924, and even the attentions of “that black cloud from Moscow”, the astronomer Vartan Ter-Oganezov, an ideologue whose ambitions to remake science in the image of Bolshevism earn him a chapter later in this account. In this chapter, we will see how Oldenburg, with astonishing political dexterity, shaped the future of the world’s largest scientific institution: a sprawling organisation that fed and clothed almost all the people whose lives and and careers are described in this book.

From the beginning, Russian scientists had reservations about communist ideology. Until the “Great Break” and Cultural Revolution of 1929 there was not one member of the Academy of Sciences who was also a member of the Communist Party. But few Academicians could resist the allure of Sergei Oldenburg’s vision of the the Academy’s future: a scientistic programme of modernisation that offered many influential positions to the scientists and engineers willing to work with the communist government. The new Academy grew vast, comprising hundreds of research institutes spread across the USSR. Its central control structure appealed to Lenin’s notorious successor Joseph Stalin. But it appealed just as much to Academicians of Oldenburg’s stripe and generation: men who, in Tsarist times. had argued for nothing else.

Class resentment, wielded as a weapon by Joseph Stalin, eventually destroyed the arrangements Oldenburg spent so many years maintaining. Oldenburg was dismissed from his post during the “Great Break” of 1929. His legacy lived on, nonetheless: a collosal working institution, often troubled, often compromised, but recognised the world over as a pillar of world science.