Visiting the Transmediale festival in Berlin for New Scientist, 21 February 2018

BERLIN’S festival of art and media culture Transmediale is an annual reminder that art is more than a luxury good. It gives us the words, images and ideas we need to talk to each other about a changing world.

Big social changes involve big shifts in how art is made and consumed. It is a nerve-racking process for artists, who can have no idea, as they embark on their ventures, whether the public will come to appreciate and enjoy their work. And at this year’s Transmediale, the chickens came home to roost.

To begin at the beginning, back in the 1950s, Andy Warhol and the pop art movement looked at the world through the prism of advertising hoardings and television. A new generation of artists has been making art out of the internet.

Some artists have attempted to imagine the internet itself, paying attention to developments in data management and artificial intelligence, so they can better imagine what the internet is and what it might become.

The performance premiering at the festival this year, James Ferraro’s Dante-esquePlague, was work of this sort: a credible, visceral and downright terrifying portrayal of consciousness emerging from the audio-visual detritus of social media.

Other artists have used the internet as a tool through which to look at the world. Much of this work resembles anthropology more than art. Take Lisa Rave’s film Europium, which flits between trading floors, TV showrooms and a wedding ceremony in Papua New Guinea to trace the material connections and cultural gulfs that distinguish different kinds of money, from seashell dowries to plastic banknotes. In so doing, she constructs a microhistory of the rare element europium that wouldn’t look out of place in a high-end magazine, and brings the hackneyed link between capitalism and colonialism to life.

But there is a problem: artists working with the materials of the internet are further removed from physical reality than their forebears. They are looking at the world through what is, really, a single, totalising, bureaucratic machine. (It’s called the World Wide Web for a reason.) And in art, as in life, you are what you eat.

The internet sorts. It archives. Many of its artists are, in consequence, good little bureaucrats who offer “findings”, “research” and “presentations” (at Transmediale we even had an “actualisation”, from artist and gay activist Zach Blas), but rarely anything as trite as finished work.

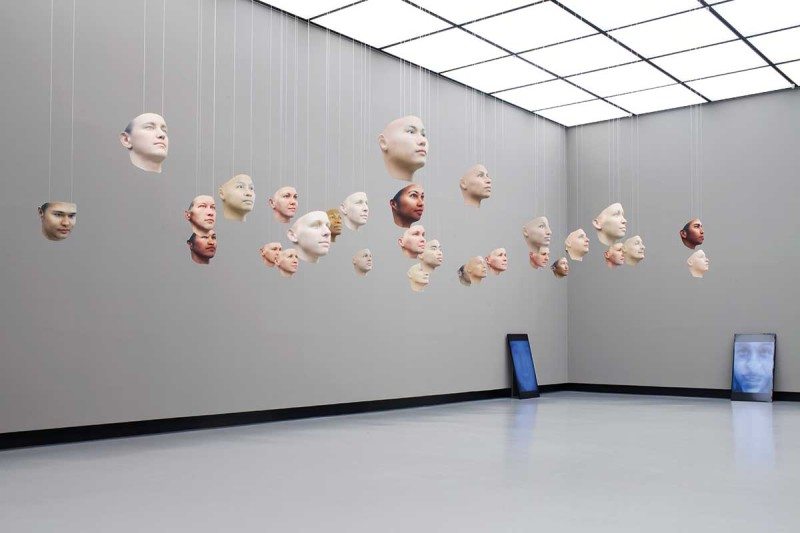

Nothing ages on the internet; nothing dies. Nothing is ever resolved. Similarly with its art: Heather Dewey-Hagborg’s A Becoming Resemblance, which uses DNA from Chelsea Manning, the former US soldier who leaked classified documents, is to all intents and purposes a brand new piece, but it is still presented as a fragment of a work begun in 2015.

Does the open-endedness of this art make it bad? Of course not. But internet art hardly ever gets finished. There’s always more data to sort, a virtual infinitude of rabbit holes to hurl yourself down, and very little that is genuinely new has had a chance to emerge. I defy a newcomer to tell the difference between the work premiering here and work that is 20 years old.

The field has, as a consequence, turned into the art world’s Peter Pan: the child that never grew up. And we treat it as a child. We tiptoe around anything resembling a negative opinion, as though every time one of us said, “I don’t believe this piece is any good”, a video artist somewhere would fall down dead.

In other words, the world of media art has suffered the same fate that has befallen the rest of the internet-enabled planet. The very technology that promised us the world on a screen has been steadily filtering out the challenges and contrary opinions that made our interests and ideas so vital in the first place, leaving us living in an echo chamber.

It was Lioudmila Voropai, a Ukrainian art historian, who got the gathered artists, curators and academics at Transmediale to confront some chilly realities about their field. We knew the book she was launching contained dynamite because it was entitled Media Art as a By-Product – no punches pulled there. Another reason was that she spent all her time telling us what her book didn’t do. It didn’t criticise. It didn’t take a political position. It asked a few questions. It didn’t have answers. Nothing to see here.

Finally someone piped up: “So the media art we’ve come here to enjoy and talk about and theorise over actually exists only to sustain museums of media art? Is that what you’re saying?”

And Voropai, perhaps figuring that she may as well be hung for a sheep as a lamb, let rip: “The extraordinary thing about media art,” she said, “is that the moment it was institutionally established, it was declared conceptually obsolete.”

This was only the beginning. Speaker after speaker made sincere efforts to get the left-wing, countercultural, transgressive Transmediale participants to look at themselves in the mirror. It took courage to try to get media artists to admit that their radical chic has been stolen by the likes of the just-as-countercultural far-right Breitbart News Network; that they have forgotten (as right-wingers like Donald Trump have not) how to entertain; and that they exist chiefly to sustain the institutions that fund them. These efforts were received with seriousness and courtesy.

Attempts to puncture the “new media art” bubble from the inside might have seemed a bit laughable to outsiders. Occupying most of the venue’s impressive foyer, Hate Library was a printout of the results (pictured left) artist Nick Thurston obtained when he typed “truth” into the search box on the online bulletin board of the white-supremacist Stormfront Europe group. The idea, I think, was to confront the Transmediale crowd with the big, bad world outside. But to the rest of us, this felt like old news. If you go there, and type that, surely you get what you deserve?

Even so, I am inclined to admire people who take their social and artistic responsibilities seriously enough to ask uncomfortable questions of themselves, and risk a bit of awkwardness and ridicule along the way.

After all, much of this work does get under your skin. It does make you look at the world anew. As I was leaving, I looked in at Yuri Pattison’s installation Vitra Alcove (some border thoughts). Pattison has mashed up videogame-generated coastal cities and garbled news tickers to capture the queasy liquidity of mediated life.

Sitting there, bombarded by algorithmically generated fake news and dizzy from the image blizzard, I was reminded of the few fraught days I once spent sitting among New Scientist‘s news team as it fished for real stories in a web-borne ocean of alarmism, self-promotion and misinterpretation. Pattison’s work says at least as much about my life as L. S. Lowry’s paintings of matchstalk men and cats and dogs said about my grandfather’s.

In January 2015, Eric Schmidt, then executive chairman of Google, declared that the internet was destined to disappear. He was talking about the internet of things: how the infrastructure that is beginning to weave together the materials and objects of daily life would burrow its way into our lives, and so become invisible.

But if, in the act of becoming ubiquitous, the internet also disappears, then our lives will be held hostage by a bureaucratic infrastructure we can no longer see, never mind control. Media art explores and shines strong light onto this complacent, hyper-conformist, not-so-brave world. Of course the art is strange, hard to explain – and a work in progress. How could it not be? That is its job.