Watching iHuman dircted by Tonje Hessen Schei for New Scientist, 6 January 2021

In 2010 she made Play Again, exploring digital media addiction among children. In 2014 she won awards for Drone, about the CIA’s secret role in drone warfare.

Now, with iHuman, Tonje Schei, a Norwegian documentary maker who has won numerous awards for her explorations of humans, machines and the environment, tackles — well, what, exactly? iHuman is a weird, portmanteau diatribe against computation — specifically, that branch of it that allows machines to learn about learning. Artificial general intelligence, in other words.

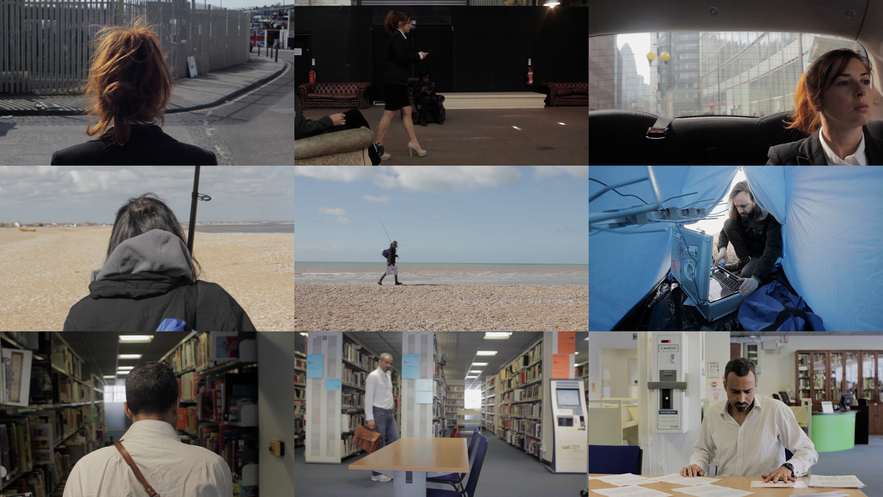

Incisive in parts, often overzealous, and wholly lacking in scepticism, iHuman is an apocalyptic vision of humanity already in thrall to the thinking machine, put together from intellectual celebrity soundbites, and illustrated with a lot of upside-down drone footage and digital mirror effects, so that the whole film resembles nothing so much as a particularly lengthy and drug-fuelled opening credits sequence to the crime drama Bosch.

That’s not to say that Schei is necessarily wrong, or that our Faustian tinkering hasn’t doomed us to a regimented future as a kind of especially sentient cattle. The film opens with that quotation from Stephen Hawking, about how “Success in creating AI might be the biggest success in human history. Unfortunately, it might also be the last.” If that statement seems rather heated to you, go visit Xinjiang, China, where a population of 13 million Turkic Muslims (Uyghurs and others) are living under AI surveillance and predictive policing.

Not are the film’s speculations particularly wrong-headed. It’s hard, for example, to fault the line of reasoning that leads Robert Work, former US under-secretary of defense, to fear autonomous killing machines, since “an authoritarian regime will have less problem delegating authority to a machine to make lethal decisions.”

iHuman’s great strength is its commitment to the bleak idea that it only takes one bad actor to weaponise artificial general intelligence before everyone else has to follow suit in their own defence, killing, spying and brainwashing whole populations as they go.

The great weakness of iHuman lies in its attempt to throw everything into the argument: :social media addiction, prejudice bubbles, election manipulation, deep fakes, automation of cognitive tasks, facial recognition, social credit scores, autonomous killing machines….

Of all the threats Schei identifies, the one conspicuously missing is hype. For instance, we still await convincing evidence that Cambrdige Analytica’s social media snake oil can influence the outcome of elections. And researchers still cannot replicate psychologist Michal Kosinski’s claim that his algorithms can determine a person’s sexuality and even their political leanings from their physiology.

Much of the current furore around AI looks jolly small and silly one you remember that the major funding model for AI development is advertising. Most every millennial claim about how our feelings and opinions can be shaped by social media is a retread of claims made in the 1910s for the billboard and the radio. All new media are terrifyingly powerful. And all new media age very quickly indeed.

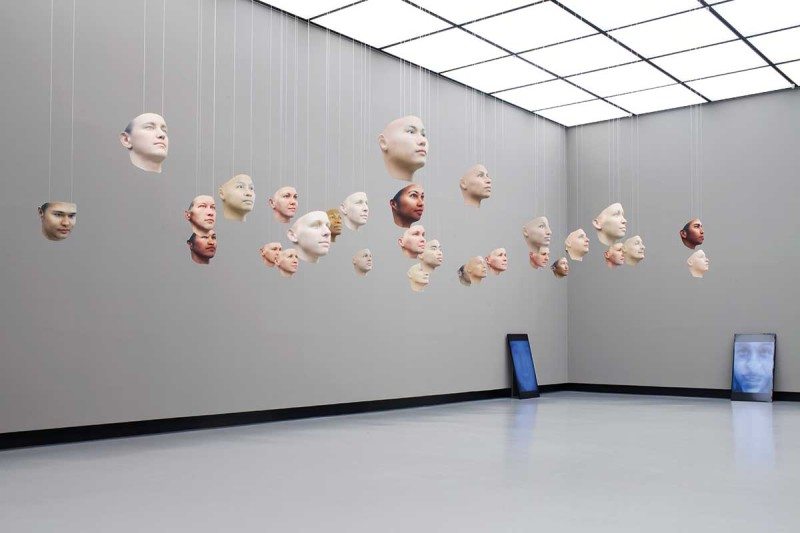

So there I was hiding behind the sofa and watching iHuman between slitted fingers (the score is terrifying, and artist Theodor Groeneboom’s animations of what the internet sees when it looks in the mirror is the stuff of nightmares) when it occurred to me to look up the word “fetish”. To refresh your memory, a fetish is an inanimate object worshipped for its supposed magical powers or because it is considered to be inhabited by a spirit.

iHuman’s is a profoundly fetishistic film, worshipping at the altar of a God it has itself manufactured, and never more unctiously as when it lingers on the athletic form of AI guru Jürgen Schmidhuber (never trust a man in white Levis) as he complacently imagines a post-human future. Nowhere is there mention of the work being done to normalise, domesticate, and defang our latest creations.

How can we possibly stand up to our new robot overlords?

Try politics, would be my humble suggestion.