Past Simon Parkin’s account of the siege of Leningrad, and the fate there of the world’s first proper seed bank, past his postscript and his afterword, there are eight pages which — for people who know this story already — will be worth the rest of the book combined.

It’s the staff roll-call, meticulously assembled from Institute records and other sources, of what Parkin calls simply the Plant Institute. That is, more fully, the Leningrad hub of the Bureau of Applied Botany, the Vsesoyuzny Institut Rastenievodstva, founded in the nineteenth century by German horticulturalist and botanist Eduard August von Regel and vastly expanded by Russian Soviet agronomist Nikolai Vavilov.

It does not make for easy reading.

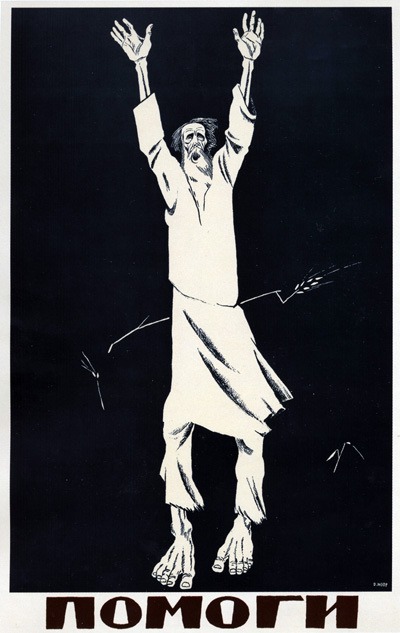

“Starvation… starvation… starvation… died at front…” Between 8 September 1941 and 27 January 1944, while German forces besieged the city, the staff of the Institute in St Isaac’s Square sacrificed themselves, one by one, to protect a collection whose whole raison d’être<OK?Good! SI] was to one day save humanity from starvation.

While, just around the corner, Leningrad’s Hermitage art museum’s two million artefacts were squirreled away for safety, the Plant Institute faced problems of a different order. Its 2,500 species — hundreds of thousands of seeds, rhizomes and tubers — were alive and needed to be kept a degree or two above freezing. And among those, 380,000 examples of potato, rye and other crops would only survive if planted annually. This in a city that was being shelled for up to eighteen hours at a time and where the temperature could — and in February 1942, did — fall to around -40degC.

Iogan Eikhfeld, the institute’s director following Vavilov’s disappearance (his arrest and secret imprisonment, in fact), was evacuated to the town of Krasnoufimsk in the Ural mountains. A train containing a large part of the collection was to follow<OK? Yes SI], but never made it. Eikhfeld eventually got word to the Institute, begging his staff to eat the collection and save themselves. But they had lost the collection to hunger once before, in the dreadful winter of 1921-1922; they weren’t going to again.

January and February 1942 were the worst months. In the dark, freezing building of the Institute, workers prepared seeds for long-term preservation. They divided the collection into several duplicate parts, while bombs burst around them.

The Germans never did succeed in overrunning Leningrad. The rats did. That first winter, hordes of vermin swarmed the building. No effort to protect the collection proved rat-proof: they’d break into the ventilated metal boxes to devour the seeds. Still, of the Institute’s quarter of a million accessions, only 40,000 were consumed by vermin or failed to germinate.

The collection survived, after a fashion. The plantsman and Stalinist poster-child Trofim Lysenko — Vavilov’s inveterate opponent — maintained that the whole enterprise was disordered and for a long time, until the 1970s, it was allowed to deteriorate.

Contributions from abroad helped sustain it. It once received potatoes from the Tucaman University in Argentina, thanks to a chance meeting between its director Peter Zhukovsky and a German plant collector, Heinz Brücher. [It turned out that Brücher had been an officer in the SS Nazi paramilitary group in the late 1990s, Slightly garbled here. “In the 1990s it emerged that during the war, Brücher had been an officer” etc. etc.] leading a special commando unit charged with raiding Soviet agricultural experimental stations. So Brücher hadn’t really been donating valuable varieties of potato after all: he had been returning them.

The fortunes of war

The Forbidden Garden of Leningrad is a generous and desperately sad account of human generosity and sacrifice. If it falls short anywhere, it’s at exactly the place Parkin himself identifies. In this city laid to waste, among the bodies of the fallen, the frozen — in some hideous cases, the half-eaten — starving people make for rotten witnesses of their own condition. The author only had scraps to go on <OK? Good! SI].

And, you can’t research and produce at the pace Parkin does without some loss of finesse; his last book, The Island of Extraordinary Captives, about the plight of foreign nationals interned by the British on the Isle of Man, only came out in 2022. Parkin can tend to turn incidental details into emblems of things he hasn’t got time to discuss. The passing mention that Vavilov’s calloused hands are “an intimate sign of his deep and enduring connection to the earth”, for example, leaves the reader wanting more <OK? Good SI].

Sensation will carry your account so far, and Parkin’s horrors are few and carefully chosen. “Some ate joiner’s glue,” he writes, “made from the bones and hooves of slaughtered animals, just about edible when boiled with bay leaves and mixed with vinegar and mustard.” A nurse is arrested “on suspicion of scavenging amputated limbs from the operating room”. At the Institute, biochemist Nikolai Rodionovich Ivanov prepares some raw-hide harnesses, “cut into tagliatelle-like strips and boiled for eight hours”, for a dinner party.

But hunger hollows out more than the belly. Soon enough, it hollows out the personality. In the relatively few interviews Parkin was able to source, he tells us, survivors from the Institute “spoke in broadly emotionless terms of how the moral, mortal dilemma they faced was, in fact, no dilemma at all”. Their argument was that, in the end, purpose sustained them better than a few extra calories. Vadim Stepanovich Lekhnovich, curator of the tuber collection, can speak for all here: “It was impossible to eat up [the collection], for what was involved was the cause of your life, the cause of your comrades’ lives.”

Parkin applies skill and intelligence to the (rather thankless) business of recasting familiar stories in a fresh light and has a reputation for winkling out obscure but important episodes of wartime history. It is reasonable, then, that he should cut to the chase and condense the science. Two 2008 books on Vavilov’s arrest amidst scientific disagreements with Lysenko do a better job on that front <OK? Good SI]: Peter Pringle’s The Murder of Nikolai Vavilov and Gary Paul Nabhan’s brilliant though boringly titled Where Our Food Comes From. For example, Parkin dubs Lysenko’s theories of developmental plasticity an “outlier theory”, even though it wasn’t. Vavilov had wanted translated into English an Institute report that contained a surprisingly positive chapter about Lysenko’s ideas.

Parkin does get the complicated relationship between the two agronomists <OK? Yes SI], though. What perhaps caused the most friction between the two biologists was Lysenko’s ineptitude as an experimentalist. Parkin, to his credit, nails the human and political context with a few adept and well-timed asides.

And he broadens his account to depict what, to a modern audience is a very strange world indeed — a pre-‘green revolution’ world in which even the richest nations lived under the threat of starvation, even in times of peace; and a world which, when it went to war, wielded famine as a weapon.

The Forbidden Garden of Leningrad is a greatly enjoyable book. Parkin’s chief accomplishment, though, has been to unshackle an important story from its many and complex ties to botany, genetics and developmental science, and lend it a real edge of human desperation.